NEXT ELITE SOCCER COACHING AWARD COHORT STARTS FEBRUARY 16 - ENROL NOW

You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Lessons from the Coach’s Coach

This reviewer was lucky enough to attend a practical coaching seminar delivered by Myles Downey.

In the space of half-an-hour he turned my abysmal golf swing into something respectable, even handy. Best of all, I was no longer embarrassed by it. His trick? Simply put, Downey showed me how by removing distraction and interference, performance can be improved dramatically. I learned to stop worrying about grip, stance, power, head position and all the other million things that fuzz your brain as you are about to drive, and to just concentrate on timing the top and bottom of the arc of the swing.

Taking away the distractions led to the longest, straightest drives I have ever hit, consistently. And Downey doesn’t even play golf. This practical, workable method – the removal of interference – which can be applied to many individual sports coaching situations, is one of the key teachings from Effective Coaching. A soccer coach at the seminar returned to his training ground to improve the performance of his team’s penalty takers.

Downey’s observations about the nature of coaching challenge much of the common practice to be found on sports training grounds. Almost all, he points out, is built around the idea that coaching is essentially the transfer of knowledge. “The coach is the expert, knows the correct technique and will tell you how to perform.” We all recognise this, largely as a result of our school days and the education profession which is founded upon this approach, and to an extent it is necessary, particularly where the transfer of facts and laws of the game are required.

The Non-Directive Coaching that Downey is interested in, however, could not be more different. This does not rely on the knowledge, experience, wisdom or insight of the coach, but rather on the capacity of individuals to learn for themselves, to think for themselves and be creative. The coach is just a facilitator – someone who makes progress easier. The non-directive coach measures success by how well his players or his team learns.

To coach soccer in a non-directive way would involve stepping back from a prescriptive, drill-based, top-down approach. Instead players, though still managed, might be left much more to their own devices and allowed to find the solutions to winning themselves. The coach might set the framework and say “just play”. This might work better when the emphasis is on free flowing and creative play, rather than in relation to the technical requirements of set pieces, where direction and discipline is essential.

Downey is a follower of the coaching principles known as The Inner Game established by Timothy Gallwey in the 1970s. These set out that there is always a gap between potential and performance. People can always do better. What stops them is that ‘interference’, which is usually based on fear and doubt. So the formula to explain this is ‘Potential minus Interference equals Performance’.

Gallwey’s model therefore aims to reduce interference and increase performance. One way to reduce interference is to increase focus. When attention is focussed, a player enters a mental state in which he can learn and perform his best, something called ‘relaxed concentration.’ This is what Downey calls “flow” or what others might describe as being ‘in the groove’ or ‘in the zone’. For those who have experienced the benefits from this state of mind, the improvement in performance is extraordinary.

Downey extends Gallwey’s thinking into the concept of ‘effective coaching’, defining coaching by the outcomes. Much of this book concerns itself with the detailed mechanics of one-to-one coaching sessions and how to ensure their effectiveness, and one could see a role for the use of this in the management of professional players. The use of summarising, paraphrasing and silence to ensure understanding is one area on which Downey places emphasis in the coaching process. Asking the right questions is another.

Though much of the book is about coaching individuals, the chapter on coaching teams offers some useful ideas and tools for soccer teams, even if they are aimed at business teams primarily.

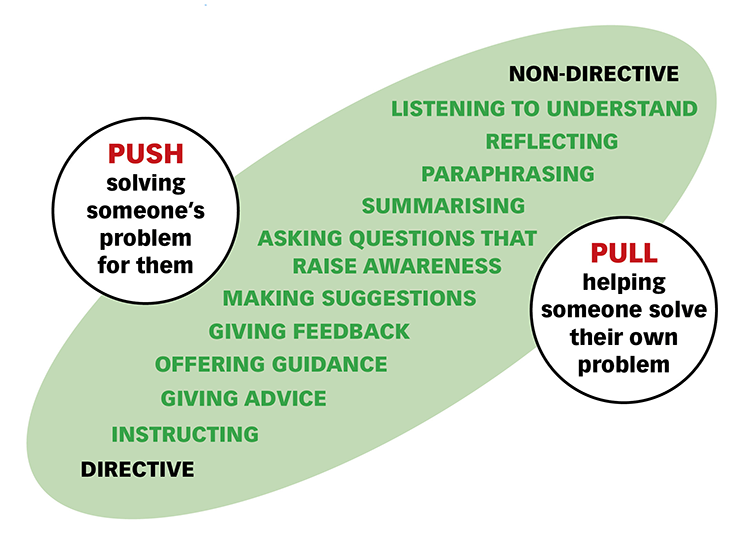

The spectrum of coaching skills

[caption id="attachment_31614" align="aligncenter" width="750"] The principle: we should spend most of our time with non-directive coaching (pull coaching) but there does remain a place for directive coaching (push coaching). The coach’s art is to balance the two.[/caption]

The principle: we should spend most of our time with non-directive coaching (pull coaching) but there does remain a place for directive coaching (push coaching). The coach’s art is to balance the two.[/caption]Individuals have a capacity for getting in their own way (by generating interference) and Downey argues that the same issue can afflict teams. One way to reduce interference in a team is to create a common vision. This is a tangible way of ensuring everyone knows they are on the same side, and flushes out disagreements about the direction the team is taking. The simplest way is to get each member of the team to write down their vision or goal and then read them out to the team, before seeking consensus.

