You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Ben Bartlett's principles of practice design

Ben Bartlett, Director of Methodology at Houston Dynamo, shares his approach to developing a game model through practice design

Our coaching sessions are likely to be increasingly impactful when they clearly reflect the type of team we aspire to be. This can shift our focus from generic practices, or copying and pasting from other coaches, to an approach that aligns with our game model.

Whilst game models can sometimes be interpreted as fixed, rigid and rules based – for example, we build attacks with three players in deep positions – I continue to highlight the importance of them being seen as flexible frameworks that both players and coaches can make decisions within and, as a consequence, vary those decisions dependent on the circumstances.

Similarly, the coaching sessions that enable the development of our game model are better shaped by principles of practice design and training components rather than core practices or playbooks that all coaches in a club are mandated to deliver.

My personal belief is that core practices and playbooks erode coaching expertise. This belief is grounded in the idea that such core practice recipes are good for simple tasks, like baking a cake, although less useful for complex tasks like player and coach development, which are unlikely to be suited to a set of specific instructions.

Training components

However, often, the only thing human beings dislike more than rules are no rules. Hence, over time, I have committed to supporting coaches with principles and ingredients, rather than rules and recipes.

There are three training components, or practice types, that embody that commitment:

1. Activation

Practices that enable the players to prepare physically for the intended demands of the session. This physical preparation is blended with our game model.

2. Small-numbered games

Practices that enable fewer relationships and connections. These can be anything from one to six players on each or either team, for example 2v2, 3v2 or 5v5.

3. Large-numbered games

Practices that enable greater numbers of relationships and connections. These can be anything from seven players on each team.

The examples on the following pages illustrate how these training components can be used to structure practices. The whole pitch is used for each component, but area sizes differ for each practice in order to achieve different outcomes – varying between big, small, wide and narrow areas.

