NEXT ELITE SOCCER COACHING AWARD COHORT STARTS FEBRUARY 16 - ENROL NOW

Player motivation

Sport psychologist Dan Abrahams examines the different reasons that motivate players to compete

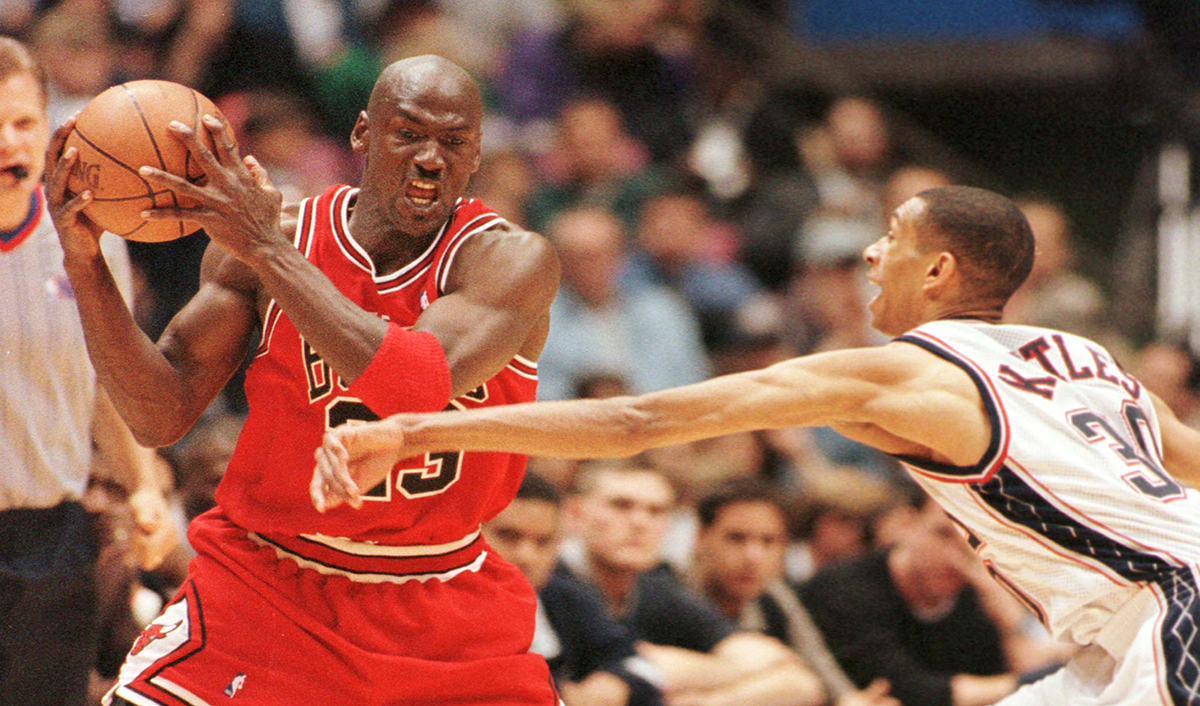

Netflix documentary, ‘The Last Dance’, proved compelling viewing for most sports competitors and coaches. Unofficially declared as the greatest sports documentary of all time, it gave us an incredible insight into the great Chicago Bulls basketball team of the 1990s.

Whilst sports documentaries don’t necessarily offer viewers precise details of events, nor always an honest account of proceedings, this thrilling watch did provide us with an insight into quite a few important coaching topics. I loved learning about Phil Jackson’s psycho-social approach to coaching, particularly the way he handled individual differences in temperament. Equally fascinating was the coverage of those famous Michael Jordan performances, brilliantly accompanied by Jordan’s explanations for his ability to raise his game to a higher level when he needed to.

The programme left us in no doubt as to the athleticism of Jordan, but it also lifted the lid on his brutal, unrelenting competitiveness. He talked about the influence of his father, his yearning to get the most from the talent bestowed on him, as well as his unyielding will to win titles.

Of course, not everyone has Michael Jordan’s single-minded focus on winning. Clearly very few sportsmen or women enjoy his natural athleticism, but perhaps just as few are moved as strongly as he was by the will to win, and by the will to beat others.

But does that really matter? And what can coaches do about that anomaly?

THE MOTIVATION TO COMPETE

As a sport psychologist I find the motivation to compete fascinating. I’ve learned over the years that motivation truly is a complex and very individual subject. I think at the very elite level of sport, we’re a little presumptuous that the will to win and the will to beat others are the twin engines that drive a player’s desire and ability to compete. We’re also perhaps a little quick to think that an absence of these engines renders players less likely to produce consistently high performances.