How the goal is to be achieved is usually left to the coach, but what about empowering the players and allowing them to take more of a lead in this area? Downey also talks about achieving ‘team think’ though he also provides evidence that good teams often perform well due to such fundamental things as being together long enough to be familiar and to develop trust in each other.

Effective Coaching is a worthwhile read for those interested in the ‘how to coach’ debate.

Effective Coaching - Lessons from the Coach’s Coach, Myles Downey. Thomson Texere 223pp / Amazon.

Editor's Picks

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

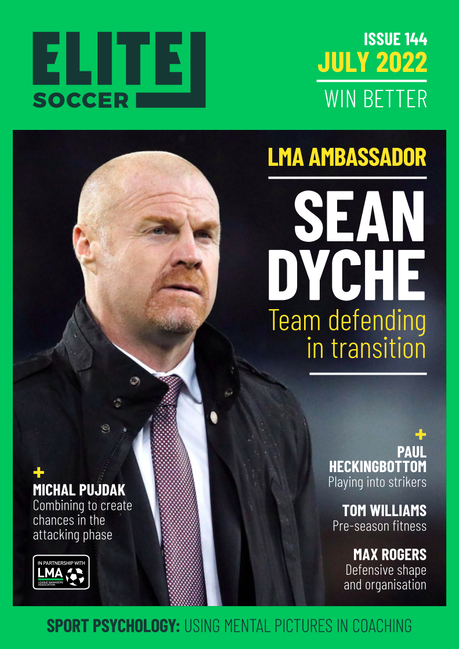

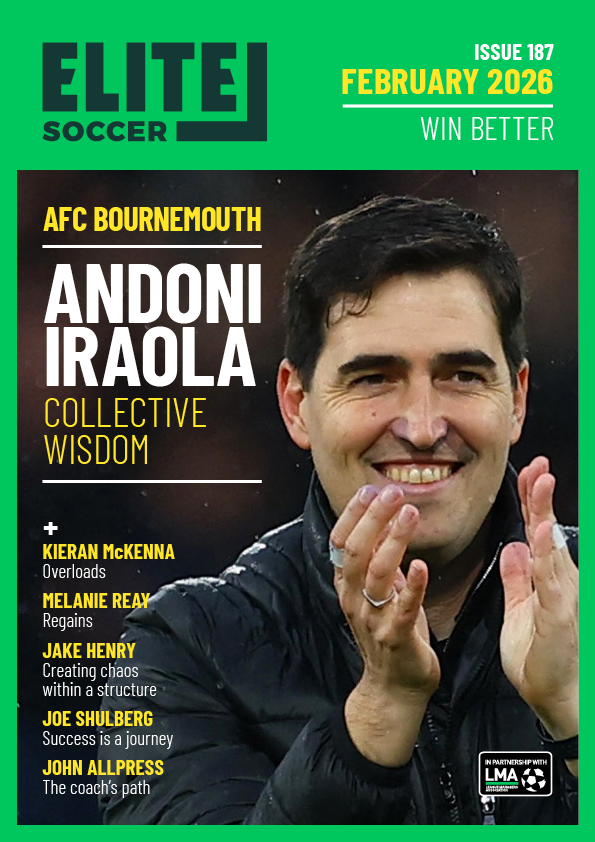

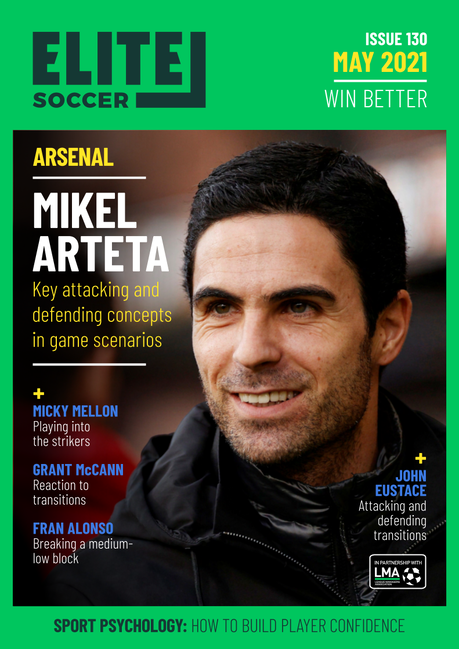

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.