ZOOM Q&A WITH KEITH ANDREWS - FEB 25 - DETAILS HERE

You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

How to Coach without bullying

One of the goals of coaching is to develop better decision makers - not just in executing the right tactics, but also in knowing when to use the correct technique.

In soccer, we might want our players to time a precision pass that creates a goalscoring opportunity – a technical decision. Or we might want them to press the ball from a certain position on the pitch – a tactical decision. The debate about what the best way is of enabling players to become skilled decision makers - and therefore better players - is at the core of this book, which comes down squarely on the side of getting the players to learn for themselves, rather than be told.

‘Athlete-centred Coaching - Developing Decision Makers’, is edited by Lynn Kidman and Bennett Lombardo. Kidman is a coach educator, currently working as a lecturer in sports coaching at the University of Worcester. Lombardo is professor of Health and Physical Education at Rhode Island College. Together they are probably the leading proponents of the benefits to come from coaching evolving towards an athlete-centred approach.

So what is athlete-centred coaching? Coaches that embrace this approach believe in sharing power with players, want the athletes to take ownership of their learning, and they refuse to dominate – a far cry from the domineering, often overpowering coaching you might see on any Sunday morning on any given training ground. Athlete-centred coaching is the precise opposite of coach-centred coaching, which is characterised by the coach setting the agenda, and doing all the teaching.

Coaching centred on the athlete also looks different. Coaches question more often and direct less, to tease understanding from the players. They will use games to generate understanding and learning rather than instructions. They will develop a team culture of respect and aim to help players to be the best they can be rather than concentrating on the team winning. They are more likely to empathise than bully. “They all want to develop athletes as people, not just as sports jocks,” say the authors.

Kidman and Lombardo are open about why they want more humanistic coaching. The experiences of children and adults playing sport make or break their decision to continue playing for life. They argue that when winning is the only focus, the development of the individual tends to diminish, and when athletes are pushed too young this leads to injury. And they are scathing about the “dehumanising” practices used by some coaches to enforce their control, seen most prominently in the professional environment where the pressure to win is greatest.

The philosophy promoted will worry traditionalists who believe that this is yet another step towards a generally soft approach in society that seeks to protect the individual from realities of life and blunts the competitive spirit. For those coaches who have success with a militaristic, authoritarian approach, it may simply be rejected out of hand.

One of the main contributors to the book, Mike Ruddock, the Wales Grand Slam winning coach and director of rugby at Worcester Warriors, illustrates how easy it is to be swayed between these opposing coaching credos, despite being a strong advocate of the athlete-centred approach.

Recalling his coaching career, Ruddock remembers reverting sharply to the authoritarian method while working in Ireland during a period when he was finding success elusive. An authoritarian approach by another coach seemed to work, so Ruddock tried it out and it also worked. But only for a short time. Then things started to go wrong again, with players leaving and results fading. He has since returned to his original method which, he says, gleans much greater long-term success.

At the heart of the debate is the reality that winning and long-term enjoyment of sport are two different things. Or rather there can be more than one definition of ‘winning’, ranging from winning a game, to winning by achieving personal goals. In addition, individuals learn differently, with some needing and expecting more robust leadership and others having the aptitude to develop themselves.

Whether the old school like it or not however, the authors’ views are being reflected (and in some cases have prompted) the athlete-centred coaching process to be a key component of many national coaching bodies’ methodology. Game officials have accepted the arguments that to promote the best long-term athlete development, starting too early and too competitively is out. As dropout rates are increasingly scrutinised as a leading measure for the health of a sport, they are acutely aware that for individuals to remain playing after childhood the activity must be more enjoyable.

Three practices at the heart of athlete-centred learning

-

A clear team culture - The culture covers the standards and values of how a team operates, covering ‘the way we do things’. “A team without a vision or team goals is like a team without a rudder,” say the authors. A coach must establish the goals for the season and a strategy to meet them. He or she must formulate the values of the team and develop strategies to meet them. Finally, the coach must create a single mission statement, and practise and reinforce the values.

-

Using games for understanding - This is an approach that uses purposeful games for athletes to learn skills, techniques and tactical understanding of a sport. The emphasis is on the player to solve problems posed by the game or one’s opponents through learning in context. This approach favours ‘just playing’ over drills.

-

Questioning - Rather than the coach being the font of all knowledge and the transmission of information being one way – from coach to player – a questioning approach helps athletes learn to ‘problem solve’ themselves. Coaches can feel uncomfortable using questioning compared to the direct approach as some believe it shows weakness, however it is a method of ensuring that players understand.

