OUR BEST EVER OFFER - SAVE £100/$100

JOIN THE WORLD'S LEADING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME

- 12 months membership of Elite Soccer

- Print copy of Elite Player & Coach Development

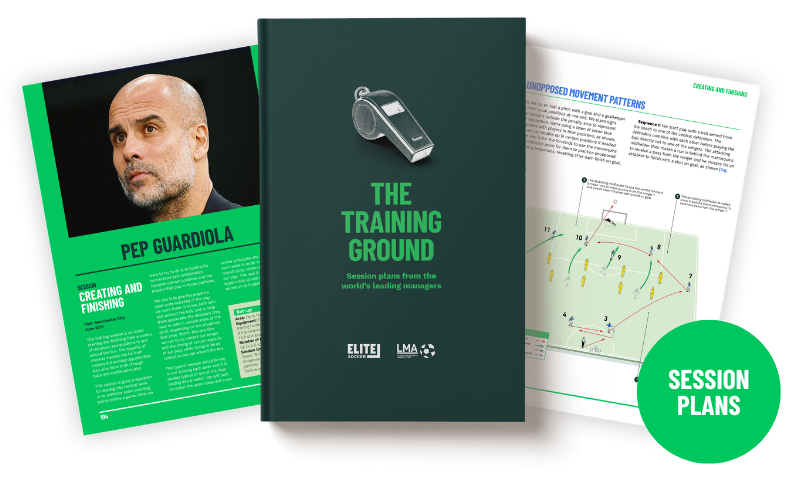

- Print copy of The Training Ground

You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

If at first...

The enemies of practice are pride and fear and self-satisfaction. To practise requires humility. It forces us to admit that we don’t know everything. It forces us to submit to feedback from people who can teach us.”

Thus begins Doug Lemov’s well-written but rarely epiphany-inducing guide to improving your skills as a teacher.

Lemov, author of the US best seller Teach Like a Champion, breaks refining your coaching skills down into seven chapters as his 42 rules unfold.

The chapters are of differing lengths with most pages given over to “the culture of practice” whereby you make training fun, competitive and blame free.

But you already knew that. And, to be honest, you will already have known quite a lot of this book as you will have heard its messages on courses, CPD courses and corporate company days.

That’s not to say Lemov deals only in platitudes and sound bites. Constantly driving home his message in parables about tying up shoelaces, sales managers, teachers, violin players and baking, as well as sport, he shows how your everyday honed skills are the ones you can take into coaching if you simply apply the same rules.

He starts by reminding you of how hard it was to learn to drive but now it’s automatic and you often do your best thinking while driving and can also handle most road problems that come your way as a matter of course. He also reminds you it is estimated you need 10,000 hours’ practice to become world class at something.

So this is not a difficult, stodgy read, just one that restates many points you have heard before.

This makes it a great reference book and one that, if read over the course of a week and revisited regularly, is insightful enough to knit coaching teams together and give head coaches a few fresh phrases and directions.

There are obvious rules: make sure you check for understanding, make sessions attainable, practise the basics so often they become automatic skills, increase intensity, put things into context, don’t always use just drills, correct rather than criticise, isolate skills, have a plan, don’t waste time, use demonstrations regularly but only ones that are correct, use video analysis, keep feedback short and snappy then work immediately on what you have spoken about, don’t ignore errors so they become the norm, encourage players to tell each other what their strengths and weaknesses are… you get the picture.

Each rule is summarised with bullet points so you could just read these, but then you would miss their context and worth.

Perhaps the one rule that coaches at all levels will recognise without realising they were at fault is 39: “Coach during the game (don’t teach)”.

We have all done it but, as Lemov says: “Coaching during a game can be helpful but teaching during a game is distracting and counterproductive. You can’t learn and perform at the same time.”

He adds: “The coaching that you do during a game should only reinforce, with reminders, what has been taught in practices.”

He advocates “short, positive phrases” during the game. This is simple, basic stuff but how many of us have seen our players struggle and tried to change things completely to a system barely touched on in training? Then we wonder why things got even worse…

Of all the rules, that one drove home the most, and there is no coach, regardless of the sport, who has not been guilty of this at some stage.

Another very interesting rule is number 2: “Practice the 20”. This is based upon the economic assertion that 80 per cent of results come from 20 per cent of the sources – the “law of the vital few”.

So the message is not to over-coach or try to teach too much. Lemov points to “the football team that works together so well that even when everyone in the stadium knows they’re on the charge, they’re still unstoppable”.

He adds: “The value of practising something increases once you’ve mastered it…. Your goal with these 20 per cent skills is excellence, not mere proficiency”.

Referring to Barcelona’s rondos drill (4/5 players in a square, one-touch passing while two players try to get the ball), Lemov quotes midfielder Xavi saying rondos is “the best exercise there is”.

“The value of the drill doesn’t decrease as they get better at it, it increases,” says Lemov, concluding that concentrating on the 20 means “you’ll no longer waste time preparing a smorgasbord of activities that you’ll use briefly and discard”.

Lemov’s final chapter, ‘The Monday Morning Test’ draws everything together and suggests various rule combinations for clubs, head coaches and just yourself as a person.

We could list all 42 rules here but without Lemov’s jaunty prose to move them along, that would just be a dull list. This book deserves better.

Two final thoughts: “Hustle and bustle can distract us from noticing when we’re not actually that productive,” so Lemov urges you not to confuse activity with achievement. However, “to be significantly better you need to be significantly more productive in every minute that you practise. Fortunately, ‘great’ is often not that far from ‘good’, and even small changes can increase by striking a degree at which people develop”.

So it’s not all bad news…

PRACTICE PERFECT: 42 RULES FOR GETTING BETTER AT GETTING BETTER, Doug Lemov. Published by Jossey-Bass.

Editor's Picks

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.