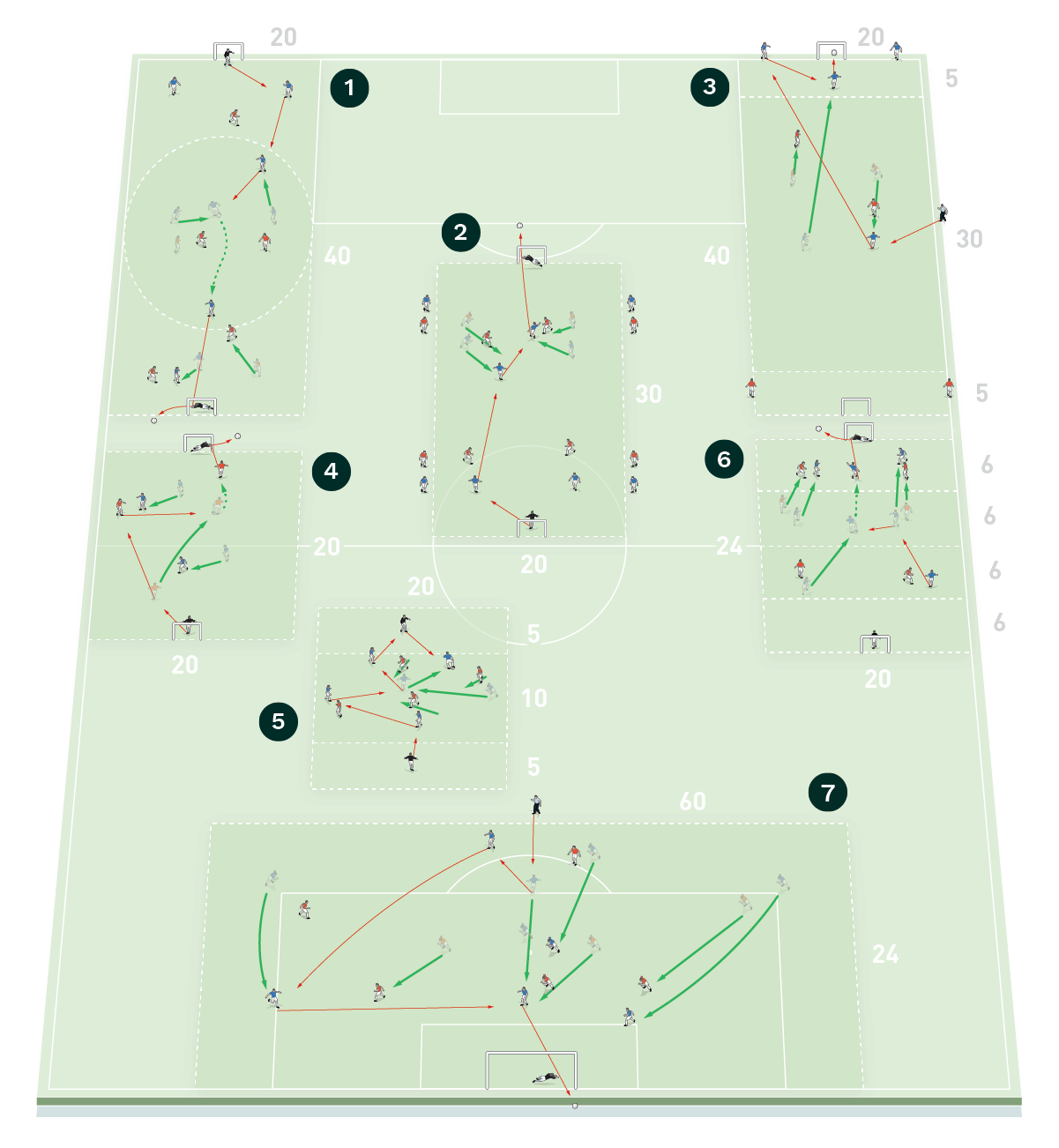

Activation

1. 5v3

- The red team are our deepest five

- The blue team are our most advanced five

- Three players go to press

- Score by achieving ten passes or bouncing the ball out and scoring in a mini goal

