ZOOM Q&A WITH KEITH ANDREWS - FEB 25 - DETAILS HERE

You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Culture and coaching

In his latest feature for Elite Soccer, John Allpress – former assistant head of academy player and coach development at Tottenham Hotspur – asks if culture transcends coaching for youth players

When working with young players, the adults involved should always ask three simple questions before they begin any interaction with them, be it a season, a warm-up, a training session, a meeting, a match or a tournament.

- Who are the players?

- What do they need?

- How can I help?

The answers to these questions are not simple and depend on many factors. The truth about working with youngsters, whether they are labelled grassroots or elite, is that it is a complicated affair that can have unforeseen consequences for all participants.

A couple of things are true, though. Firstly, one size fits no one, and if you believe it does, you are setting your players up to fail. Secondly, if you are any good, learning the subtle arts and soft skills involved in moving young minds from not knowing to knowing the paraphernalia of football, whether they be pre-pubescent or adolescent, never stops.

A cultural overview

Culture can be characterised as ‘how we do things around here’ and is backed up by our values (what we care about) and beliefs (things we hold to be true). It involves traditions and customs with established behaviour patterns passed on within a group or organisation glued together with unwritten rules, expectations and language.

The ideal culture for sporting youngsters to learn and practise should first and foremost encourage and endorse fun. If a young player is enjoying themselves, they will learn more, practise more effectively and play better. This is true no matter where you play your football. Environments should also be challenging, varied, interesting, foster a sense of belonging, and promote skilful play and the enjoyment that comes from improving and making progress.

Adults and youngsters involved in all competitive sports must quickly come to terms with the certainty that things don’t always go how they would like, and you don’t always get the rewards your performance deserves. This is where the adults must step up and lead by example, ensuring that players feel comfortable taking risks, making mistakes to learn and practise without fear of being blamed and reproached either in public or private.

Feedback should be honest and clear, constructive and useful with a focus on effort, intent and progress rather than solely on the outcome of a particular action or event.

Whilst confidence and good self-esteem are invaluable when learning and practising, uppermost in the players’ minds must be that they know their coach has their back, and that the coach would rather that they made a mistake than not try anything. Youngsters have to push the boundaries of what they know and can do because they don’t know how good they can be. Playing things safe just leaves them stuck in the quagmire of uniformity and standard practice, not moving forward in what is a fluid and dynamic long-term programme.

Adults, whether they be a coach, referee or parent, member of staff or bystander, should be positive role models and leaders demonstrating good sporting and ethical behaviour. The coach is central to this leadership role and is undoubtedly the person others expect to set the mood music for the group either in training or on matchday.

“A coach always sends a message by how they behave, and you never know who’s watching”

From timekeeping to picking the starting line-up, the head coach sets the tone. A coach always sends a message by how they behave, and you never know who’s watching. From the players the coach selects to the language they use, their behaviour is always under scrutiny and has a ripple effect throughout the group. So it is important that the coach is authentic and never promises what they can’t deliver.

The coach should show self-discipline, empathy, compassion, warmth, insight and build rapport with the players understanding their individual needs. Principally the coach is there to teach players what to expect and what is expected of them and that’s impossible without honesty and respect. This also builds a sense of camaraderie and belonging.

With young players, the coach should foster and cultivate skilful play, and a growth mindset focused on development, learning, practice and, for those who want it, mastery. Progression, not perfection, should be the objective and the watch word.

It rests with the coach to make things playful. Incorporate games and game like activities and launch learning and practice via individual, unit and group challenges so learning and practice becomes a personal experience. Follow this up with teaching. Remember the game is not the teacher, you are. The game is the players’ learning and practice tool especially when it comes to decision-making.

Related Files

There are many useful ways to help players which include challenges, constraints, conditions, direct instruction, question and answer and demonstrations and it’s the coach’s call which they think is the most appropriate for the individual’s needs at the time. These are the coach’s tools and, while they should be used wisely, they should be used when necessary.

Free play time is vital during training too as it allows for unstructured practice to encourage exploration, experimentation and creativity which has a direct carry-over into match play where interventions in real time are limited.

Skilful play is an intricate combination of producing the right technique, at the right time, regularly, under pressure in a match. In order to develop this effectively so that it does not break down when the pressure is on, the coach should offer the group opportunities for varied and open practice where decision-making is front and centre. This should be combined vigorously with technical work and brilliant basics.

Practices should be set via simple objectives to allow for maximum opportunities for players to decide when to do what. An example of this type of group challenge could be ‘Be ready to play forward’, then unit and individual challenges can emerge as play develops. This approach allows the coach to promote decision-making opportunities by adapting the rules to the players’ needs.

Using your words

The language used by the coach is also vital. For example, ‘Look for opportunities to play one- and two-touch football’ or ‘Try to let the ball run across your body and play forward as a first action’ both allow the player to make the decision because they don’t say they have to do something.

Equally, the player may need to practise and focus on a particular aspect of their play, so a constraint may be the best way to help them progress. An example of this could be ‘You cannot pass the ball backwards twice in succession.’ The coach may feel the group needs an emphasis on their passing skills so gets them to play a small-sided game with the condition focused on maximum two touch with tackles not counting as a touch.

Open questions are very powerful and help to develop players’ reflective abilities. Examples of how to construct them are outlined below:

- Touches – how many do you need?

- Spaces – what is stopping you...?

- Decisions – how will you know when to...?

- Seeing – how can you see what to do next?

- Pass – how does the pass you receive help you?

All these examples provide opportunities for players to learn and practise in games and variable practices all allowing for an element of freedom to experiment and explore options – all of which can be summed up as an illustration of ‘how we do things around here’, ‘what we care about’ and ‘what we hold to be true’.

Our subtle craft of coaching

As we know, how you coach depends on who you are coaching and what you are coaching them for. The game is simple but teaching it is not. It is complicated and, as we have seen, contingent. As a craft it is subtle and multifaceted depending on what you are coaching, the age and ability of the players, the weather, the size and mood of the group, the personality and experience of the coach and the aims of the work.

In great part it also depends on the culture of the club and the ethos of the academy. How we go about things, what we care about and believe to be true can have a profound effect on the players, their progress, learning and practice experiences as well as their opportunities to develop into fully-fledged adult professional or amateur footballers.

As a youth coach you don’t need to worry about winning; ultimately winning will take care of itself if the youth coach does everything right by the players. For this to happen, it is important that adults create a culture where players feel comfortable and confident to give things a go, because if we keep doing the right things by our youngsters on and off the pitch, in the end those with the right stuff will have a fighting chance of success.

“As we know, how you coach depends on who you are coaching and what you are coaching them for. The game is simple but teaching it is not”

Editor's Picks

Turning defence into a fast attack

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Coaches' Testimonials

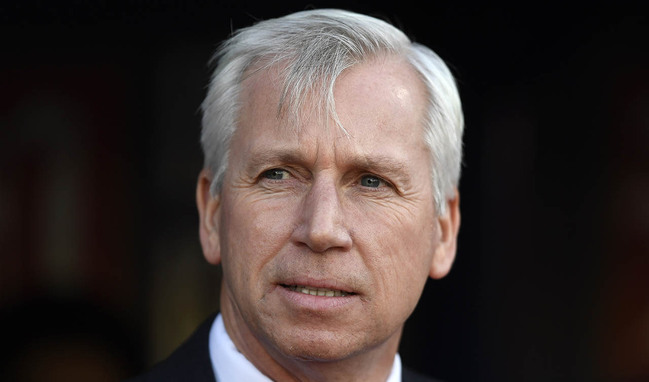

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.