This is a very narrow view of motivation. Many players will execute high intensity runs in those last lung busting five minutes for reasons other than the will to win. And many players will run the length of the pitch because they’re motivated by something other than the desire to beat others.

To explain, let’s consider motivation as falling along a vertical line from extrinsic (external rewards) to intrinsic (internal drivers).

At the very top of the line lie the external rewards I’ve spoken about above: the will to win and the will to perform better than others. With ‘winning’ and ‘outperforming others’ come rewards such as titles, money, fame, and adulation.

I couldn’t imagine a sporting world where this kind of extrinsic motivation doesn’t exist, and where external rewards don’t motivate most (if not all) competitors. They do! And as a sport psychologist I’d never look to extinguish or dampen these sources of motivation. But there are a couple of problems. Firstly, and as mentioned, whilst everyone would like to win, not everyone experiences the burning ambition that Michael Jordan possessed. Secondly, this form of motivation can come burdened by psycho-social problems.

For many (but not all), being extrinsically motivated alone can cause the onset of anxiety and stress, a fragile sense of confidence, a negative mood, burnout and injury, a drop in well-being, and a general lack of enjoyment. They can cause teamship and relationship problems – a lack of communication and poor cooperation. They can even be to the detriment of performance, as players who try too hard to win and too hard to high perform can play a brand of tight and tense football that prevents them playing on the front foot with freedom and focus.

Ultimately, winning cannot be controlled. Elite sports competitors may be in the business of winning, but, somewhat paradoxically, players with the singular motivation to win risk any of the above psycho-social problems, which can lessen their chances of being a winner.

INTRINSIC MOTIVATION

In contrast, intrinsic motivation can heighten opportunities to win, in a safer, healthier way. Tapping into internal drivers can liberate many footballers. It can set them free. And intrinsic motivation happens to be where many players are motivated most.

Intrinsic motivation runs from its deepest roots – enjoyment and experience, through mastery and challenge, right up to relatedness and cooperation. Let’s explore this a little further…

- Enjoyment and experience: footballers take up the game more often than not because they loved to play football as children. It wasn’t just their hobby, it was their passion. They loved the experience of having a ball at their feet, running and moving, taking players on, heading, shooting and tackling. And that’s how many of them became good enough to play professionally, from the endless hours spent honing their footballing craft.

Yes, we want to win! Yes, professional football clubs exist to win! But a mind attuned to a win at all costs mentality can soon diminish the passion a player feels for the game. Losing a love for football can weaken performance, more so than a false will to win can strengthen performance.

Over the past few years, as a sport psychologist I’ve worked with a number of demotivated Premier League players to help them get back to their deepest sense of motivation. I’ve helped them set game day objectives around the enjoyment of playing as an individual and as a team mate. We haven’t ignored the importance of high intensity runs and the crucial responsibilities they have to execute. But we’ve linked key performance indicators (KPI’s) to the enjoyable sensations of playing the game – performance will be optimised by loving the experience of running, moving, and executing football actions.

- Mastery and challenge: some players have a ‘rage to master’ more so than they do a desire to win. They yearn to execute the responsibilities in their role with distinction more so than beating the opposition (after all, if their execution is outstanding they’re going to make it tough for their opponents anyway).

When I work with players who are driven by mastery I want to help them break their game down into mini controllable tasks that they can focus on (perhaps obsess over) in the lead up to a game. I want a centre back who has this kind of ‘mastery mindset’ to pick two or three tasks that he or she is going to commit to performing with distinction. I help players place these mastery goals at the forefront of their mind going into the game, and help them to set the execution of these tasks as their main game objectives. The performance will take care of itself, and their influence on all outcomes will be positive as a consequence.

- Relatedness and cooperation: I recently spoke to a former Olympic rower who said to me that when she was racing, and felt she had nothing left inside of her – when she was willing to stop because she was exhausted – she wouldn’t let herself quit because of the presence of her team mates in the boat. She would choose to row through the pain because she didn’t want to let them down.

Some players are motivated for social reasons. Being part of a team motivates them. They have a social identity that drives their ‘why’: “I’m a part of this team and I will leave the pitch exhausted for this team. I will give it my all for my team mates.”

Working with these players, I try to help them identify what it is they enjoy most about being in a team, who it is that influences these feelings of togetherness, and who are the team mates they feel the most loyal to. I want them to understand their social drivers so they can continue to feel motivated by others in their team.

Key for coaches is to consider that different players are motivated in different ways. It’s important to be mindful of this because not everyone will respond optimally to messages of winning and talk of high performance. Consider how each of your players is motivated. Try to engage them in a conversation about motivation. Give them psychological safety to express what really motivates them, then use their answer to help them thrive and flourish on the pitch.

Editor's Picks

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Related

Pre-season fitness plan

Play around to play through

Free-kick routines

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.