OUR BEST EVER OFFER - SAVE £100/$100

JOIN THE WORLD'S LEADING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME

- 12 months membership of Elite Soccer

- Print copy of Elite Player & Coach Development

- Print copy of The Training Ground

Strategies for developing goalkeeper skills

UEFA A Licence goalkeeping coach Marco Garofalo, currently working with Torino U20s, shares his research- and experience-informed approach to developing goalkeepers

Sporting ability can be described as the set of physical, motor, and mental competencies that allow an athlete to perform a sporting activity effectively, from coordination to the ability to learn new skills, which are developed through training and experience. It’s the result of a combination of genetic predispositions and abilities that can be improved and refined with practice. That means the coach should develop personalised strategies to improve and maintain these abilities, adapting the training to the needs and context in which they operate, and creating a session that’s versatile and customisable to optimise results and maximise the individual performance of goalkeepers.

Scientific research and practice

Skills develop primarily through their practice, which includes targeted repetitions of specific tasks and error correction. These exercises increase individual participation by encouraging task repetition and interaction with the ball, promoting their development and retention over time. Activities must be conducted by the coach, and the exercises should be both mentally and physically challenging with the aim of perfecting specific skills, adapting the difficulty to the talent of the goalkeepers.

In football, high-level players and coaches have customised training to improve specific skills. Andrea Pirlo and Gianfranco Zola, for example, perfected free kicks inspired by Roberto Baggio and Diego Maradona, while Fabio Capello and Marcello Lippi worked individually with Zlatan Ibrahimovic and Gianluca Zambrotta to refine techniques such as shooting and crossing with the weaker foot, confirming the importance of targeted training for the development of specific skills.

Specific goalkeeper training

The role of the goalkeeper requires specific technical and tactical skills that set them apart from other players and so they also need targeted training. Within the team, their involvement varies depending on the exercises, which are often adapted to develop the abilities of their team-mates or to meet the coach’s specific tactical needs.

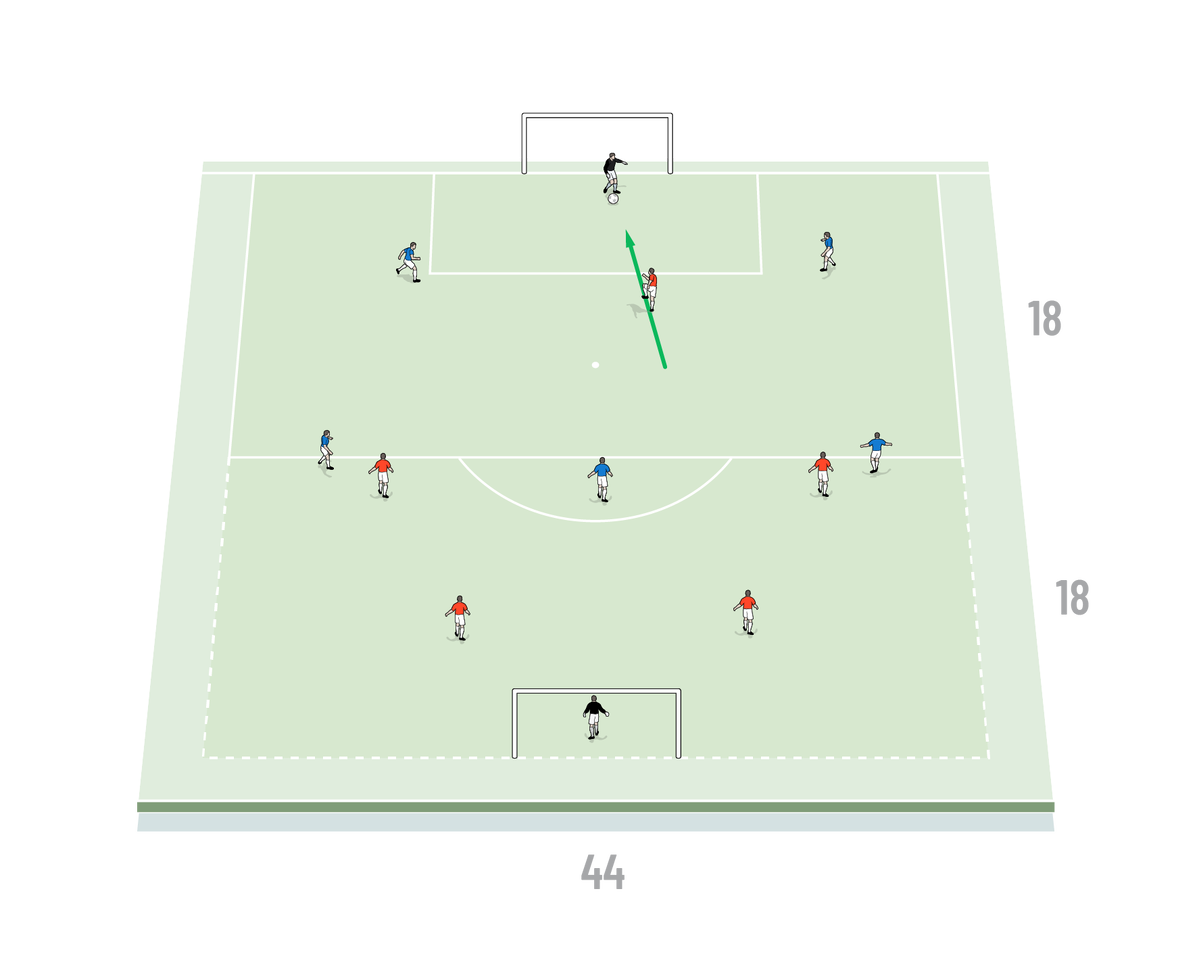

For example, in a 5v5 exercise with two goalkeepers (Figure 1), there are numerous opportunities to make decisions thanks to the frequent interaction between players and the ball. However, a goalkeeper at the beginning of their specialisation might struggle to handle the ball under pressure due to limited space and reduced time, as their control and passing skills are not yet well developed. Similarly, a goalkeeper skilled only with their right foot might make decisions based on already acquired competencies, limiting themselves to using their strong foot. In fact, in this type of exercise, it is more likely that attention is directed towards decision-making, results, physical aspects, or enjoyment, rather than the acquisition of new technical skills.

