You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Rousing, responsive and resilient

Elite Soccer’s Ben Bartlett on how to move beyond a binary approach to coaching, allowing us to connect what’s important in our context to the nature of the players in our care

The general nature of the concept of intentional learning for coaches often seeks to divide and constrain us to binary choices. Two examples follow; the first related to style of play, the second to how we might support players to learn how to play.

- Should I be a coach who coaches positional play or one who focuses on what is now referred to as ‘relational’ football?

- Do I work from an information processing perspective (where players are taught pre-defined moves and language that they can draw from memory) or support an ecological approach to learning where solutions to problems emerge from individuals’ interactions with the environment?

If we choose one or the other, we wed ourselves to a particular way of doing things. If we stand in the middle of the road, we likely get run over in both directions.

These narratives can also imply that we can only choose from the narrow menu that’s in front of us, or that we are controlled by currently accepted perspectives.

Whilst creativity can often be said to require a framework to support its’ emergence – the game itself and the people playing it might be better considered as frameworks to guide both player and coach decisions, rather than arbitrary popularised, and often polarising, positions.

This could be viewed as a constraints-led approach to coach and player development; enabling a person to take a focused, flexible and responsive approach to human development and, ultimately, soccer. Seeking to coach soccer through this lighter footprint can ensure that we don’t co-habit a conventional corridor. Instead, we can explore a broader, wilder territory, ensuring that alignment is not achieved by everyone mirroring the same template, but by supporting nations, clubs, coaches and players to navigate today, whilst futureproofing for sustainability and environmental resilience.

Focusing attention and learning towards better understanding the game and the human beings playing it as a means to consider playing and coaching soccer can free us – and, more importantly, the players – from rigid rule-based, routine and rote replication. That’s to say replicating playing and coaching soccer like someone else, or repeating specific moves and patterns that players are taught to rerun.

Connecting what’s important in our context to the nature of the players in our care becomes the unique landscape that we navigate. Systems of play, specific principles and sub-principles, standardised player profiles and core practices become redundant and irrelevant in environments guided by a more responsive approach to learning to play soccer.

For the purpose of advancing this perspective, I encourage you to consider playing soccer and supporting player development in ways that are rousing, responsive and resilient, such that we can win games and support player development. Rousing refers to the capacity to elicit positive emotion from the people playing and watching the game. Responsive means responding in ways that take account of our ever-deepening understanding of the people in our care (and the opposition we compete against). That rousing and responsive approach to playing football should be resilient across time, when the competitive temperature dials up and when the opposition adapt to what they believe they know about us.

As outlined at the outset, we can often feel the pressure to choose. We choose to win, we choose to develop or we choose to play aesthetically pleasing football. In choosing, we often feel it’s necessary to compromise one or more of the others. But perhaps we can commit to all of them, connected together.

“Connecting what’s important in our context to the nature of the players in our care becomes the unique landscape that we navigate”

Playing football

The narrative surrounding relational or positional play is, mostly, unhelpful. It’s as if relational and positional play are churches to worship. If understanding the players and the important factors within our context are what we believe is important, narrowing ourselves to a specific religion of the game may be inhibiting.

