NEXT ELITE SOCCER COACHING AWARD COHORT STARTS FEBRUARY 16 - ENROL NOW

You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

One man, two dugouts

Dave Robertson has more experience in the military than he does in football management, but it’s a grounding that has already proved invaluable in his fledgling career.

Having left school at 16 and failed to fulfil his dream of becoming a professional footballer, Dave Robertson followed in the footsteps of his father and grandfather and joined the Royal Marines. He never imagined it would eventually bring him full circle back into the beautiful game.

After completing 30 weeks of gruelling commando training, Robertson was presented with the coveted green beret before being drafted to everywhere from Kuwait to Norway and Guyana.

“I was very fortunate that during this time I was able to play for the Royal Marines and the Royal Navy football teams and also to complete my coaching qualifications,” he says. “It was an interesting time, because my love of football and my military career were starting to overlap in a way I hadn’t anticipated.”

However, when Robertson left the Marines in 1998 he knew it was a career in coaching that he most wanted to pursue. “Football was the one great love I had outside of the Marines, but I also knew it wouldn’t be easy and I would have to create that future for myself,” he says.

Transition

And so began a long period of determined self-improvement by the novice coach, first working his way through his coaching qualifications until he achieved the Pro Licence. Being properly qualified, he says, was essential, but if he was to become a manager one day he knew he’d also need on-the-job training. “It was important for me to find the right club, something that would present enough of a challenge and give me the experience I needed to add to my qualifications,” he says.

Taking the time to prepare properly and to understand the game, the industry and the manager’s role was key, says Robertson, especially in such a fast-changing industry. “When I look back on it now, I can see just how important it was that I built the right skill set so that when an opportunity came along I was ready for it. It also meant I was adaptable enough to move with the changes in the game,” he says. “It’s always tough when you go through transitions in your life, but I enjoy challenges and it was important for me that I owned my future success.”

Robertson’s first experience in the hot seat came at Peterborough, where he was appointed caretaker-manager and made an impressive start in the role, winning his first three games. He was given the permanent job in May 2015, but was replaced in September of the same year. Later that month he took the job of Under-21 manager at Southend United, and in November this year was appointed manager of Sligo Rovers.

“The most important thing I’ve learnt over the past 12 months is the importance of having a genuine love of the game and keeping that passion alive,” he says. “When you experience challenges it puts that love to the test and how you respond in tough times ultimately determines how successful your career will be; you have to manage things with dignity, integrity and draw on your values.”

And Robertson says he harnesses his own run-ins with knock-backs and disappointment to help his players. “Players will have peaks and troughs in their careers and you need to equip them with a strategy to cope with that,” he says. “I believe that using my own experiences in football and life I can help the players through that.”

Planning and discipline

In many ways, footballers are a world apart from the soldiers that used to make up Robertson’s team in the Marines, but their commitment to working together is equal. “They share that team dynamic – the collective understanding of what their roles and responsibilities are and how that brings success to the group,” he says. “That’s where skilful leadership and management really comes into play, because there needs to be a focus on and development of the individuals in the team, while also understanding how the team achieves success. Ultimately, in football as in the Marines you don’t win things on your own but as a group.”

He refers back daily to the skills, knowledge and experience he gained from his coaching training, but also from his time with the Marines. “The importance of planning and preparing and, most importantly, attention to detail are all skills I learned in the military that help me every day as a manager,” he says. “I always start with the end goal in mind and set out a strategy for the team to work from together. Then I focus on getting the processes right and work my way back from there. I ask, ‘what do we need to do in order to achieve our goals?’

“If there is a set of orders to be given or a mission statement to be communicated, I’ll deliver it twice, just as we did in the military, because doing so emphasises the power of the message and really brings everyone together towards that common goal,” says Robertson.

Then, of course, there’s adaptability and discipline. “When I was stationed in Kuwait it was desert warfare, in Norway it was Arctic warfare, and in Guyana it was jungle warfare, so you have to be able to adopt different strategies while holding true to yourself,” he says. “The same goes for football. It’s important that the manager and his team have enough flexibility that they can play successfully against teams with very different styles, while still maintaining their own philosophies, beliefs and values.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly for an ex-Marine, Robertson believes that high standards of discipline are a must if you want to be the best, but the emphasis is on self-discipline rather than simply following orders. “Making sure that the standards you set are acceptable, attainable and that everyone has ownership of them is important,” he says.

“The players need to buy into the standards they live and work by. I would, therefore, always encourage my players to help set their own standards, because it’s better for me to step in when necessary rather than micromanaging every situation that arises.”

Hard hats

There is also much that the modern game could learn from the military in the area of mental strength and resilience. Robertson believes that, while sport science is playing an ever-increasing role in ensuring players are in peak physical condition, psychology should also be incorporated into every training programme.

