OUR BEST EVER OFFER - SAVE £100/$100

JOIN THE WORLD'S LEADING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME

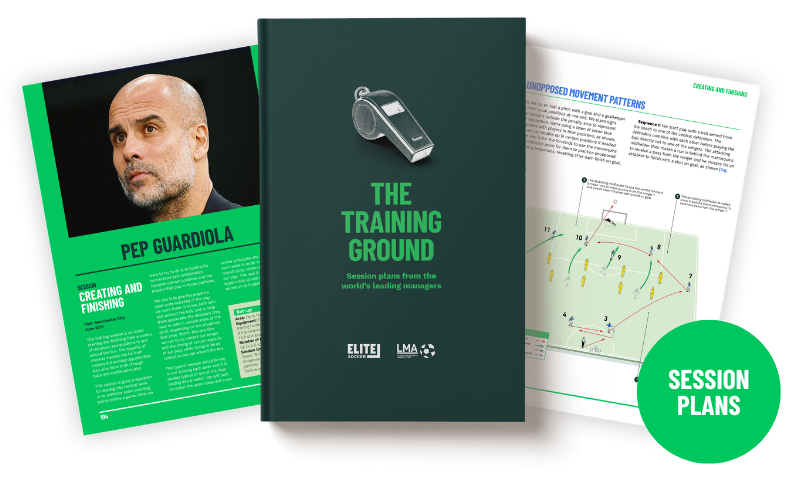

- 12 months membership of Elite Soccer

- Print copy of Elite Player & Coach Development

- Print copy of The Training Ground

You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Practice, practice, practice...

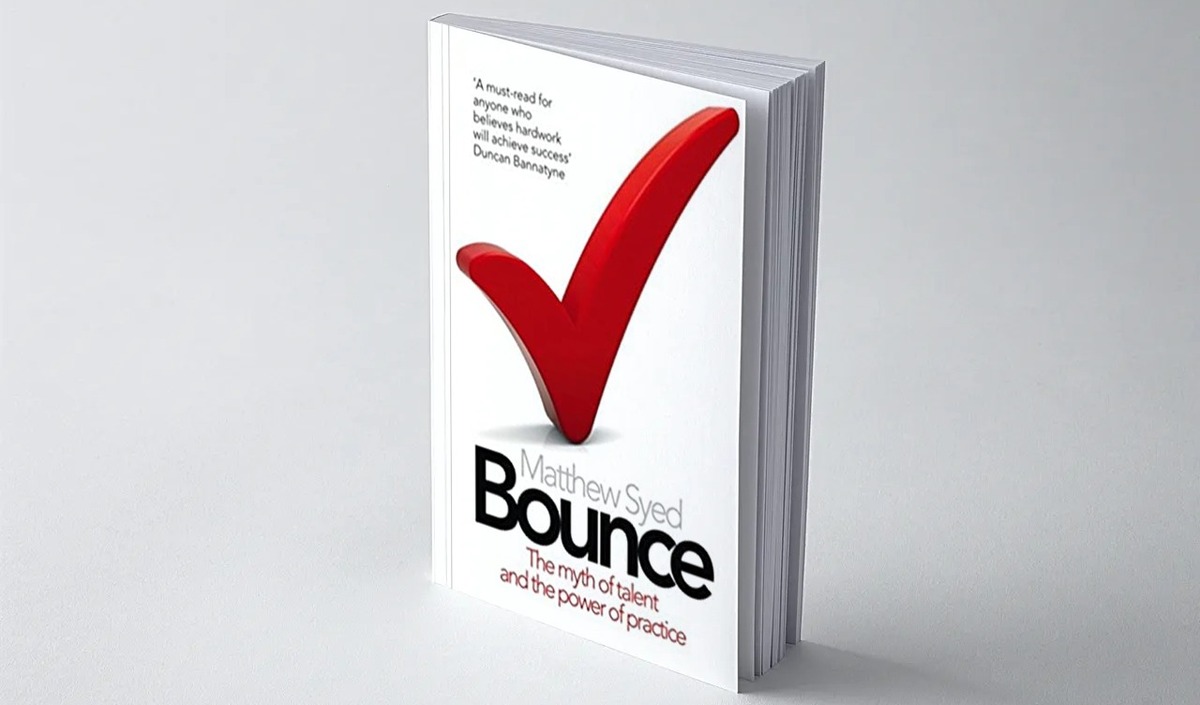

Matthew Syed came from an ordinary family and claims to have possessed little in the way of sporting talent. Yet he became the British table tennis champion, holding the title for ten years, before becoming a national newspaper sports writer. So who better to assemble the compelling evidence that sporting geniuses are not born but created. Bounce shows with dazzling clarity how genetics plays a very much smaller part in the development of sporting superstars than has been previously assumed, and convincingly explains how circumstances, chance, and above all practice are the overwhelmingly dominant factors in the achievement of excellence.

