You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

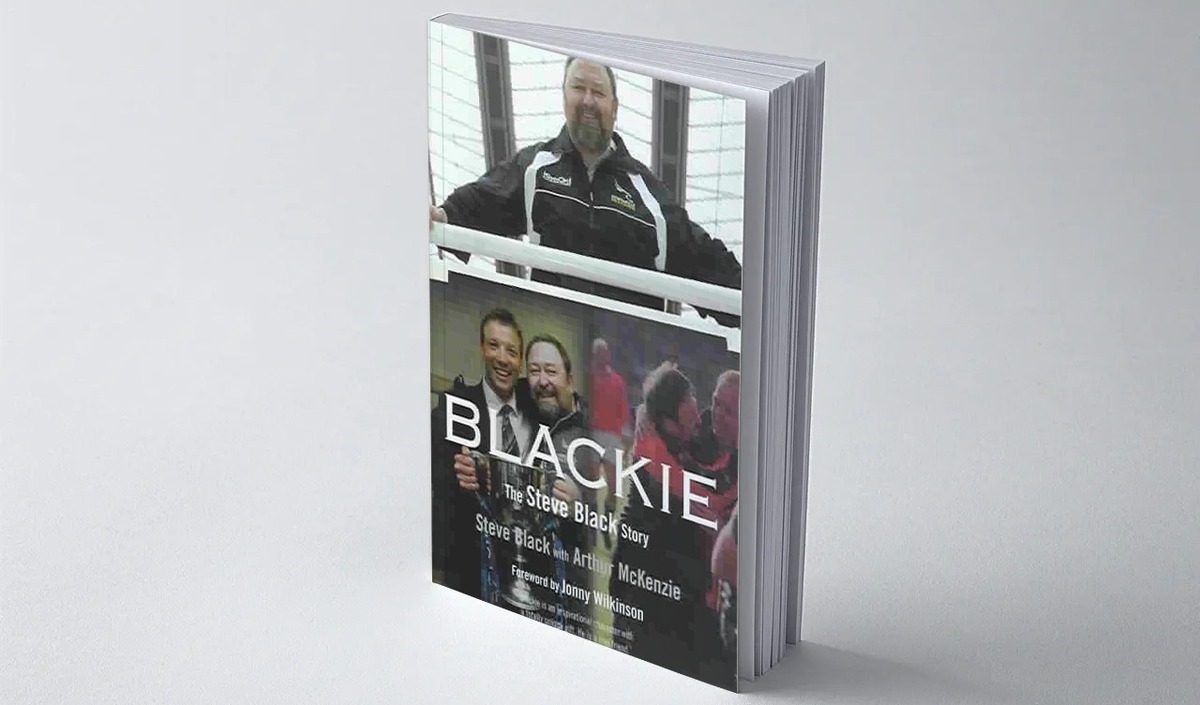

Black magic

If you want proof of the benefits from a “softer” approach to coaching look no further than Steve Black. Achieving success with Newcastle Falcons, Wales and the British Lions in rugby and Newcastle United, Sunderland and Fulham in football, Black won praise as a coach from Kevin Keegan, Rob Andrew, Graham Henry and many other senior sporting figures.

Players and coaches are quoted throughout this book insisting that Black is special. For Jonny Wilkinson he is “an inspirational character with a totally unique gift.” So what lies behind the church-going former nightclub bouncer and what can others learn from him?

Black had a working class background in Newcastle. He father left home when he was young and he became the man of the house. His first love was football, but he was volatile and had a short fuse, getting sent off regularly for retaliation. He was “a complete and utter raving lunatic” according to a childhood friend.

With an interest in boxing and developing a reputation for handling himself well, he became a club doorman, who could stop a fight by saying “That’s enough! Don’t spoil my night”. However, demonstrating a more cerebral side to his nature, Black was at the same time going to day-release college and night school classes in business, accountancy and law. He took an Open University degree in art history, but remained a revered hard man on Tyneside – often asked to sort out violent disputes even after he had given up bouncing, got married and had children.

Black says he was never charged, arrested or in any trouble with the police. Some say he has something of an aura about him. He says his bouncing experiences taught him many coaching skills – organising a team, dealing with owners and directors, helping set codes of behaviour, and presumably, knowing how to gain respect from people.

Black was coaching at an early age, almost instinctively, he says. He was running fitness classes in his teens. His work developing individuals drew him to the attention of Kevin Keegan who was looking to build a new backroom team to reinvigorate a struggling Newcastle United.

Word of his accomplishments spread, and by 1994 he was also working at Sunderland football club. From 1995 to 1998 he was training Newcastle, Sunderland and the Newcastle Falcons at the same time. “He jumped out of the pack as a motivator,” said Rob Andrew, the former director of rugby at Newcastle.

Physical conditioning, as in fitness, accounts for only around 15 per cent of his work, says Black. The rest is an extremely demanding and complex role involving preparing the team physiologically and psychologically for competition. “Aerobics teacher, psychologist, psychiatrist or priest. I see myself as all of these.”

Black’s special approach was to take conditioning to a much higher level. He takes a time-consuming individual, and personal approach to coaching. “You’ve got to love the players, Graham” he told Henry during his time at Wales, and Henry concedes in his autobiography that Black was the perfect complement to his own technical, perhaps rather mechanical approach.