“Footballers today are supreme athletes, but for them to perform at their best in key moments of a game they need to be trained to optimise their emotional control, the way they think, their mind-sets and approaches. The best players are those who can operate with a clear mind while they are at the peak of their physical capacity.”

Footballers are not endurance athletes in the same way that Marines are (the latter will march for 30 miles at speed before taking part in military contact), but for both groups the most important thing is performing with a clear mind, following a strategy and buying into the team’s work ethic, all while experiencing the strain of fatigue.

“And that doesn’t just mean physical fatigue,” adds Robertson. “It could be the pressure of the stadium or an intimidating score-line. Players need to be able to operate at the peak of their physical fitness, but also technically and tactically with clear minds in those situations.”

“In the military, you’re rarely training when you’ve had a good night’s sleep and are feeling fresh; it’s mostly when you’re giving everything physically, when you’re exhausted and facing adversity,” he says. “That’s when people really shine and show you what they are capable of; that’s when it really matters.”

Editor's Picks

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

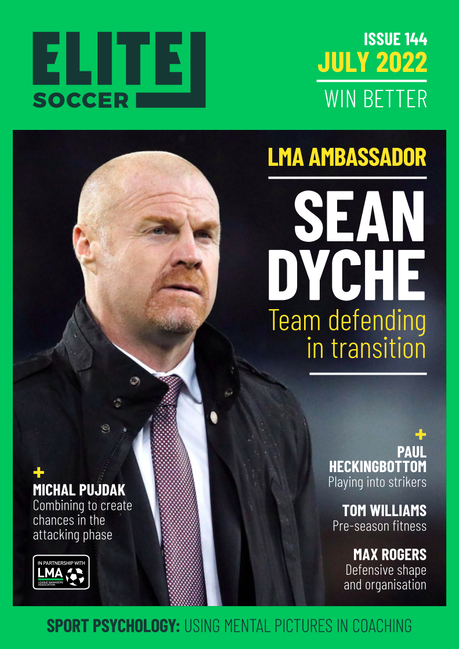

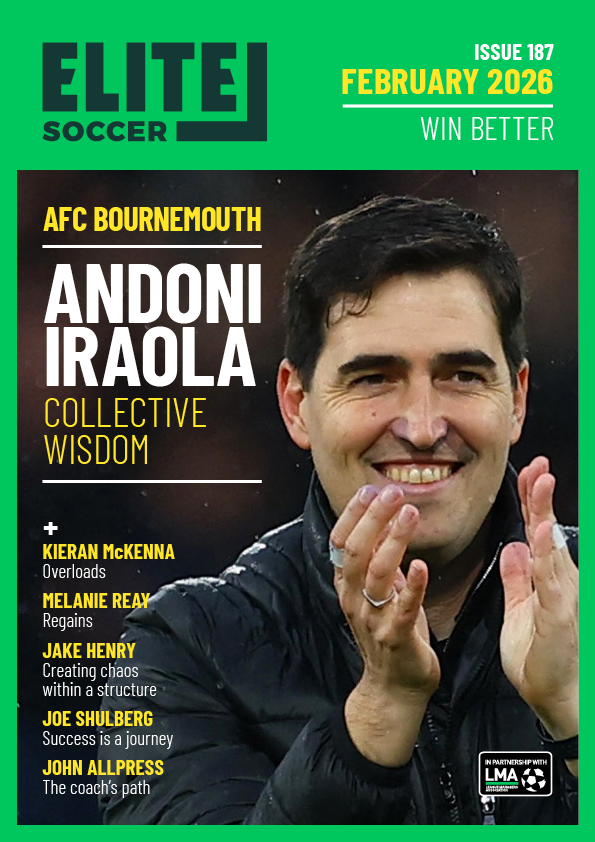

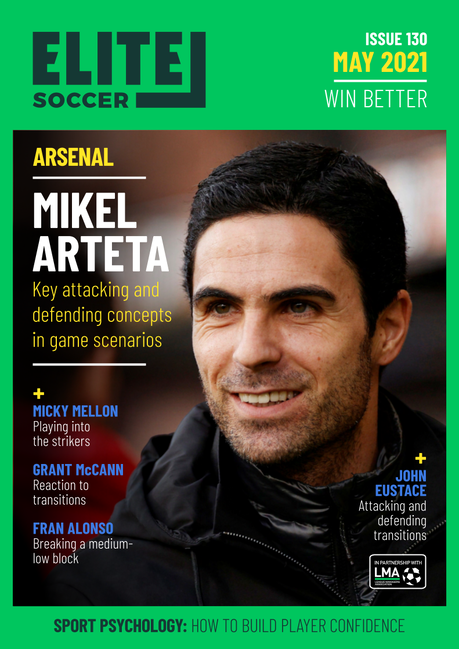

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.