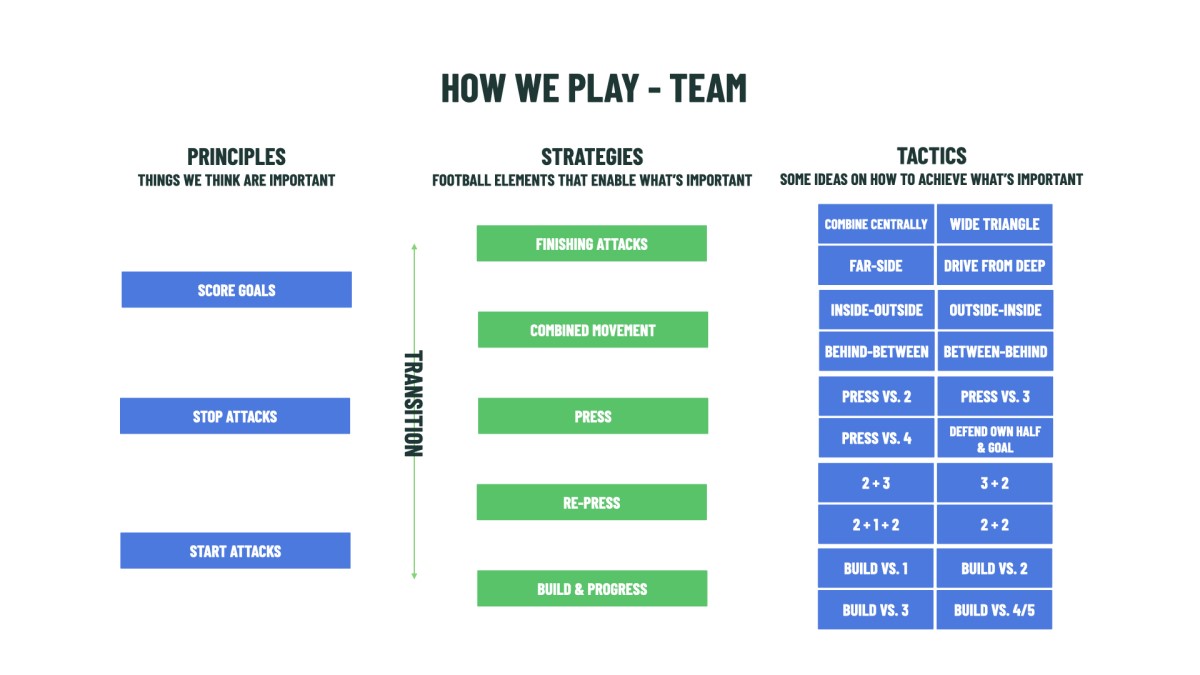

The below are some ways of considering the game:

- Principles - Moments that are important in the game of football

- Strategies - Team interactions that can help the team and players navigate those moments

- Tactics - More specific ideas that might help us start attacks, stop attacks and score goals.

In the Elite Soccer Coaching Award preview learning hub, you can access some footage of how the four finishing attacks tactics in Figure 1 may look in the game of football.

It’s important to highlight:

- Transition is a part of each of the three key principles and is an important skill for players to learn to manage, both individually and as part of a team. It is intended to be considered within each of the principles directly such that we consider transitioning to be able to score goals, manage the ball and the game in starting attacks, and prevent opponents scoring in transition.

- Classifying the game into specific strategies and tactics can be perceived as contradictory to the idea of playing fluid, flexible and exciting football. It is intended to be a commitment to helping bridge the movement towards supporting players to play the game in more connected, ever-changing ways.

- The more specific tactics demonstrate that the game can still be perceived with some semblance of structure without it becoming fixed or immovable. In the case of finishing attack tactics, players and teams can and do, as seen in the videos, seamlessly blend these tactics such that, as an example, the wide triangle can be used to draw the opposition onto one side of the pitch (into what can be perceived as relational by enthusiasts of that particular preference) to enable the team and players to combine through central areas or threaten the far-side of the pitch.

- Players learning the timing, movement and awareness of space – both with and without the ball – to be able to adapt and respond to the game as it changes is ‘the curriculum’ (not, for example, routinely learning how to only ‘Press vs. 2’).

“The more deeply aware we are of the human beings in our care, inevitably, the more we are able to interact with them, coach them and support their development”

Flexible frameworks of this nature have been useful for me in multiple professional roles, supporting clubs, teams, players and coaches to develop rousing approaches to playing the game while ensuring significant degrees of freedom for players and coaches to express their own unique brilliance. Such thinking frees us from the shackles of positional profiles (often exemplified by stating the specific things a number ‘10’ should do, for example) and the sometimes-limiting nature of promoters of positional play, where players occupy arbitrary lanes on a pitch.

