NEXT ELITE SOCCER COACHING AWARD COHORT STARTS FEBRUARY 16 - ENROL NOW

You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

From all angles

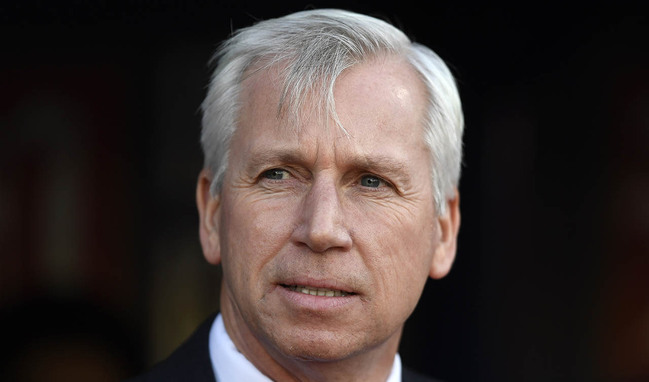

Alan Irvine reflects on his career journey in coaching and the importance of mentoring support to help newly appointed managers

Since his days as a professional footballer, LMA Technical Consultant and mentor Alan Irvine has worked in first team football in various capacities. However, it was only after completing his Pro-licence and LMA Diploma and working for 15 years as a youth coach, first team coach, academy director and assistant manager that Alan Irvine finally became a manager. Even then, by his own admission, he wasn’t fully prepared for everything the job would throw at him.

“I’m not sure I could have done anything more, and certainly I think you’re better prepared if you’ve experienced first team football, either as an assistant or a coach,” he says, “but I don’t think anything can fully equip you for your first day as a manager. It’s only when you’re sitting in that seat that you discover what the job is really like and for most people the reality is quite different to their expectations.”

Irvine is sure he would have benefited from having support from a mentor during those early days in the job and indeed throughout his tenures at Preston North End, Sheffield Wednesday, West Bromwich Albion and while caretaker manager of Norwich City. “I’ve had managers who I could bounce things off, but ideally you want someone who has been trained in the role of mentor,” he says. “There’s a skill to not giving answers to problems, but asking the right questions to help the manager come to their own decisions and solutions.”

What’s more, management can be a lonely job and sometimes you need someone outside of the club to speak to. Often as a manager there’s a long queue outside your door, and you’re presented with a wide range of problems, which you are expected to solve, says Irvine. “Everyone will turn to you for answers, but whose door do you then knock on when you need advice or support? Many managers are loath to bother their staff or to admit any doubts or concerns to those above them for fear of undermining their positions.”

While mentoring is common at the highest levels of business, it’s still relatively new in football, something Irvine hopes will change with the new LMA Mentoring Programme. “There’s still a degree of scepticism about mentoring among managers, so it’s important that we emphasise there is nothing to fear from it and so many advantages. Nothing is forced upon the manager, so they decide what kind of support they want or need, how informal they want the conversations and relationship to be, when and where meetings take place.”

Although Irvine didn’t have a formal mentor of this kind, he was fortunate to play under a number of great managers, among them Sir Kenny Dalglish MBE and Steve Coppell, and was watching and learning from an early age. He formed his own opinions of what to emulate and avoid, and as he matured became adept at modifying these approaches and ideas to develop his own style of coaching and leadership.

CHANGING ROLES

In his long career journey, Irvine has been a youth team coach, first-team coach, academy manager, assistant manager, caretaker manager and manager. Most recently he was assistant manager at West Ham United.

“I think I was a better assistant manager for having been a manager previously,” he notes, “because it meant I had greater empathy for the manager, an understanding of his thinking behind decisions and more awareness of the pressures that he would be under.

“I understood, for example, why he might have chosen not give an opportunity to a player or why he might not be able to come to watch every match. I’d know that if, on occasion, he walked straight past me in the canteen it was just because he was dealing with so much that his mind was somewhere else.”

Also key to making any relationship between the manager and assistant manager work, he adds, is clarifying the nature of the job from the outset. “That very first conversation you have with the manager before you’ve even been offered the position is vital,” says Irvine. “You have to establish what the expectations, limitations and responsibilities are. For example, I would never accept a job as assistant unless the manager was happy for me to speak my mind. I’d make that clear from the very start, because if they weren’t comfortable with it there’d be no point in entering into the relationship.

“You have to ask every question and lay everything out right at the start if you want the relationship to be as strong as possible.”

A PASSION FOR COACHING

Irvine also understands what the manager needs from his staff in terms of coaching and developing the players, and has an acute awareness of the kinds of talents and characters that can succeed at first team level. “The manager has a role to play in the development of the players, but he’s stretched, so the assistant and first team coach need to ensure the players are ready should the manager give them the opportunity to play and that they can handle all kinds of situations in the game.”

That includes being able to make decisions on the pitch, something he says that players are often unfairly criticised for. “If you want to improve players’ decision making you have to allow them to make decisions. I like to present players with as many different potential solutions to a problem as I can and then let them solve it themselves. You have to give them the freedom to decide what to do and to react accordingly.”

