You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Psychological safety

Sport psychologist Dan Abrahams discusses how creating a psychologically safe environment can help to get the best out of an elite player

Back in the late 1990s Harvard Professor, Amy Edmondson, stumbled across a pretty remarkable finding, one that still influences the leadership decisions of huge companies today. Over two decades ago, Edmondson, a professor of leadership and management, was predominantly working in medical facilities investigating human-related medication errors in hospitals. She sought to find out whether better care teams made fewer mistakes. However, she stumbled on something peculiar – that the very best performing care teams she was studying were making mistakes. Lots of them!

But here’s the twist. Those high performing care teams weren’t making more mistakes than poorer performing teams. Simply, the individuals within the best teams were owning up to their mistakes. They were actually talking about mistakes during meetings. They were discussing mistakes in detail. Mistakes were reported rather than covered up or ignored. In the high performing teams, mistakes weren’t frowned upon, they were seen as an opportunity to examine better and to discuss what better looked like. In the high performing teams, human vulnerability was embraced and normalised.

As a result of this research, Edmondson coined the term ‘Psychological Safety’. She defined it as “…a belief that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns or mistakes.” And over the past two decades research has continued to support the notion that for a team to thrive, the presence of this psychological quality is important.

However, giving players the space to express vulnerability and to discuss mistakes in professional football can be pretty scary. Will these types of conversations diminish player confidence? Doesn’t negativity simply breed negativity?

OPENING UP

Let’s examine this a little closer. Vulnerability in professional football can take several forms. It might relate to a player speaking up in a team meeting to propose an idea for a game model. It could refer to a player disagreeing with a coaching point or offering a different kind of solution to a problem. Or it might include a player admitting a sense of anxiety, worry, doubt or fear about an upcoming game, discussing mistakes made on or off the pitch, or opening up about a challenging situation he or she is dealing with.

That sounds like a lot of negative emotion, right?

But consider what you as coaches really want from your players on game day.

You want players to compete with freedom rather than fear. You want them to play on the front foot rather than the back foot. You want them to play ‘to win’ rather than playing ‘not to lose’. You want them action-oriented rather than anxious. You want them to compete with intensity rather than with lethargy. You want them proactive rather than passive. You want them supporting each other rather than isolating themselves.

By giving players space to express vulnerabilities around negative emotions such as anxiety and fear, you give them a better opportunity to play with freedom and on the front foot. You give them a

better chance to be action-oriented and proactive.

FEELING SAFE

How does this work? I believe in several ways. Firstly, a platform to share can help players to feel safer in an elite environment that’s both unpredictable and uncontrollable. Secondly, conversation around anxieties such as “I think this is going to be a really tough game this weekend” or “I’ve been playing poor recently and have dropped in confidence” can help clear a player’s mind. Thirdly, discussing personal challenges gives opportunities for team mates to problem solve and arrive at solutions together.

Of course, many of you reading this may be thinking that the expression of vulnerability in an elite sporting environment is an unrealistic proposition. I can hear the protests now: “There’s no way players are going

to be honest about their vulnerabilities. Not to coaches. They’ve got too much to lose.”

Certainly, this is a challenge that exists but, with

a little thought and careful planning, it’s one that

isn’t unsurmountable.

Clubs can use a designated member of staff to facilitate meetings where players can share, discuss and solution-find. Individually or in small groups a sport psychologist, a sport scientist, or a member of the medical department can lead these meetings, giving players the space to air their doubts and worries. Confidential meetings can be one to one,

in pairs or in fours. The smaller the group, the more the chance that players will open up and be honest about how they’re feeling and about how they think things are going.

It’s worth noting that psychological safety isn’t simply about being nice. It’s about being forthright and candid about feelings. It’s about saying “I don’t feel great about this right now and I may need some help.” It’s about openly admitting mistakes. It’s about learning from others and finding solutions. It’s about working together. It’s about socially teaming.

By building a psychologically safe environment you’re developing a sophisticated relationship with human functioning and performance. You’re not giving in to negativity and you’re not creating a ‘can’t do’ environment. On the contrary, you’re giving your players the opportunity to become more flexible, tougher versions of themselves. You’re helping them to become more emotionally literate personally and interpersonally. You’re helping them to work together on their personal challenges off the pitch, so they can ultimately become better competitors on the pitch.

Editor's Picks

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Pressing principles

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Defensive organisation

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

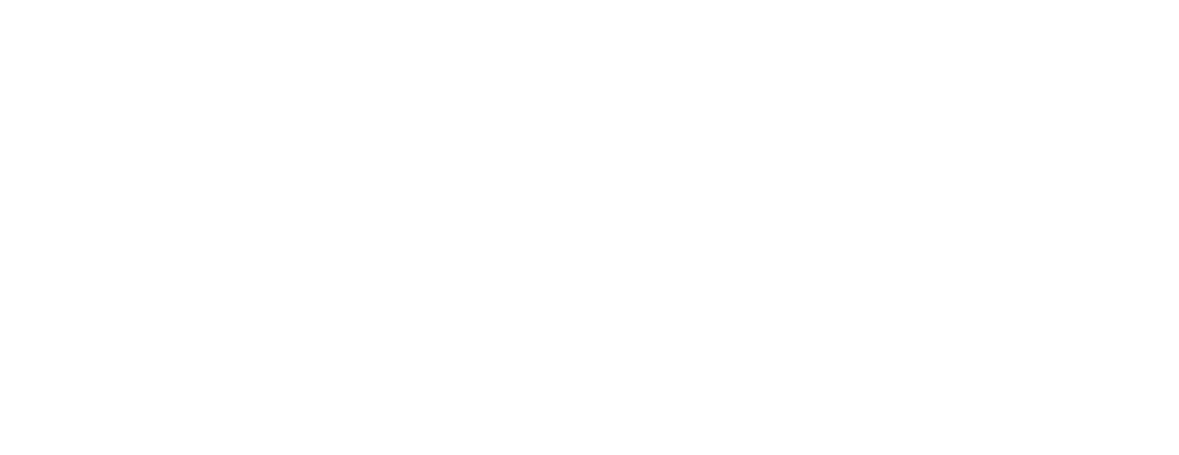

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Related

Unlocking the wing backs

Building the attack and third player runs

Play around to play through

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.