OUR BEST EVER OFFER - SAVE £100/$100

JOIN THE WORLD'S LEADING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME

- 12 months membership of Elite Soccer

- Print copy of Elite Player & Coach Development

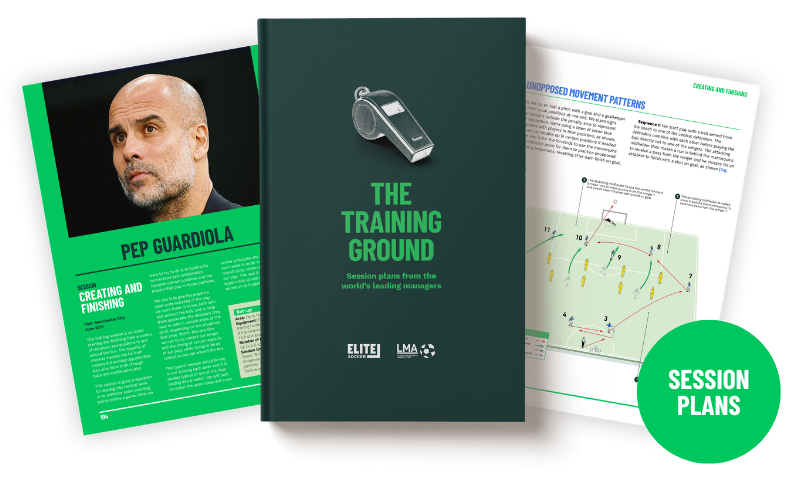

- Print copy of The Training Ground

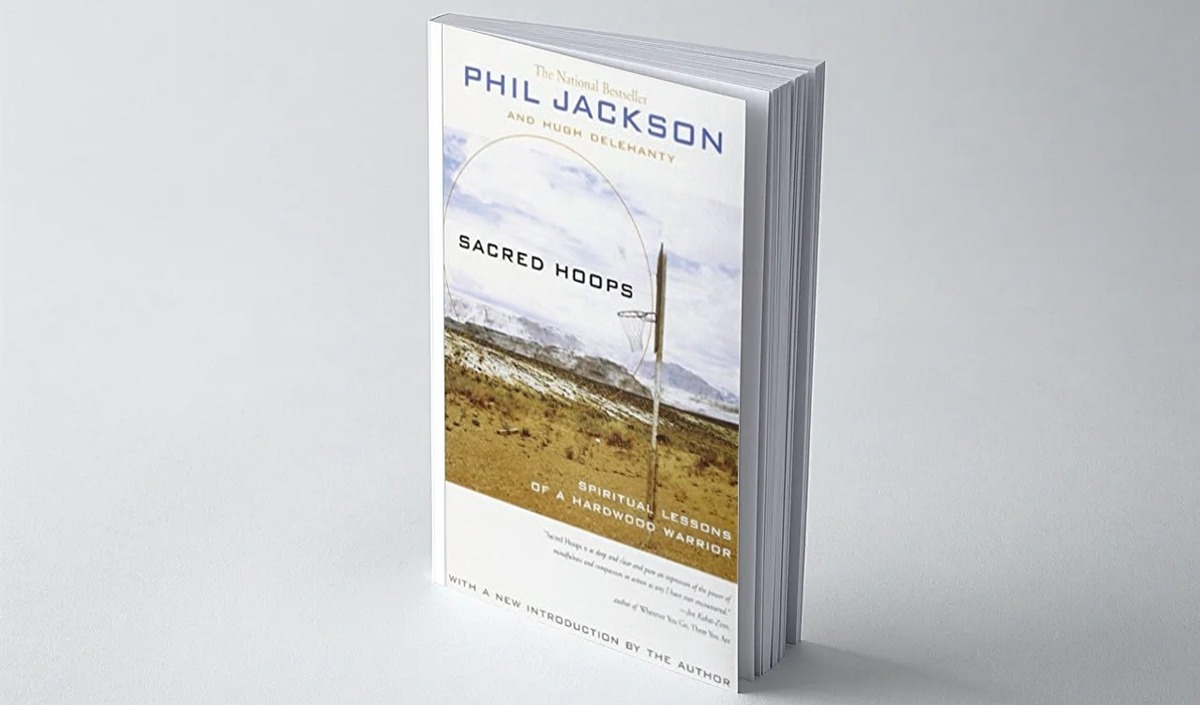

Sacred Hoops

Phil Jackson is up there with the best basketball coaches in history, enrolled in the sport’s Hall of Fame with a record 11 National Basketball Association (NBA) titles. With the Chicago Bulls (aided by one Michael Jordan – undisputably the best basketball player in history) Jackson won the NBA title three years running – twice. Proving that it was not all about Michael Jordan, Jackson then went on to win five NBA titles with the Los Angeles Lakers between 2000 and 2010.

Jackson supplemented his knowledge as a title-winning New York Knicks player with teachings from Zen Buddhism and the Lakota Sioux Indians, earning himself the nickname ‘Zen Master’. He decorated his team room with native American totems and symbols and started and ended each practice with the players in a circle to symbolise forming a sacred hoop. He even tried to get the bull on the Chicago logo replaced with a white buffalo (a sacred Indian symbol) but that was considered going too far.