Black brought individual attention to players and a passion sometimes lacking in management. He made it his business to get to know players and find out how they tick. Each player would be given interim goals, then a final objective considering the player’s natural abilities in attaining those goals. “Every individual is unique. Some require more emotional and spiritual support, yet only a modicum of time on the physical. The combination is endless,” says Black.

So while Black was the individual mentor, the coach with the quiet word to the downhearted, out of form player, he was also the rabble-rousing cheerleader before a match, delivering high octane team talks with no holds barred, to wind up the players and bring out their aggression. It was a powerful mixture.

Black’s experience in his school football team personifies the twin approaches that can be taken to coaching a winning team. He was influenced by an encouraging coach and on the one hand insists: “I still believe that most people respond better to a kind word than a kick up the backside.” However, he also concedes that when a new coach with a “tough approach” took over the team it probably helped focus him on his sporting competitiveness.

Above all, Black appears to have brought a down-to-earth approach to conditioning, using humour as an effective tool to bond players, defuse stressful situations and relieve tension, and plain common sense, when he simply advised that players would perform better if they were not trained so hard.

The “specialness” identified by so many of those who worked with him was that he would do the opposite of mainstream opinion if he believed it to be true.

Published in 2004, this is a chatty and readable book, interspersed with comments written by friends, acquaintances and sporting colleagues. It reads like one imagines Black speaks and is thankfully free of blow-by-blow accounts of matches found in so many other sporting biographies. Black professes his Christian faith but does not dwell on the subject, apart from mentioning that instead of joining the team for the night before meal, he preferred to spend some time alone in church.

Back then he ominously predicted “the current world champion England rugby team need to further individualise their preparatory programmes if England are to have a chance of retaining their number one status.”

It was with the Welsh national team that perhaps Black’s skills were put to work with the greatest success. Henry had sought him out at Newcastle Falcons as being instrumental in making the club a significant force in newly professional rugby. When they met in 1998, they immediately agreed that all sessions should be high tempo, and that their content should be readily transferrable to the field.

In the Welsh job, he abolished conventional fitness testing, lowered the volume of training and increased the intensity. This was intended to give players more energy during games (because their legs wouldn’t be so heavy from doing so much training).

This combined with Henry’s tactical acumen and confident demeanour creating a winning team. In the first game under Henry, Wales narrowly lost to South Africa, having previously been beaten by the Springboks by more than 100 points.

It was a mixed start, but Wales then went on to win 11 games in a row, the run only ending in the quarter final of the 1999 World Cup against the eventual winners, Australia. Henry summed up Black’s approach with the quote: “Blackie is the most positive man in the world.”

Black resigned from Welsh national rugby team, disillusioned partly by “the Welsh media-promoted lack of self-esteem within the rugby environment. He moved to Fulham Football Club, but only lasted five months, leaving out of loyalty to the sacked manager Paul Bracewell.

He returned to the Falcons and was then called upon again by Henry to help the British and Irish Lions 2001 tour of Australia. His experience was disappointing, not that he didn’t have an effect, but that he found it hard to operate in such a highly charged political environment. There were disagreements about who were the best coaches, strains between Welsh and English players, and conflicts over the volume of training. The squad landed at 1am jet-lagged, and began training at 7.30am the same day, something Black disagreed with.

Coaches wanting to adopt the Blackie approach should be warned that it is hard, time-consuming work. “The only reasons for not training everyone slightly differently in their chosen sport of activity are the constraints of time or laziness on the part of their coach or trainer.”

Before a game Black wrote individual handwritten notes to all players personally delivered before a game, including the substitute and other squad members. They might contain comments about the forthcoming match or the previous day’s training. They might point out how well he is doing or just small personal observations to help. “I tried to learn as much as possible about each player, their birthdays, families and such details, because this gave me an important personal approach. I saw as my main function as setting an environment for everyone,” said Black.

His other insights provide hope for those who support coaching technique as more important than professional game experience. “Coaching, whether it be football or any other sport, is much the same. People make the mistake of coaching sports instead of people,” he said.

It will be perhaps of little surprise to the rugby fraternity that Black believes rugby players are “tougher, more intelligent and more capable of being empowered than footballers”.

He believes school teachers have a profound influence over young people, and thinks football clubs should do more to take responsibility for educating players about behaviour.

Having suffered with his health, Black is now a motivational speaker.

Blackie - The Steve Black Story

Mainstream Publishing 240pp

Editor's Picks

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Pressing principles

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Defensive organisation

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Related

Unlocking the wing backs

Building the attack and third player runs

Play around to play through

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

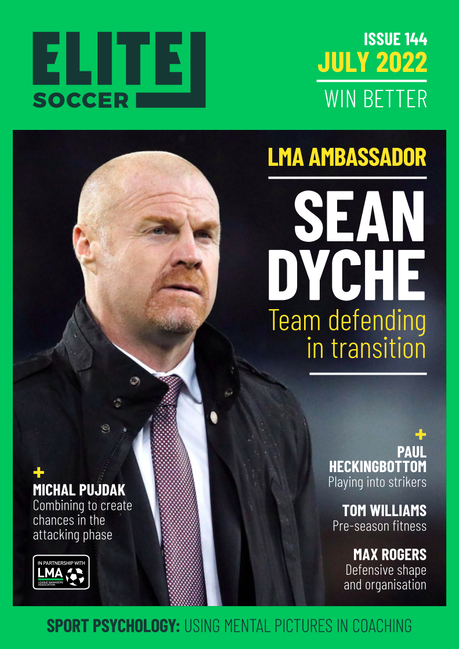

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.