Syed’s fascinating analysis of how he got to the top shows how these factors can come together in a random way. For no particular reason that he can ascertain, his parents bought a table tennis table when he was eight. It was set up in the garage, and was permanently accessible. Matthew had an elder brother and they played endlessly. A teacher at his primary school happened to be the country’s best table tennis coach. Matthew and his brother were introduced to a local table tennis club. They trained before and after school, at weekends and in the school holidays. This head start for Matthew and his brother (who also achieved table tennis greatness) combined with a top coach and a strong local club, made the difference. But he was not the only one. It turns out that within a few streets of his Reading primary school no less than 11 junior and senior table tennis champions emerged from the same generation. Syed himself poses the question: what would have been the outcome if he had lived in a different Reading street, and attended a different primary school?

The evidence from Syed’s own story and those of many others, that it is not what champions are like that matters, but where they are from, is stunning. Although Syed has met many top sportsmen and women, he freely attributes most of the collateral for his arguments to others. He acknowledges his debt to the researcher Anders Ericsson of Florida State University, the social commentator Malcolm Gladwell (Outliers), and authors Geoff Colvin (Talent is Overrated) and Daniel Coyle (The Talent Code).

The most extensive investigation into the source of outstanding talent was undertaken by Ericsson among violinists from the Music Academy of West Berlin in Germany. He divided them into three groups. Outstanding students expected to become international soloists, extremely good players destined for positions in leading orchestras, and a less able group with a future as music teachers. The question posed was what separated the three groups? The biographical histories of the three groups were similar and showed no marked differences. They started formal lessons and practice aged eight, and all decided to become musicians aged around 15. The only real difference between the groups was simply the number of hours devoted to serious practice. By the age of 20, the best violinists had practised an average of 10,000 hours – more than 2,000 hours more than the good violinists and more than 6,000 hours more than those hoping to become music teachers.

This finding has become known as “the 10,000 hour rule” – the minimum time believed necessary for the acquisition of expertise in any complex task. Syed steps back to point out that implications are far wider than simple for sporting achievement and apply to work, business, politics, and life in general.

“If we believe that attaining excellence hinges on talent, we are likely to give up if we show insufficient early promise. If on the other hand, we believe that talent is not implicated in our future achievements, we are likely to persevere.”

Bounce is full of examples that prove how the roots of so-called talent seen in top sports people, such as lightning reaction speeds, astonishing anticipation, and instinctive movements, are actually the product of enhanced brain processes developed through practice. World-class tennis players can tell where a serve will land based on the tiny changes to the server’s hips and body position. Chess players “chunk” the information on the board in front of them rather than perceive the position of each individual piece. These performers were not born with this ability – it has been gained through experience. Syed highlights Desmond Douglas, also a British table tennis champion, renowned for his fast reaction speeds. To the sport’s surprise when Douglas actually had his overall reaction speeds tested, he turned out to be no better than sluggish. The findings were such a shock that at first no one believed them. On further investigation by Syed, who looked deeply into the player’s early playing history, the explanation became clear. Douglas had spent the first five years of his table tennis life in a cramped Birmingham classroom with so little space between the end of the table and the walls that the players developed a form of “speed table tennis”. “Douglas spent more hours than any other player encoding the characteristics of a highly specific type of table tennis: the kind played at maximum pace, close to the table. That is how a man with sluggish reactions became the fastest player on the planet.”

Practice alone however is not enough. It must be deliberate, purposeful practice. This means not just repeating easy actions and skills, but challenging a player with new and more difficult options until they are “second nature”.

The ascendancy of Brazil as the world’s leading soccer nation is, in the popular perception, due to the free flowing style of play and skills developed in beach football. However, increasing evidence shows that in fact it is the far more widely played game of futsal – contained within a smaller pitch with fewer players and a heavier ball, leading to more touches per player and greater control of the ball – which is in fact the root cause.

For those with an interest in the physiological side of performance Bounce provides plenty of material from psychologists and sports scientists as to how the brain moulds itself and the motor skills that it controls as a result of thousands hours of practice. Movements and reactions become hard-coded in the neural pathways of the brain, creating the impression that highly skilled actions are innate.

Syed also writes about the role of motivation and faith and belief, other key ingredients in the of a world-class performer in sporting discipline. The sections of the book highlighting the placebo effect and a discussion on the role of drugs and drug abuse, are perhaps parallel debates that whilst are arguably relevant to analysis of superior performance, are not central to the main theme of the book. To that extent they seem tacked on.

Bounce has nothing to say about team performance, though the principles laid out in this book that underpin individual achievement surely must be applicable to groups of performers. For coaches of team games the inescapable conclusion is that constant repetitive purposeful practice, whether in drill-based activities or game-based play, is the key to achievement.

Bounce - How Champions Are Made, Matthew Syed. Fourth Estate 296pp.

Editor's Picks

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.