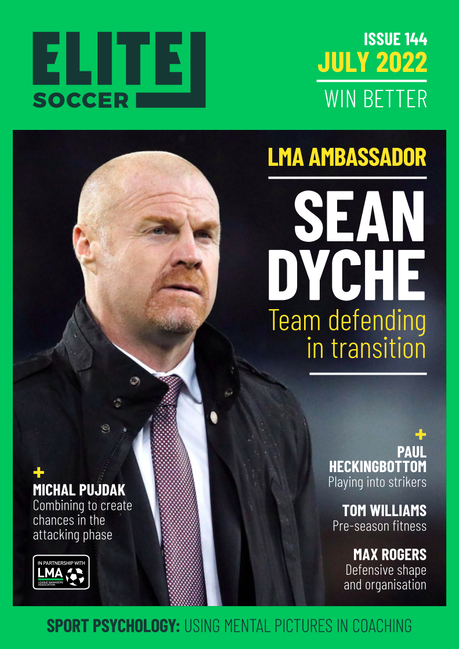

You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Nurture not nature

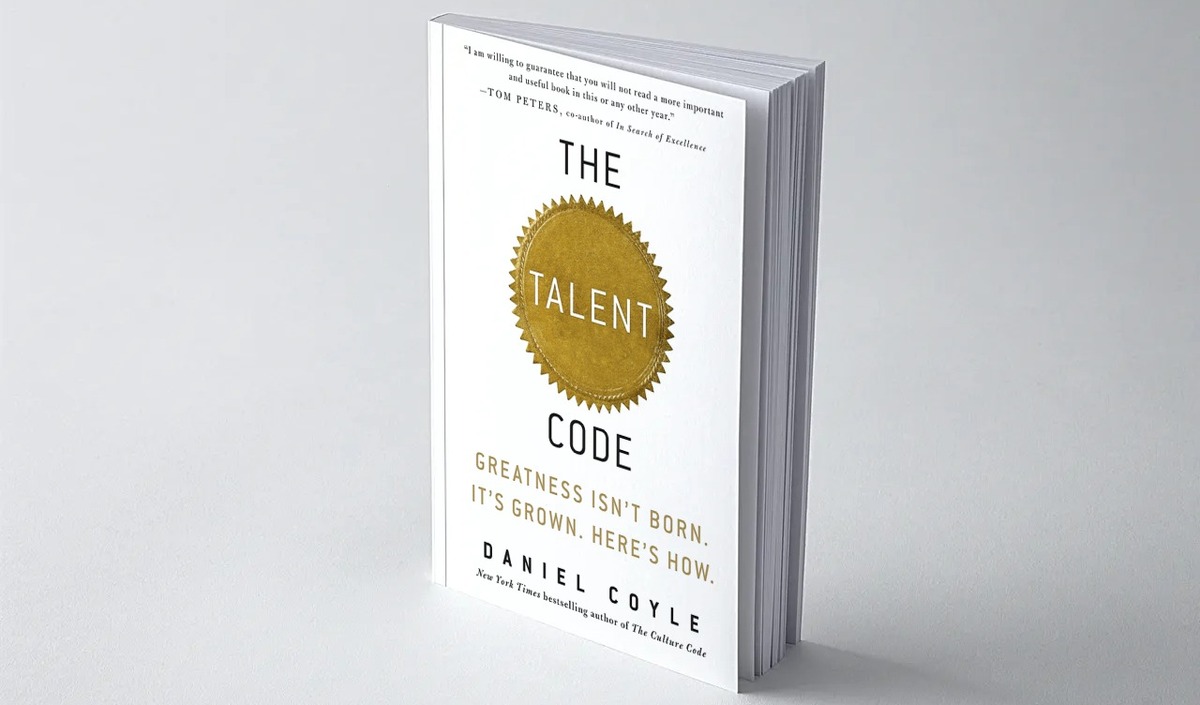

The Talent Code attempts to raise understanding of the nature and cause of top performance through an in-depth study of the neurological mechanism that explains why certain patterns of targeted practice build skill. What makes it a worthwhile read for coaches is that the author pays attention to how the new science underpinning excellence relates to the role of coaching.

Much of The Talent Code is concerned with explaining the relatively newly-discovered role of a human substance called myelin. Myelin grows around nerve cells, insulating them and making the cells more efficient at passing electrical signals to muscles. The more a nerve signal is fired, the more myelin wraps around the nerve and the faster the nerve signal travels. Only recently have we understood that myelin, in effect, creates “human broadband”, enabling signal speeds up to 100 times faster. Faster signal speeds equate to faster impulse speeds and ultimately the ability to deliver greater skill. Individuals who practise obsessively, who have a “rage to master”, are wrapping their neural circuits with ever more insulation that makes them increasingly efficient. Far from being genetically programmed, the evidence increasingly stacks up that world class performers in any discipline are created from perfect practice, deliberate practice, or whatever phrase is used to describe the process of dedicated, concentration on skill improvement in a particular, focussed way.

