OUR BEST EVER OFFER - SAVE £100/$100

JOIN THE WORLD'S LEADING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME

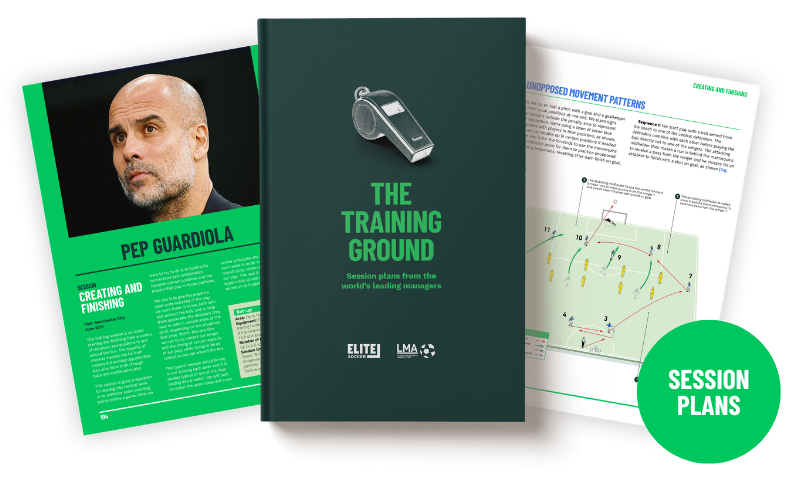

- 12 months membership of Elite Soccer

- Print copy of Elite Player & Coach Development

- Print copy of The Training Ground

You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Our man in Panama

Until recently the interim head coach of Panama’s national football team, Gary Stempel talks about the part he has played in the development Panamanian football.

Gary Stempel has played a crucial role in Panama’s football history and is credited by many with laying the foundations for the country’s 2018 World Cup qualification. But while the impact that Stempel has made on the country is impressive, his career had fairly modest beginnings.

Born to a Panamanian father and an English mother and having moved to North London as a young boy, he graduated from university and took a job as a community outreach officer at Millwall FC. Then, in 1996, following the advice of his father, an ex-baseball player and keen sports enthusiast, he decided to explore the opportunities that might exist on Panama’s fledgling football scene.

Although he had completed his coaching badges in England and was fluent in Spanish, it was a bold, some might say risky, decision. After all, he was leaving the nation with the world’s oldest professional football league to seek employment in a country where football was still only semi-professional.

However, Stempel had family in Panama and knew the culture. After a series of holidays and study visits, he decided to take the plunge.

Thankfully, it paid off. After a short spell setting up coaching schools, he broke into management and worked for just over a decade in Panama’s domestic league. Stempel made his mark quickly as a manager, winning five league titles with San Francisco and two championships with the now defunct Panamá Viejo.

But it was far from easy. On top of all the usual challenges a newly qualified manager will face in the early days of a job, Stempel found basic infrastructure and support to be sorely lacking in Panama.

“It was tough, because we were trying to coach people in what were often very difficult environments,” he says. “There were physical changes, to our training facilities and equipment, that were badly needed, but that I just wasn’t able to make. A huge investment was needed at that time in football in Panama. Just trying to get hold of some balls and cones could be a big exercise.”

Then there were the players, who were taking home $100 a month, at best, for their efforts. “Many of them had major social problems away from the pitch, and football wasn’t well paid at the time, so it wasn’t going to solve those problems,” says Stempel. “As football didn’t provide a living wage, the players would have other jobs during the day and then come to training in the late afternoon and evening.”

That, he adds, presented its own challenges, because floodlit pitches in Panama were few and far between. “There were times when we would have to use our car headlights to illuminate a small area of the pitch, just to have somewhere to train. On other occasions, the president of the club, who owned a transport business, would arrange for industrial lights – the kind normally used for fixing roads – to be brought to the club. But they’d often arrive with no petrol, so we’d have to go off and buy that before we could start training.

“Any good coach will improvise a little with training sessions, but normally how they work will be determined by the number of players and so on. For me, there was a lot to think about beyond that. There might, for example, only be certain areas of the pitch that were in a good enough condition, so we’d have to work around that.”