- Committing a foul awards a goal to the other team

2. 9v7 build and counter

- The blue team work the ball end to end to score

- The red team regain the ball and score in either goal

- Players are locked into zones

3. Tight area 4v4+3

- Score by scoring in one of the mini goals

- The first team to three goals wins

- Set up formations to enable build and press solutions

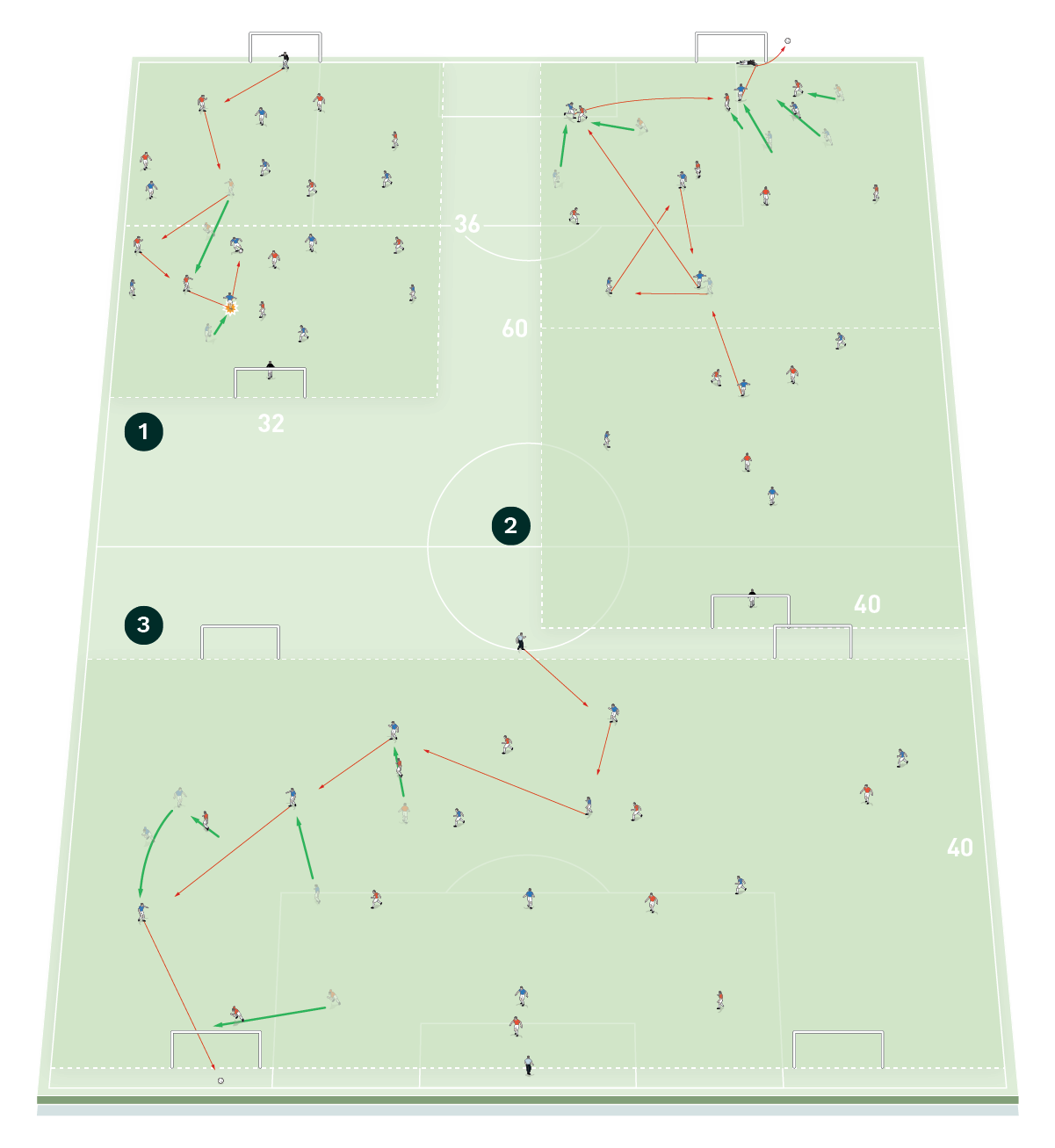

Small numbered games

1. 6v6

- Start the build outside of the circle

- Score inside the circle

- Freedom of movement

2. 5v5+4

- Score a goal to stay on the pitch

- Use the players on the outside

3. 2v2+2

- Position the end players to the side for the red team and at the end for the blue team

- Play into the end area

- Run into the end area to receive the ball back and score

4. 3v3

- Combine to score

- Play on different lines

5. 5v5

- Round the corner

- Give and gos

- Must combine before playing to the end

- The longest uninterrupted sequence wins

6. 5v5

- Players locked into zones when out of possession

- Use bounce passes to create 3v2 situations

- Score in the mini goals

7. 5v5

- Final third concepts

- The defending team look to keep a clean sheet

- Each team gets ten balls

- The cleanest sheet wins

Large-numbered games

1. 11v11 tight

- No tackles permitted

2. 11v11 medium

- A goal counts for the number of passes completed in the opposition half in the run up to scoring

3. 11v11 wide

- Provides an opportunity for prolonged defending and attacking

- Play for 12 minutes

- Both teams aim to keep a clean sheet

- Use match ups and rivalries to generate competition

Small-numbered and large-numbered games can be used, in different ways, to address an aim. The two examples which enable players and teams to, in combination:

- Focus on building up and progressing through pressure to score goals

- Be intense and purposeful in winning the ball back so they can practice using the ball to start attacks and score goals.

