You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The science and reality of skill acquisition

This book lives up to its subtitle by providing, in the words of top coaches, an insight into the reality of delivering skill development. Thankfully for ordinary readers, the way the coaches put it is easier to understand than the way the sports scientists sometimes do, otherwise Developing Sport Expertise would be a very dry read indeed.

As it happens however, whilst each of the 13 chapters is written by guest academics or one of the editors, the Coach’s Corner at the end of each one is provided by practising senior coaches from sports including rugby, swimming, basketball, football, cricket, rowing and hockey. This makes for some welcome light relief, plus some good explanations of the theory in practice.

Each chapter is also a specific discussion of one aspect of the latest (as of the 2008 publication date) thinking on an aspect of skill development as it applies to elite athletes, and the people who coach them. Overall, it is authoritative, well written and addresses some of the most intriguing questions in sport, such as what causes choking?

Perhaps the most relevant chapter for coach development is entitled Expert Coaches in Action. If you are interested in what makes a good coach and how you might become a better one, there are many suggestions here, some of them going against conventional thinking. What makes a good coach is unclear, as the measurement of success can really only be undertaken by measuring the success of a coach’s players. For team sports, winning is an obvious yardstick, yet that overlooks the impact of star players.

Researchers have therefore focused on other lines of questioning. These are:

What do expert coaches see that other coaches might miss?

Do expert coaches organise training sessions that are more efficient and effective than those of others?

The difference between expert and non-expert coaches has been highlighted by research, shedding light on these questions. In one experiment coaches were asked to observe video recordings of four swimmers of different skill levels, were asked to analyse the strokes and provide instruction. Novice coaches were vague and superficial in their analysis, while expert coaches were able to provide deep insight into the technical issues, could “see” more and offer better feedback. Intervention by expert coaches can therefore result in feedback and error correction that has an immediate and larger impact on skill development. Experience counts.

Regarding the second question, the answer from research is an unequivocal yes. It is the job of coaches to design deliberate practices that are the most effective at developing skills. Analysis of the coaching actions of the highly successful UCLA basketball coach John Wooden (featured in the last issue) showed that 75 per cent of his behaviours consisted of some form of instruction. The other key factor appears to be that Wooden, and others of his ilk, do not waste a second of time at practices. The authors point out that for team sports, practices that are even under constant supervision often suffer from under-utilisation of time. In one study of practices of high-level junior ice-hockey players it was found that they were inactive 48 per cent of the time. Contrast this with a similar study of practices undertaken by a volleyball coach which showed that her athletes were active 98 per cent of the time. Even the seven per cent if inactivity was rest breaks during which the coach continued to instruct.

The authors suggest that developing drills that simulate game scenarios is something that is common to all great coaches. Drills should match the physical demands that players face in matches, and the most inventive coaches will come up everything from games designed to score points in the dying seconds, to bringing fans to heckle. Wooden is said to have spent as much time preparing his practices as delivering them.

So much for the theory section. Patrick Hunt, a senior Australian basketball coach, ends the chapter with a plea for more research and information on what needs to be considered to develop coaching expertise, and area where research has only scratched the surface. He thinks coach education courses are vital but only a small part of the collection of tools and experiences that should be used to develop an expert coach. Among the others are playing experience, informal coach development experiences, trial-and-error practices, competitions and self-evaluation. “It might sound like a cliché, but the best coaches learn from every experience they have,” says Hunt.

Coaches will find the debate on the play versus practice moves on through a clear analysis. Not enough play and too much deliberate practice too early can lead to burn-out, injury and disillusion among players. Getting the balance right at the three key stages of athlete development (6-12, 13-15, and 16+) is crucial. Deliberate practice can only improve current performance and playing and having fun through sport is essential for children. Too much early specialisation in a sport should be avoided.

A down-to-earth view on this is provided by former Wallabies coach Eddie Jones at the end of this chapter with his observation that in his experience elite players that have played more different sports in their earlier years are tactically more astute. Those who specialised too early often show a lack of creativity. “Rarely do players initiate their own warm up with a ball. They have to be told by coaching staff to get underway. In past generations players would arrive early simply to throw the ball around before the formal training session began. A lack of creativity means we have fewer players with the decision-making skills required to win games of rugby,” says Jones.

Does practice make perfect? The link between performance and time spent practicing is almost a given a chapter on this subject emphasises that the quality and nature of practice is also important. How odd to think, as they authors point out, that Roger Bannister while preparing to break the four minute mile limited himself to half an hour or training per day, fearing that the human body could not take any more without damage. Modern thinking is that deliberate practice, in the right measure, is a requirement, and the authors have done well to find Shannon Rollason, head coach at the Australian Institute of Sport Swimming Program to explain what this concept means to him. “I always ask of my swimmers that if they are going to get into the pool to train then they must give 100 per cent and focus on what is required. Sometimes we can make this training fun, but often it is simply hard work.” Bringing a softer side to the coaching process, Rollason also points out that sometimes being a good coach simply means reading the signs in athletes in terms of their readiness to train. He uses body language, facial expressions and “what they do and don’t say” to assist him to formulate a training plan for the week or a given session.

Theory mixed with simple, practical advice. This is an in-depth analysis of sport expertise development with an element of accessibility that is missing in similar volumes.

Developing Sport Expertise - Researchers and coaches put theory into practice, Damian Farrow, Joe Baker, Clare MacMahon (editors). Routledge 215pp.

Editor's Picks

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Pressing principles

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

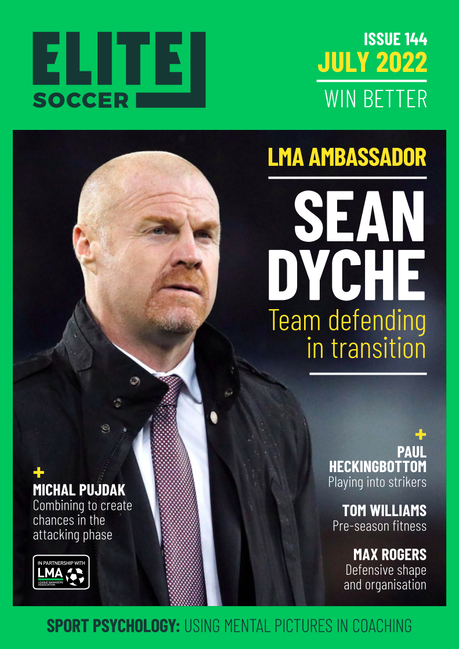

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.