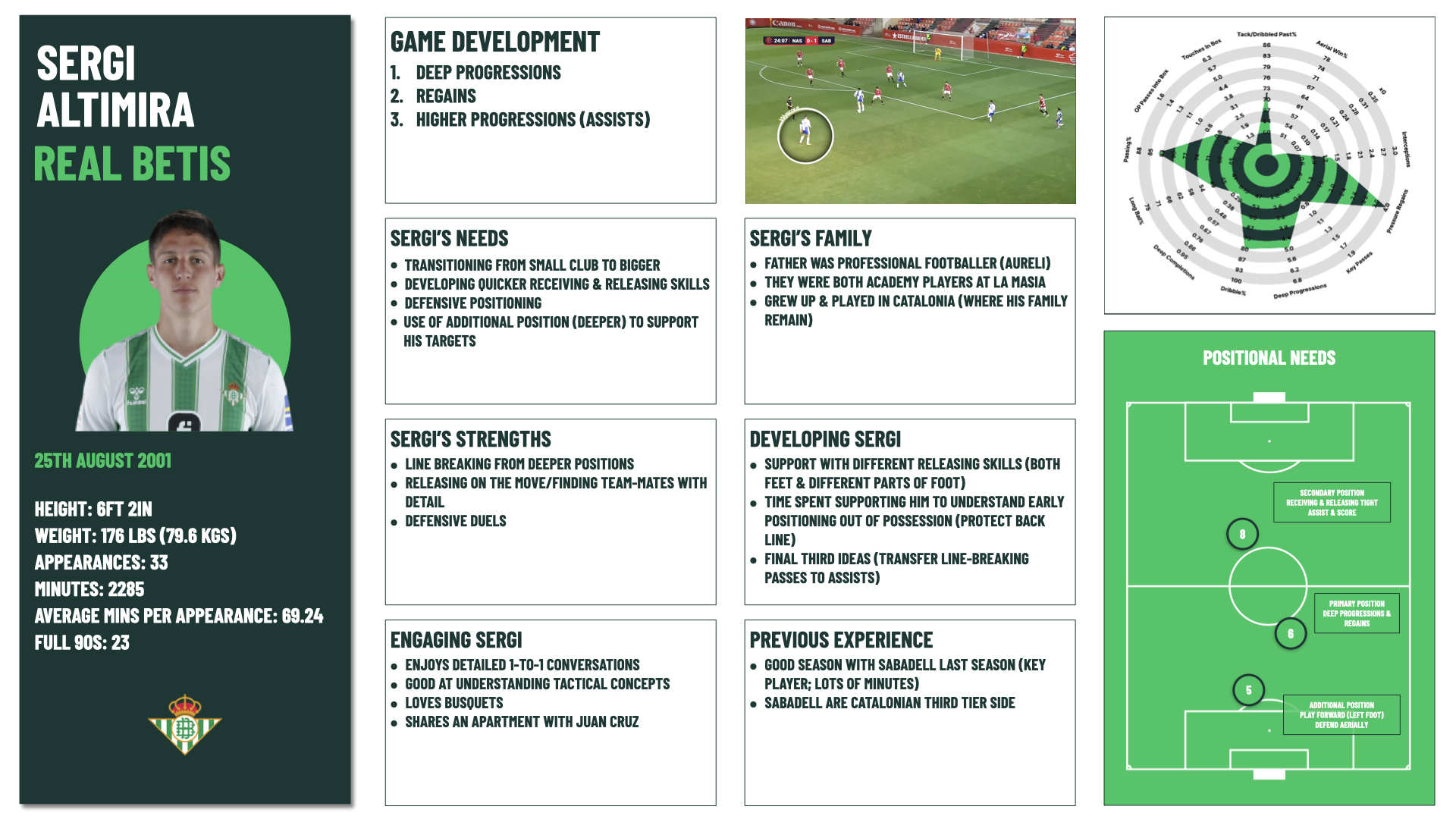

Profiling the players as they are and reflecting what we’ve come to understand about them is a rich investment of our energy. The more deeply aware we are of the human beings in our care, inevitably, the more able we are to interact with them, coach them and support their development in ways that are responsive to the person that they currently are and intend, aspire and have the potential to be.

Figure 2 is an example of how we might embody this thinking such that the shape and size of our coaching sessions and game-day interactions are continually influenced by the nature of the players.

Related Files

Profiling players in these ways supports us to synthesise:

- The elements of their game and nature that are important to their on-going development

- Things that they need (as well things they might like)

- Data and video of how they have been getting on such that we continue to track, longitudinally, how they are doing, supporting us to adapt our approaches as people, inevitably, change

- Measuring opportunity. How many minutes are they playing, for how long at a time and on what parts of the pitch? It’s difficult to get better at things if the environment doesn’t afford us the opportunity to practise them.

This can then guide us towards our approach to practice design, enabling the team and the players to develop team principles in unison with their individual needs.

