You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Chapter and verse

Why are certain individuals successful and others not? What makes them special and what are they like as people?

The myth about those who succeed, according to Malcolm Gladwell in Outliers, is that they are born in modest circumstances and pretty much, through talent alone, fight their way to the top.

In fact, he argues, they usually have many additional advantages, cultural legacies and opportunities, and above all, the benefit of good timing. All these factors mean success is less about individuals and more about conditions, leading Gladwell to conclude that with society organised slightly differently, success could be attainable by more people. The world would be a better place.

Outliers contains persuasively argued examples from business, music and sport. Bill Gates was a keen computing student just at the beginning of the IT revolution but also was fortunate enough to get privileged access to one of the first major computers. The advantage this gave him to get programming hours under his belt set him way ahead of others in the field and was the launch pad for the creation of the giant software company Microsoft that made him a billionaire.

The Beatles, accomplished songwriters, became superb performers only through their extraordinary experience in Hamburg where they sometimes had to play for up to eight hours at a time. In seven years they played 1,200 times live – more than many modern bands would play in an entire career. Their success may have been guaranteed but would they have been so big without being a great live act?

There is something unusual about professional Canadian ice hockey players - not their height or the colour of their hair, but the fact they are most likely to have been born in the first half of the year. In fact, in any group of elite Canadian ice hockey players, 40 per cent will have been born between January and March, 30 per cent between April and June, 20 per cent between July and September and 10 per cent between October and December. Why?

Perhaps rather obviously, in Canada the eligibility cut-off for age-class hockey is January 1. So some players can be almost a year older than others when talent is being identified and selected. Representative teams are chosen early – at age nine or 10 – and those selected as ‘talented’ are likely to be the larger and more coordinated players, who simply benefit from extra months of maturity.

Once chosen, those players get the benefits of playing more games against better opponents, better coaching – and at least twice as much practice.

“If you make a decision about who is good and who is not good at an early age; if you separate the ‘talented’ from the ‘untalented’; and if you provide the ‘talented’ with superior experience, then you’re going to end up giving a huge advantage to that small group of people born closest to the cut-off date.”

Gladwell notes that this phenomenon is evident in many sports where players are selected, streamed and differentiated. In England the eligibility date is September 1, and in the Premier League at one point during the 1990s, there were 288 players born between September and November compared to only 136 arriving between June and August.

“It tells us that our notion that it is the best and the brightest who effortlessly rise to the top is much too simplistic. Yes, the hockey players who make it to the professional level are more talented than you or me, but they also got a big head start, an opportunity that they neither deserved nor earned. And that opportunity played a critical role in their success.”

Gladwell points out that with cut-off dates for selection in sport, players born in the second half of the year have all been “discouraged, or overlooked, or pushed out of the sport”. By personalising success, some miss opportunities to reach the top rung, achievement is frustrated and people are prematurely written off as failures.

Two or three cut-off dates throughout the year could develop athletes on separate tracks and selectors should wait to pick all-star teams later.

“If Canada had a second hockey league for those children born in the last half of the year, it would have twice as many adult stars,” claims Gladwell. “Now multiply the sudden flowering of talent by every field and profession. The world could be so much richer than the world we have settled for.”

He has a point, but Gladwell overlooks the doubling of resources required to stream, coach and differentiate a second group of those being groomed for the elite. And is there really that much unfulfilled talent out there?

This is not a book primarily about sporting success but there are nevertheless fascinating chapters - on why some planes are more likely to crash than others and why the Chinese are so good at maths - that make it worth the detour.

Critics have accused Gladwell of alighting on four or five main points and stretching them to make a book, and each chapter could easily be a standalone essay on a similar theme.

However, Gladwell’s engaging style means Outliers is an easy read and the reader is not left out. The author also provides little diverting tests here and there, such as: “Why are manhole covers round?” You’ll have to read the book to get the answer.

Outliers - The Story of Success, Malcolm Gladwell. Penguin 309pp.

Editor's Picks

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Pressing principles

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

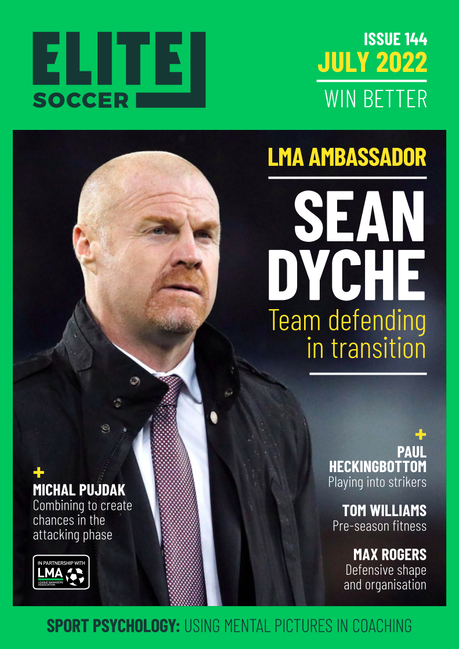

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.