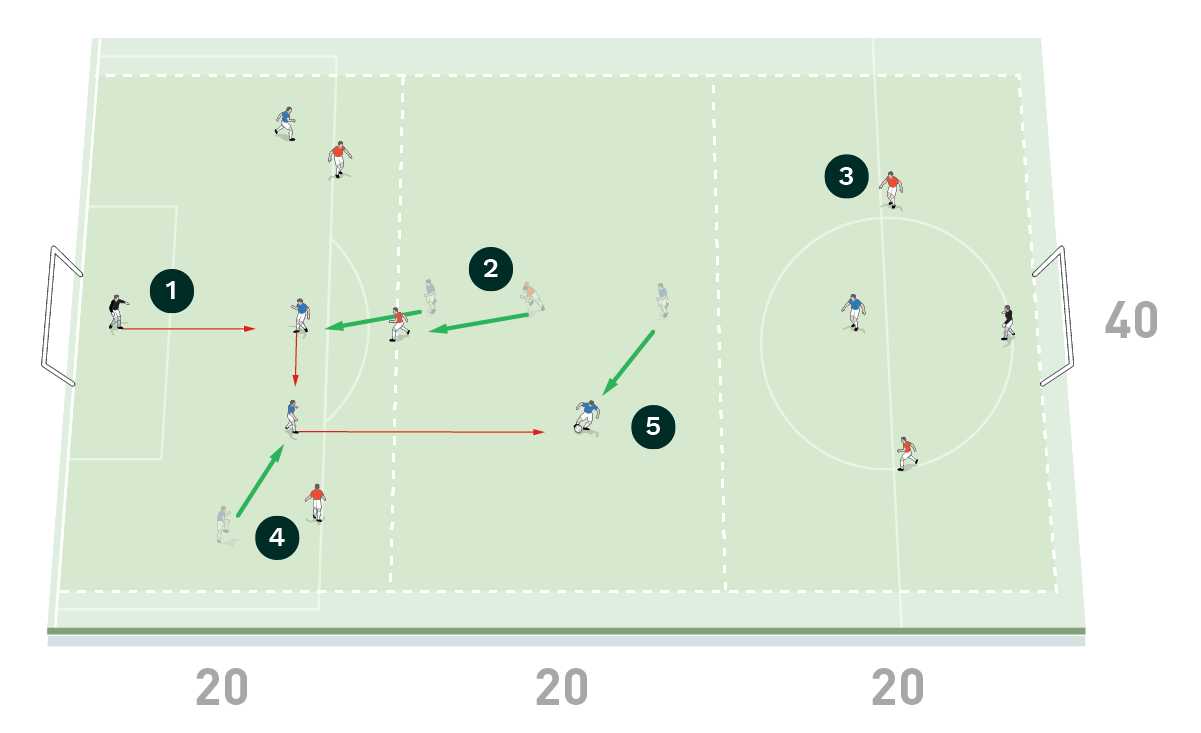

Small-numbered game

The small-numbered game challenges players to either build up through pressure or play longer passes beyond it. The practice is conditioned such that the first pass played by the goalkeeper can’t be played into the middle third.

This can sometimes be critiqued as being unrealistic. However, by eliminating some decisions for players, we place a focus on the opportunity to, more frequently, practice and get better at others. In this instance, it supports low players to practice receiving under pressure and using bounce passes or rolling with the ball to escape that pressure.

The blue team play a 2-2-1, providing opportunity for a deep midfielder to drop into the defensive line to support the build-up (against the two red forwards) and for an advanced midfielder to move into advanced positions to receive longer passes and support the central forward.

Once the first pass is played by the goalkeeper, the condition is spent, consequently enabling the advanced players to move into the space created in the middle third to support the lower players to build up.

Restricting some decisions while leaving the players with multiple choices constrains players to focus on certain ways of playing and to play under the increased pressure generated by that restriction.