He recalls the training field at Panamá Viejo, which was positioned right next to the sea, making shooting practice fun and games. “Every time the ball ended up in the sea we’d have to cross the road and, if it was low tide, wade waist-deep into the mud to retrieve it.”

A HELPING HAND

Stempel also found that the support available to players was minimal, so it was common for coaches to dip into their personal finances, borrow from friends or find their own sponsorship in order to keep things going.

He found the same to be true when he moved on from club football and began to work with the Panamanian Football Federation, finding and developing young talent for the U21 and U23 teams. “The players, who were largely from the streets, were given no financial support to get to training, so often the staff and I would find the money to enable them to travel. These were the realities, not just for me, but for all the coaches in Panama at the time, and I think it did help me become a better coach. It taught me to be organised, adaptable and to think on my feet.”

It also gave him a very grounded view of what football is all about and its value at grassroots community level. “When you work in environments such as this, it really brings home the great appeal that sport can have, regardless of the circumstances,” he says. “I’ve worked here in Panama and across Central America and I’ve seen that people will improvise and work with what little they have just to set up a game of football. Even without organised teams, soccer schools and centres of excellence, communities will always find ways to play the game.”

GREEN SHOOTS

Stempel found success with his young charges, taking the U20s to the UAE for the World Cup in 2003, the first time any Panamanian side had competed on an international stage. While football was still in the shadows of Panama’s beloved baseball, the success of Los Canaleros, albeit only at youth level, meant people were starting to sit up and take notice.

Stempel, too, was building a reputation that was hard to ignore, and in 2008 he landed his dream job, leading the senior national team. He had only been at the helm for a year when he succeeded in bringing home the UNCAF Nations Cup, now known as the Copa Centroamericana, and reached the quarter-finals of the Gold Cup.

Characteristically humble, Stempel puts his incredible success that year down to “hard work and being in the right place at the right time”, but he adds that there’s a natural drive behind the Panamanian players that makes them easier to coach. “One thing you’ll always find when you’re working in these kinds of conditions, with people who have come from poverty, is that the desire to succeed is greater,” he says. “They see football as a real outlet and they’ll make major sacrifices in order to improve their conditions. Because that attitude – that desire and determination to overcome obstacles – is inbuilt in the players, it really helps you as a coach.”

FOOTBALL FEVER

Despite his achievements, industry politics meant Stempel felt unable to remain in the top job, and he returned to his former club, San Francisco, with a year out coaching Guatemala’s U17s.

When, therefore, Panama headed to Russia for their first ever World Cup, it was not Stempel, but Hernán Darío Gómez, ‘El Bolillo’, who was at the helm. Yet, it is Stempel who has been widely credited with laying the foundations that enabled them to get there. President Juan Carlos Varela, who swiftly announced a public holiday after Panama’s qualification, said of Stempel, “Profe Bolillo is closing an era, but this was built on the efforts of many men, especially Gary.”

Since he first moved to Panama over 20 years ago, Stempel has seen some major changes, both in terms of the groundswell of positive feelings towards the beautiful game and in the provision of infrastructure and support to those working in it. “Football culture simply didn’t exist when I first arrived, so it’s taken its time to catch up with other countries in the region,” he says. “Now, helped by qualification to the World Cup, more pitches and stadia are being built, there’s more sponsorship, and the players are finally earning a decent wage. Hopefully, with another good World Cup campaign, things will continue to look up over here.”

Stempel has been coaching the national U17s ahead of their World Cup in 2019, and is a FIFA coach instructor, running courses for CONCACAF across the region. Perhaps more importantly, he also recently enjoyed a second spell back in the driving seat with the national seniors, as interim manager, El Bolillo having left after the World Cup to become manager of Equador.

More than anyone, he knows what lies ahead for the Panama national team, following his recent temporary spell in charge. “We were one of the oldest teams at Russia 2018 and a number of players have since retired,” he says. “So it’s a rebuilding process. Also, I think one thing we learned from Russia is that there’s work to be done with our players in terms of learning about tactics and different systems of play.”

Editor's Picks

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Related

Pre-season fitness plan

Play around to play through

Free-kick routines

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.