Approach to practice design

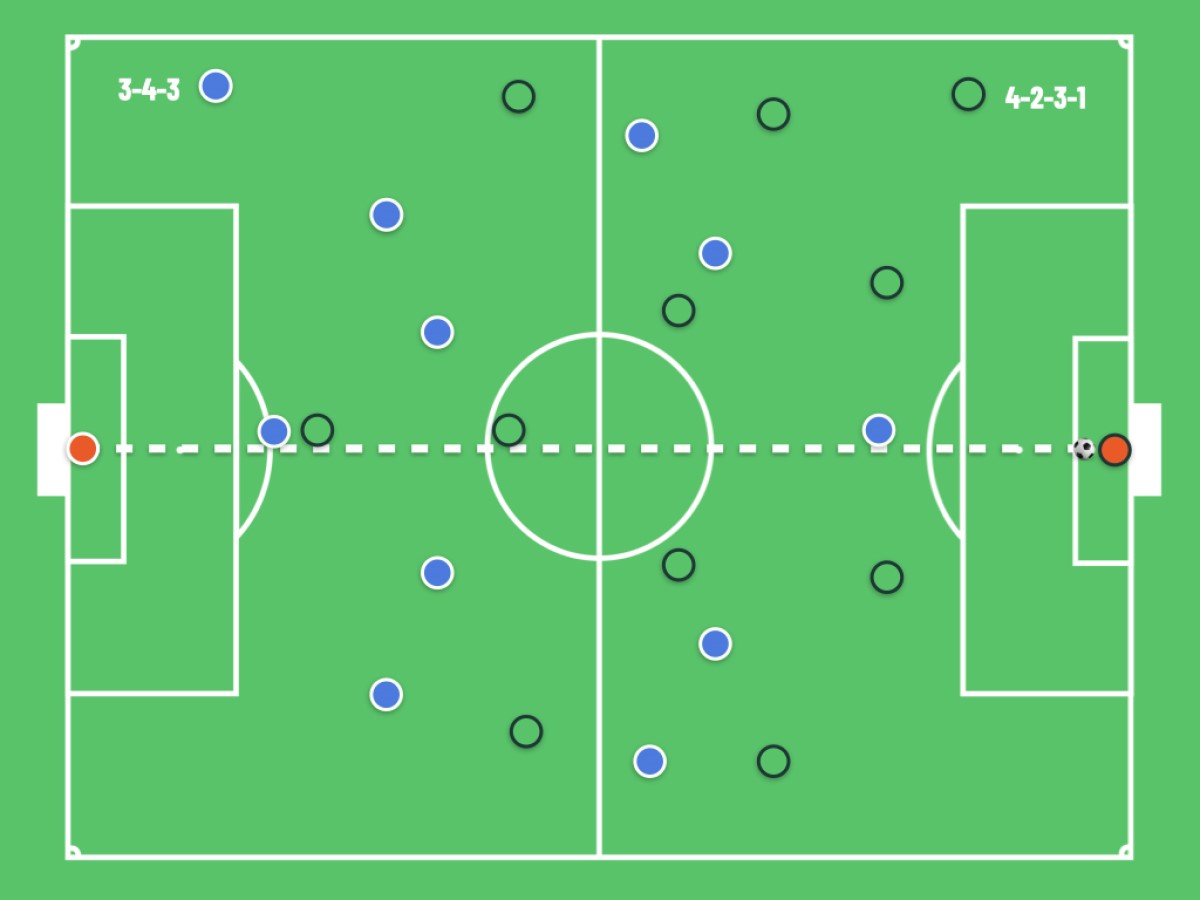

An example session is illustrated in Figure 3. It’s an 11 v 11 game with teams organised into two different playing formations, each coached by a different coach. The game can be played on different sized pitches dependent upon space limitations, aspirations for whether we would like players to play with greater or less space available, or weekly periodisation principles.

The game is set up with a vertical line through the middle of the pitch to guide players decisions, not restrict them. The traditional halfway line and penalty areas are also evident. Because this is a game with one ball, two teams and two goals, all of the playing principles highlighted earlier in this article are present. However, the ways we constrain the game, organise and coach the players, supports certain aspects of the game to be more prevalent than others.

The game has one task constraint: crossing the vertical line in possession and scoring results in two goals. Instinctively, this can focus attention on switching play. Although, if we view the task constraint more broadly, it enables the team out of possession to seek to lock the opposition to one side (to prevent the other team gaining greater reward) and constrain the team in possession to seek to, perhaps, utilise finishing attack ideas (identified in Figures 4a, 4b and 4c) like central combinations, wide triangles and driving from deep to create chances when the opposition are compact.

Figure 4a. Wide triangle

Figure 4b. Combine centrally

Figure 4c. Drive from deep

As coaches, ensuring the playing principles from our framework are always ‘in the water’ of our sessions, reduces the need to ‘inject’ players with lots of information during stoppages in sessions as these ideas are continually washing over the players.

This can support us to highlight ideas, encourage them and praise their progress across multiple events, rather than feeling the pressure for certain things to happen at once.