Jackson believes that what drives most basketball players (and presumably most sportsmen and woman) is not money or adulation but their love of the game. “They live for those moments when they can lose themselves completely in the action and experience the pure joy of competition.” One of the main jobs of a coach, he believes, is to reawaken that spirit so that the players can blend together effortlessly.

The core of Jackson’s vision was getting the players to think for themselves. When he took over at the Bulls, the younger players were used to being berated by their former coach when they made mistakes, and would look at Jackson after an error, expecting to be admonished and told what they had done wrong. “Why are you looking at me,” he’d ask. “You already know you made a mistake.”

Being in the moment and not thinking characterises Buddhist thinking and Jackson made big efforts to get his players into a “cocoon of concentration” without shutting out the world. One method was to practise meditation so that the players could experience stillness of mind or mindfulness, in a low pressure setting off the court.

Getting players to meditate caused amusement for some. One said it gave him extra time to take a nap. However, Jackson insists that even those players who didn’t really engage got the basic point that awareness is everything. Occasionally, he would conduct an entire on-court practice in silence, forcing players to concentrate and use non-verbal communication. Jackson said the results never failed to astonish him.

Being mindful means resisting distractions. Though it didn’t always work, players were advised that when they were fouled by opponents they should take a deep breath, stay composed and focus on the goal: victory. Getting buy-in for this non-belligerent approach required continuous reinforcement, admits Jackson, particularly in such a physical sport.

Against their arch-enemies, the Detroit Pistons, in 1991 “everyone on the team was slammed around” but they laughed it off and the Pistons didn’t know how to respond. “We completely disarmed them by not striking back.” That is not to say that the Bulls didn’t give as good as they got on occasions, when Jackson admits he lost control.

As a coach, Jackson wanted to take a middle road between a relaxed approach – letting players do what they want – and what he accuses many coaches of being: “control-oholics”. He identifies with a style described as “compassionate leadership” by management consultant James O’Toole. This leads with the pull of inspiring values, rather than the instinctive push of ideas and instructions - particularly difficult to avoid when things are going badly. The ultimate goal of a value-led leadership philosophy is that the leader becomes ‘invisible’.

“I wanted to create a team in which selflessness – not the ‘me first’ mentality that had come to dominate professional basketball – was the primary driving force,” said Jackson.

One of his trademarks was giving everybody equal or close to equal playing time. While most NBA teams use seven or eight players regularly, Jackson tried to use all 12 in the squad in rotation. In a 1992 game against the Portland Crusaders, the Bulls were down by 17 points in the third quarter and sinking fast so Jackson put on his second unit. His staff and the press thought him mad but within minutes the subs wiped out the deficit and put them back in the game. One wonders how many times this tactic would work and whether Michael Jordan and other stars were really regularly asked to be benchwarmers.

To realise his vision, Jackson acknowledges that he had to win over Michael Jordan, telling him: “You’ve got to share the spotlight with your team mates because if they don’t, they won’t grow.” Basically, he was asking the world’s best basketball player to give up the ball and take fewer shots.

Jackson addresses the challenge of coaching genius in a dedicated chapter. Jordan said he didn’t need “that Zen stuff” and Jackson concedes that the star already had a positive outlook on life and quality of mind, which allowed him to stay relaxed and focused.

Jordan rarely got depressed, bounced back from failure, and had a mesmerising effect on other players which could lift the mood of a team. Jackson believes Jordan was transformed from a gifted solo artist into a selfless team player during the time under his wing. This occurred after Jackson apparently explained to Jordan that the sign of a great player is not how much they score but how much they lift their team mates’ performance.

There’s only so much a coach can do to influence the outcome of a game. Jackson believed that if you push too hard to control what happens, resistance builds and “reality spits in your face.”

Jackson said he was far more effective as a coach “when he balanced the masculine and feminine sides of his nature. I find that when I can be truly present with impartial, open awareness, I get a much better feel for the players’ concerns than when I try to impose my own agenda.”

But he rigidly adhered to his philosophy despite being up against the money culture of modern basketball, where the stars with dramatic eye-catching moves are paid astronomical sums and the team players get the minimum wage. “With so many people telling them how great they are, it’s difficult and, in some cases, impossible, for coaches to get players to check their inflated egos at the gym door.”

His dedication to the Triangle Offense empowered everyone in his teams by making them more involved in the offense, and demanded that they put their individual needs second to those of the group. Jackson says: “This is the struggle every leader faces: how to get members of the team who are driven by the quest for individual glory to give themselves over wholeheartedly to the group effort. In other words, how to teach them selflessness.”

Not everyone agreed with his approach. When Jackson was employed one summer early in his career at the Quebradillas club in Puerto Rico, he was fired after three weeks because the team’s superstar didn’t like the selfless system of basketball he had implemented.

Sacred Hoops - Spiritual Lessons of a Hardwood Warrior, Phil Jackson. Hyperion Books 224pp.

Editor's Picks

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Related

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.