Experienced coaches might respond with a ‘so what?’ As long as the results are delivered, they will be less concerned with knowing why a particular coaching outcome is achieved, than by the fact that it is, or that progress is made toward a goal. Perhaps this explains why when outlining the fundamental role of myelin in conversation with Robert Lansdorp - the tennis coach of former world number one players Pete Sampras, Tracy Austin and Lindsay Davenport - Coyle admits he got something close to short shrift. “Sure, of course. It has to be something like that,” said Landsdorp.

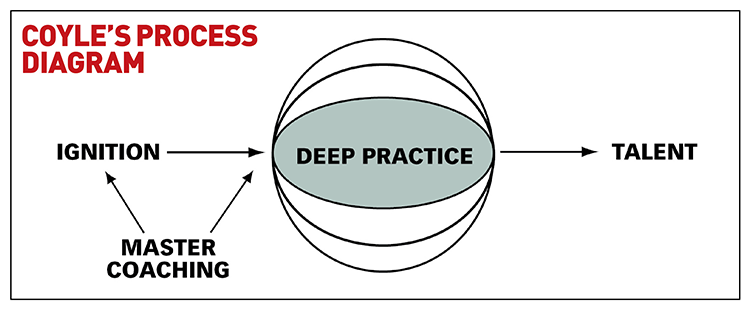

But Coyle’s analysis of the why does lead to some insightful observations about the nature of practice, and coaches everywhere faced with scepticism about their approach need supporting evidence. There are, Coyle says, three rules of “deep practice”.

The first is to “chunk it up” by which he means looking at the task as a whole –in soccer, perhaps this might mean watching a game – then breaking down and slowing down the component parts of a skill and ensuring that they are performed precisely. In soccer, an example would be a concentration on achieving top quality passing skills (passing with either foot).

The second rule is that when, and only when, a skill has been performed correctly, it should be repeated, thereby reinforcing the layers of myelin around the neural circuit. For ball sports this means drills.

Thirdly, Coyle says performers need to learn to feel it, by which he means they should personally understand and know the characteristics of most productive practice.

The upshot is that players, performers and artists could all benefit and potentially achieve world class performance from perfect practice. So why don’t more do so? The answer is a lack of what Coyle calls ignition, something which most would perhaps describe as motivation. “Deep practice isn’t a piece of cake: it requires energy, passion and commitment. In a word, it requires motivational fuel.”

Individuals don’t put in the hours needed (10,000 according to the research) to achieve mastery of a discipline without a spark, or a series of nudges, and then something to sustain the motivation. The spark can be the breakthrough success of an individual in a country that leads to the creation of a hotbed and then a bloom of talent. A good example is South Korean female golfer Si Re Pak, who became a national icon after winning the LPGA Championship in 1998. In 10 years South Korea has come to dominate the ladies game with 45 players winning one third of the LPGA Tour events. Si Re Pak is the Tiger Woods of her country.

The coaches of individuals who become world class play the role of “talent whisperers” according to Coyle. They have generally been coaching for 30 or 40 years. The author met many over two years whilst writing the book. They were “quiet, even reserved… possessed the same sort of gaze: steady, deep, unblinking. They listened far more than they talked.”

Coyle links top coaches with the essential ingredients of deep practice by showing how they act as strict controllers of individual training actions.

As evidence he presents an analysis of the techniques used by US basketball coach John Wooden. Whilst coaching, his comments were “short, punctuated, and numerous”. There were no lectures or monologues. Wooden rarely spoke for more than 20 seconds. Researchers who followed Wooden observed and coded 2,326 separate, individual acts of teaching. Only 6.8 per cent were compliments, only 6.6 per cent were expressions of displeasure. Around 75 per cent was neutral: pure information. Wooden was seeing and fixing errors, constantly correcting actions to ensure deep practice was taking place, and then ensuring they were repeated until they became automatic.

Those from the school generation that can remember “rote learning” – one manifestation of which was the now unfashionable attachment to repeating times tables – will be amused at Coyle’s conclusion that ultimately learning is about repetition.

But from the coach’s view, an all-consuming attention to error correction is not enough. The Talent Code is more than the science of coaching. Coyle’s analysis does not overlook the art nor downgrade the thousands of teachers and coaches who will never be lauded as the best or the most talented. Even “average” teachers, he says, can be responsible for lighting the fire of motivation that leads to greater things by creating and sustaining interest through personal attention and love.

The Talent Code captures both the simplicity and yet the complexity of what is needed for good coaching leading to world class talent development. He rightly lets the last word go to Tom Martinez, a retired US college American Football coach, still approached today for his wisdom by those in the game, and whose insight sentiments illustrate something ethereal about coaching that can never be codified.

The Talent Code - Daniel Coyle. Arrow Books 246pp.

Editor's Picks

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Pressing principles

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.