Regardless of the role he is fulfilling, Irvine says he’s much the same when it comes to dealing with the players. “When you’re the manager, you’re one step further away from them, so there’s a distance, but there’s also a closeness because you’re the person they want to come to with everything from their personal problems to questions about their inclusion in the team.

“Whatever my position, I like the relationship to be an amicable one, where they know they can talk to me, but I’m not their friend. Most of all, I expect very high standards of professionalism from myself and those around me. I expect the players to work hard and try hard for the team, and that’s regardless of whether they’re a top Champions League winning player or a young lad who’s just broken into the first team.”

That doesn’t mean ignoring the limitations of who you’re dealing with, he cautions, or expecting more from them than they’re currently capable of. “You have to understand their strengths and weaknesses and work with them,” he says. “So if, for example, you have a player who’s a great dribbler, it makes more sense to help them develop that skill and build on it than attempt to turn them into a great tackler.”

Irvine loves the challenge of putting on sessions that will stretch players both as a team and as individuals and has always made a point of helping those players who want to work on their game outside of group training sessions. “That has to be driven by the player, they need to come and find you, but it’s often the most satisfying coaching you get to do,” he says.

“I also have a real passion for analysing the opposition and coming up with game plans that exploit their weaknesses and reduce the effectiveness of their strengths,” he adds. “I look to create sessions that help players understand their jobs, in and out of possession. I love the small details, because that’s often where you make the biggest difference.”

Editor's Picks

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Related

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

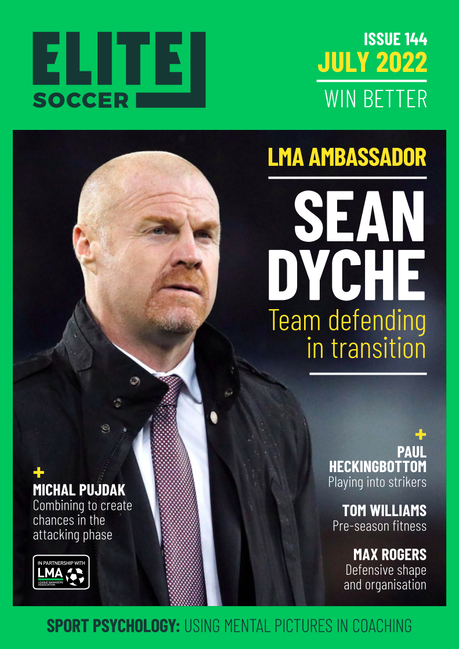

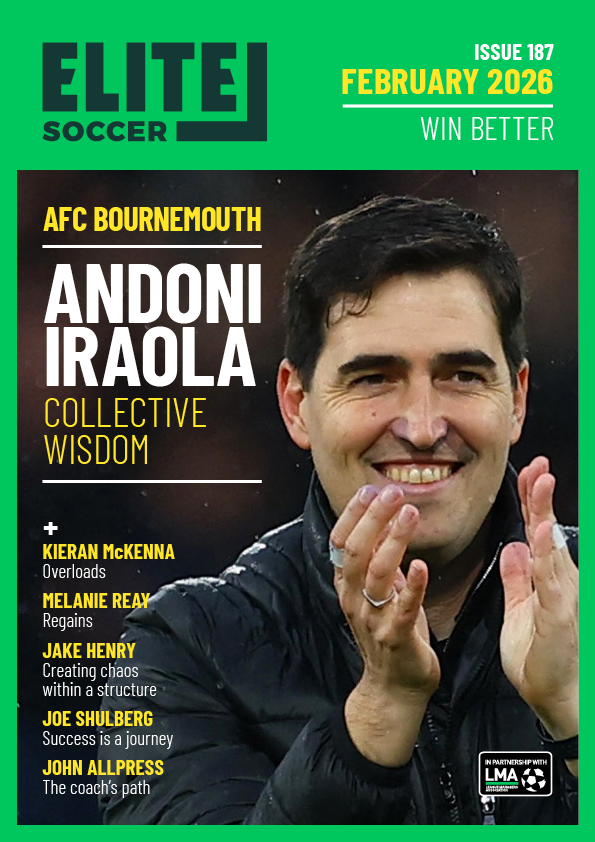

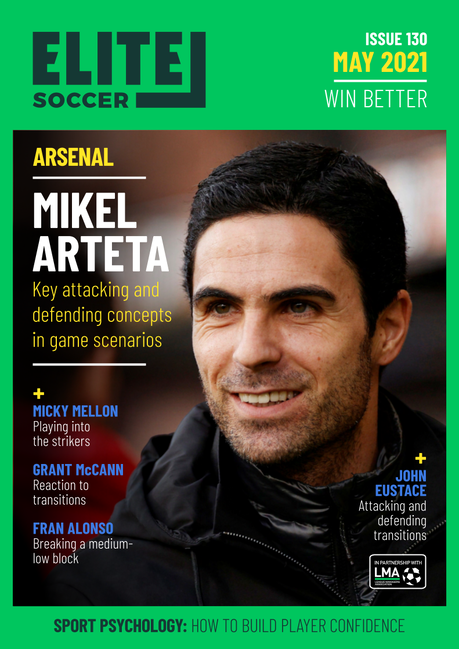

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.