The authors acknowledge the dilemmas with an athlete-centred approach. Following such a method takes more time than is often available. For amateur, volunteer coaches already giving up large amounts of precious time, it is unrealistic to suggest they should further increase their commitment.

The book does come with some technical issues perhaps stemming from the authors’ determination that it is first and foremost an academic work. But even a dedicated researcher into this subject will tire at the overly lengthy verbatim quotations from interview subjects that cry out to be cut down to size. Even withstanding some needy repetition of the core philosophy, some judicious editing of interview subject quotations might have slimmed this volume down to a leaner and meaner 200 pages with little loss of impact, and made it more accessible.

Athlete-centred Coaching - Developing Decision Makers, Lynn Kidman and Bennett J. Lombardo. IPC Print Resources.

Editor's Picks

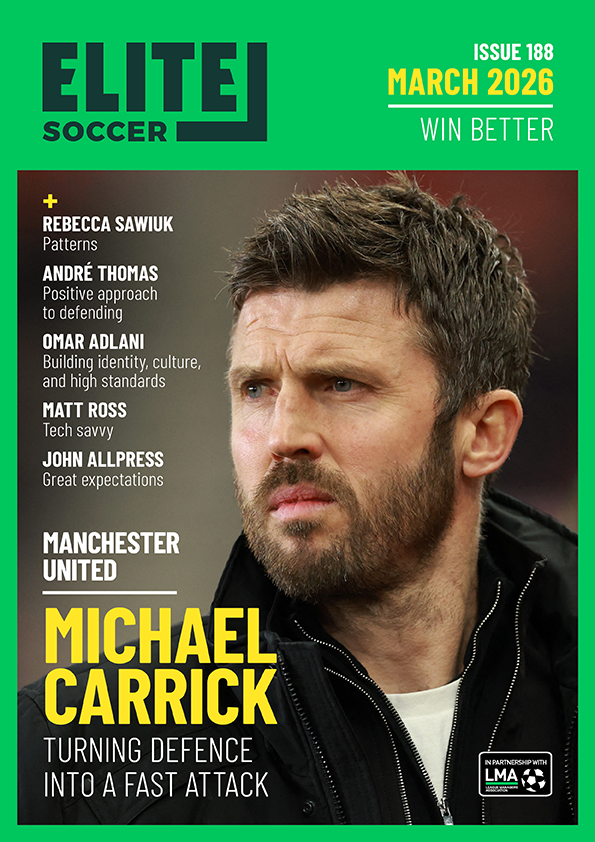

Turning defence into a fast attack

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

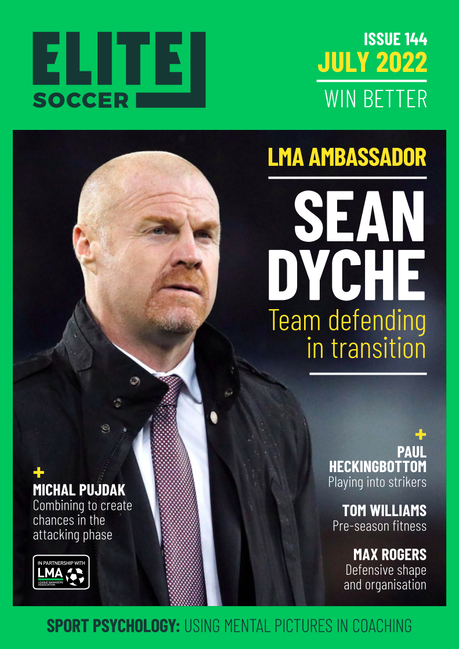

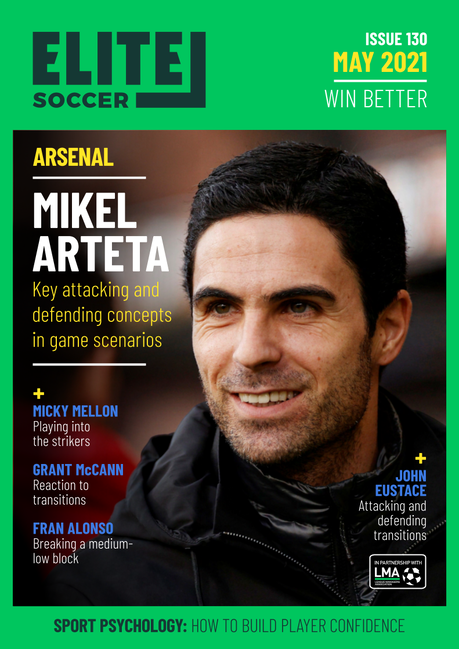

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.