- The first pass from the goalkeeper cannot be played into the middle third

- Teams can play into and through pressure, drawing the opposition onto them

- Red team set up in a 2-1-2 formation

- Blue team set up in a 2-2-1 formation

- Teams can play past pressure, going straight into the attacking third

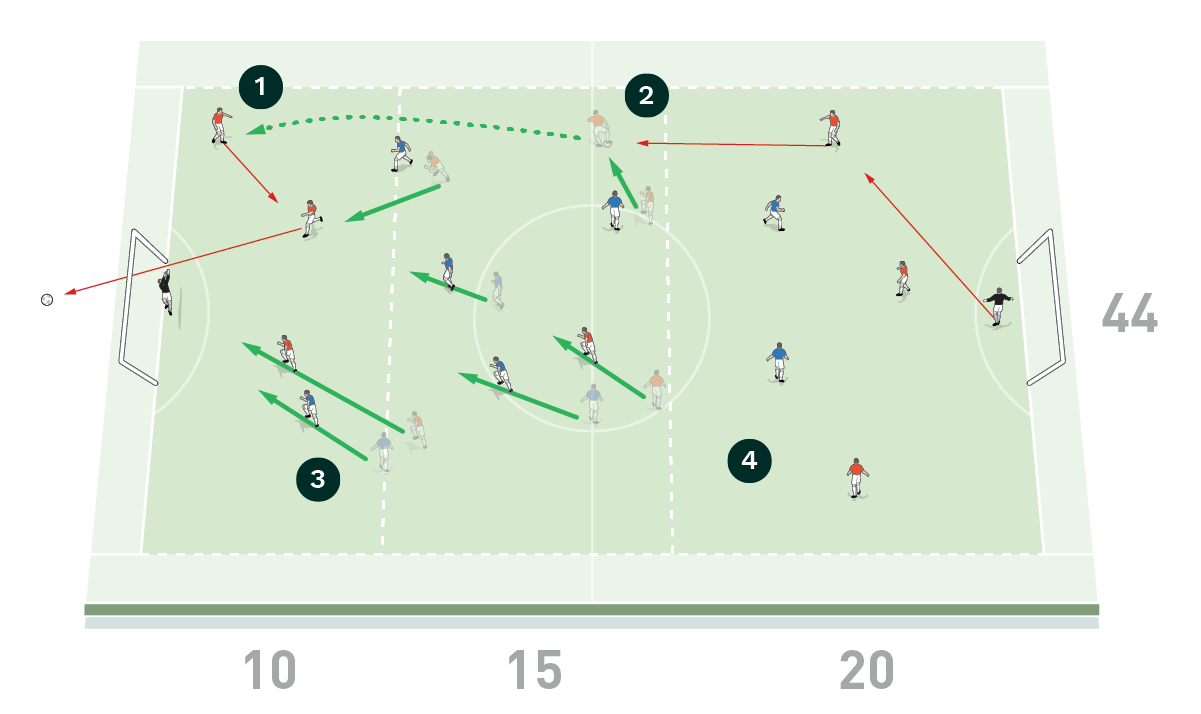

Large-numbered game

The large-numbered game is an 8v8, which provides a greater reflection of certain 11v11 systems of play.

The red team play in a 3-2-2 to reflect the 3-box-3 formation which is popular here at Houston Dynamo, while the blues play a 2-3-2 to reflect aspects of the 4-diamond-2 that one of our teams uses.

This retains the focus on building up and progressing through central areas and also places a restriction within a certain part of the pitch. This restriction, strategically, intends to support players and teams to practice playing quickly and speeding the game up. Changes of speed are good for destabilising the opposition.

In the slightly offset central area, players must release the ball one touch. This forces players to combine centrally through this area to access higher areas where goals can be scored. It also supports players to play slower in the first part of the build-up (in the deeper areas outside of the central zone) and go quicker as they progress. A one-touch combo resulting in a goal counts for two.

The blue team focus on those changes of speed in lower positions (nearer their goal) while the red team do so nearer the opposition’s goal.

There is one caveat: the restriction only relates to when players release, i.e pass or shoot. If they receive in that offset area they can travel with the ball through and out of the area and then pass or shoot from the advanced areas.

Like the small-numbered game, this constrains players to practice specific aspects of our game model – combining centrally and changing the speed of play – while enabling players who are good at and like to dribble and beat opponents to work on doing this.

This concept is what academics refer to as ‘constrain to afford’. We constrain certain decisions (either by field size or practice conditions) to afford the players the opportunity to practice others.

- Speed of play is encouraged through this restricted area: miss it out, combine quickly or dribble out through it

- If releasing in this area it must be one touch

- Blue team set up in a 2-3-2 formation

- Red team set up in a 3-2-2 formation

Consider your game model, the players learning to play within it, and seek to design sessions and experiences that deepen the players’ and the team’s skills in relation to the kind of team you want to be.

Related Files

Editor's Picks

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Pressing principles

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.