NEXT ELITE SOCCER COACHING AWARD COHORT STARTS FEBRUARY 16 - ENROL NOW

You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The power of the mind

The way you view your own intelligence can determine how successful you are in life. That’s the premise from Carol Dweck, an American educational psychologist, who believes that the achievement of one’s full potential in business, parenting or coaching comes down to one thing: mindset.

Dweck claims to have established in her research that people tend to have either a “fixed mindset” or a “growth mindset”. Those with a fixed mindset largely believe that their intelligence, or talent, cannot really be improved, and that as a consequence tend to focus on looking smart, or at least not looking stupid. They avoid difficult challenges that “show them up” and hate making mistakes. Fear of failure means their learning and development of knowledge, skills and abilities is hindered.

Those with a growth mindset, on the other hand, view intelligence as a potential that can be developed. They put effort into learning and performing and into developing strategies that enhance learning and long-term accomplishments. An implication is that it pays off to help children and students invest in a view of intelligence as something that can be developed. Dweck does not deny that people differ in their natural abilities but she stresses that it is continued effort that makes abilities blossom. Children who have learned to develop a growth mindset know that effort is the main key to creating knowledge and skills.

How do you know if players have a fixed or growth mindset? Simply by challenging them, according to Dweck, with statements like: “You have a certain amount of intelligence and you can’t really do much to change it.” People who agree with this kind of statement have a fixed mindset. Those who have a growth mindset agree that: “You can always substantially change how intelligent you are.”

The illuminating case studies of coaches and business people throughout this intriguing book overcome a slightly leaden writing style, and references to sports players and coaches will appeal to readers looking to apply the lessons of mindset to the world of soccer.

Basketball player Michael Jordan wasn’t a natural, but he had a growth mindset. In his early years, though talented, he was not picked out as a star. He was dropped from his school team and wasn’t recruited by the college team he wanted to play for. But Jordan was a hard working athlete. His response to being dropped was to get up at 6am every day to practise. He worked on his weaknesses. He practised for hours after the last game of the year – to get ahead for the following season. One of his coaches commented that Jordan was “a genius who constantly wanted to upgrade his genius”.

Perhaps the best coaching example of fixed mindset is Bobby Knight, the controversial college basketball coach. Dweck says he could be unbelievably kind and gracious, yet was also monstrously cruel. He was incapable of accepting failure, taking every defeat personally. A loss made him a failure, obliterating his identity, and as a result he demeaned his players. Players deemed guilty of losing the game were banned from going home on the coach with the rest of the team, as they were no longer worthy of respectful treatment. He threw chairs across the court, grabbed players by the neck and exploded at the slightest mistake. This was justified as toughening up his team to play under pressure, but in reality he was out of control.

Was Knight a successful coach? Well, he won some championships, but Dweck quite rightly questions at what price this was achieved. Knight’s players spoke of a poisonous atmosphere and it was too much for some to bear.

Growth mindset coach John Wooden led the UCLA basketball team to championship victory in 10 out of 12 seasons, and once had a winning streak of 88 games. He started in 1963 with a weak team, poor facilities and a losing atmosphere, but with an approach that winning or losing was not the most important consideration. Players got equal time and attention. He didn’t ask for mistake-free games or demand that his players never lose. What he wanted was full preparation and maximum effort. “Did I make my best effort?” If so, he says, “You may be outscored but you will never lose.” But he would not tolerate coasting. If players were not putting in the effort during practice he was known to turn the lights out and inform his team that they had lost the opportunity to improve that day.

“There are coaches out there,” Wooden says, “who have won championships with the dictator approach, among them Vince Lombardi and Bobby Knight. I had a different philosophy… For me, concern, compassion, and consideration were always priorities of the highest order.”

Dweck provides some telling insights into how those with differing mindsets react to success and failure. Her theory is that those with a growth mindset found success by doing their best, by learning and improving. Setbacks, rather than being seen as demoralising or depressing, are seen as motivating, informative and a wake-up call. People with growth mindsets in sports take charge of the processes that bring success – and that maintain it.

The book is largely anecdotal and draws on biographical sources, and one criticism is that there is little hard data to back up what ultimately is still a theory. Having said that it is a convincing one – we all know people who operate in a fixed mindset – and Dweck has a talent for applying her psychological analysis to behaviours, drawing what seem like logical conclusions.

How can soccer coaches put Dweck’s theories into practice? David Clarke, the editor of Soccer Coach Weekly, organised drills for an Under-10s group designed to deliberately cause them to fail. It was a simple running and passing drill, but as he challenged them to perform better they at first made mistakes but then learned how to correct them, and improved. His conclusion: “Players need to feel comfortable in an environment where mistakes are accepted. At my last club I had a sign in the players’ changing room which simply said: ‘If you don’t make mistakes you aren’t learning.’”

Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Carol Dweck Ballantine Books 278pp / Amazon.

Editor's Picks

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

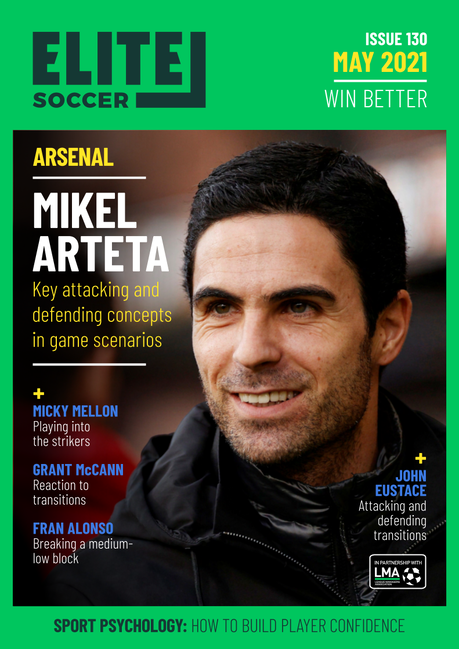

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.