These ideas are not ‘mental models’ that the players run or have to process before executing, or things that we ask them to regurgitate back to us verbatim to demonstrate what they have learned. Rather they are just opportunities for players to act; shaped by their own interactions with what is going on in the game at any given moment.

This enables us to position players, like the profile of Sergi Altimira illustrated in this article, in any or multiple midfield positions throughout the session, even swapping teams if desired. In the example of Altimira, this would support him to practice his deep and advanced progressions through his interactions with both his teammates and the ways the opposition defend.

If we would like an increase in lower, deep progressions from some players or a team; enabling that team’s goalkeeper to start the game more frequently can enhance that frequency. If we would like to increase and practise more advanced progressions, we could perhaps play 11 v 10, such that the team of 11 have more of the ball, higher up the pitch against a team learning to defend resolutely near their goal.

Our players, within our agreed playing principles, contending with the opposition who are trying to stop us, is a ‘constraints-led approach’ to coaching. This is an approach that supports us to develop the rousing, responsive and resilient approach to football and player development that can illuminate our collective futures.

“Ensuring the playing principles from our framework are always ‘in the water’ of our sessions reduces the need to ‘inject’ players with lots of information during stoppages in sessions as these ideas are continually washing over the players”

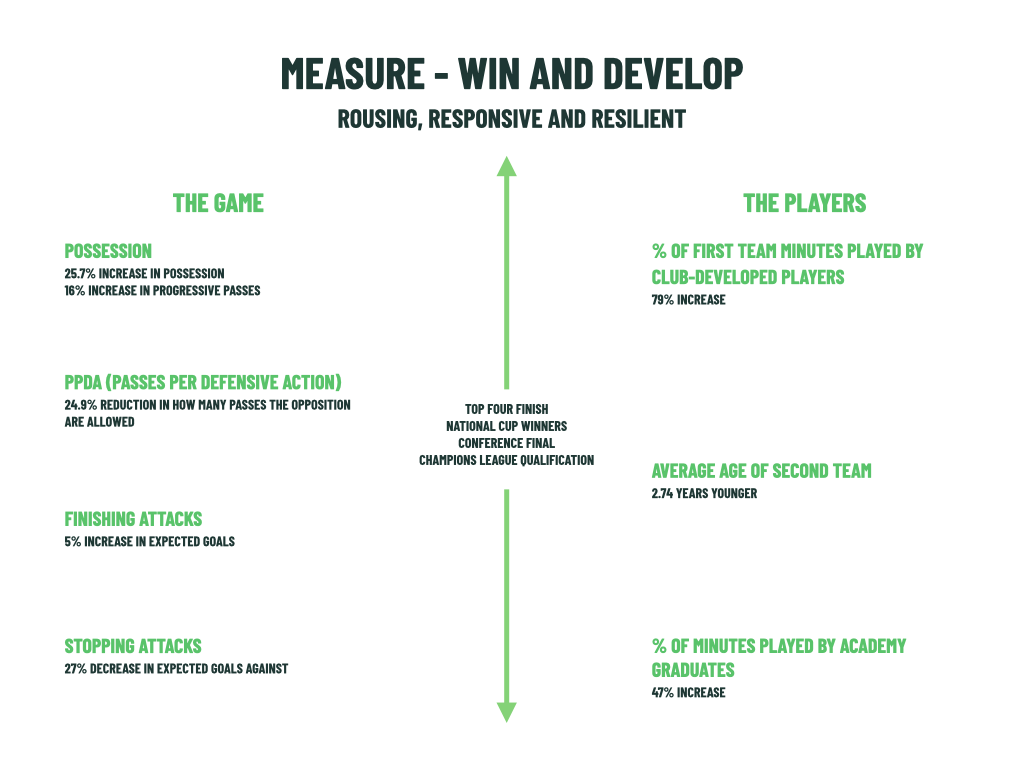

Measurement

Finally, the aspects navigated through this article are the things we measure. This can support us to check how we, as coaches, are getting on, principally in the same way we check how the players are getting on.

We should measure how we play and focus on opportunity as a metric. Some of the ways we have reflected on the progress of the team and players in a club environment I have worked in across a two-season period are illustrated in Figure 5.

This places a laser focus on measuring the things we value and enables a club to consider winning from a variety of perspectives: win games, win in progressing the nature of the way soccer is played in your local and more global environment, and win in supporting player development.

It also highlights where progress has been less evident, ensuring we continually refine our playing, player development and coaching processes to support further progress and future commitments.

That might just be learning: not necessarily what we remember, more how we are remembered.

Editor's Picks

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Pressing principles

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.