[Figure 1]

Learning

Based on the objectives (technical, tactical, or coordinative), the coach designs exercises, acting as a ‘facilitator of learning,’ and plans the session so that it progressively approaches match conditions. This involves adjusting the level of challenge without overloading the number one but allowing them to work at the limit of their capabilities.

For those reasons, the training methodology involves a progression in three phases. In the technical realm, it starts by working on mechanical precision (analytical phase), then integrating skills into coordinated patterns (applied technique). Finally, it moves on to practising tactical aspects through situational training, where skills are tested in contexts similar to a match. Then there’s the importance of training coordinative abilities and the goalkeeper’s involvement with the team, which is fundamental for learning to play with team-mates.

By practising applied technique and situational training, the goalkeeper has the opportunity to reflect on their own actions and errors, meaning they can then begin to model the behaviour they want and transfer their technical and decision-making skills from specific training to team play.

Analytical training

Analytical training can be useful in the initial phases of the specialisation process, for the coach’s needs or to optimise the workload. In these cases, the goal is to manage the goalkeeper’s energy so that they can maintain a high level of performance without excessive fatigue, both in preparation for the next match and to prepare them for more intense exercises within the same training session.

Beyond the physical aspects, it allows focusing on the mechanical details of the movement, such as the orientation and alignment of different body parts, the timing sequence of gestures, and their trajectory. In this way, those who are not yet familiar with the dynamics of movements can progressively gain mastery.

For example, to teach the chest catch technique, you start by throwing the ball always to the same point, maintaining a constant trajectory and speed. The exercise is repeated many times until the goalkeeper becomes familiar with the movement.

Learning technical gestures through the analytical method is undoubtedly important, but it should be balanced with exercises that encourage the ability to adapt to the motor challenges arising from the game environment, which characterise sports classified as “open skills.”

Applied technique

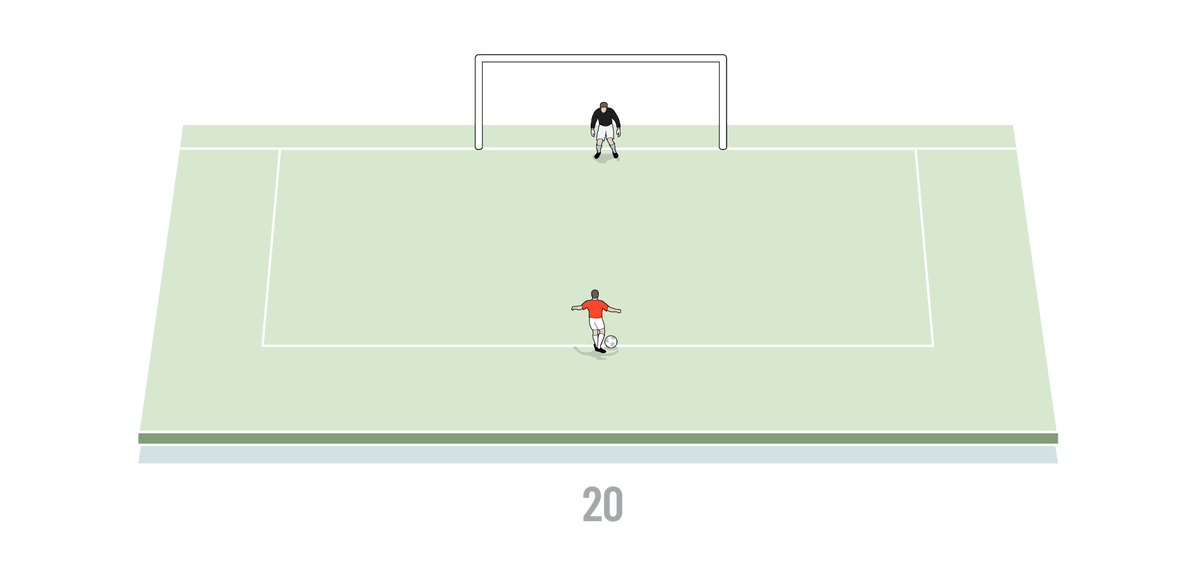

To tailor technical gestures to the variables of the game, perceptual and cognitive skills should be trained to recognise them. These abilities enable the goalkeeper to quickly interpret changes and use coordinative capacities to adapt basic techniques into movement patterns coordinated with the game’s dynamics, such as the behaviour of the ball and the actions of opponents or teammates. This involves fluidly engaging different parts of the body to gain a performance advantage. Young players and amateurs tend to execute jerky and hurried movements due to a lack of familiarity with these patterns. In contrast, more skilled goalkeepers perform them with fluidity and naturalness, demonstrating a greater ability to simplify complex tasks and handle difficult situations more efficiently (Figure 2).

[Figure 2]

For example, in game activities where the technical gesture of the collapse dive (or leg removal dive technique) is required, the simplest variation to interpret can be the behaviour of the ball. Therefore, in the exercise, varying the intensity, angle, speed, and trajectory of the shots pushes the goalkeeper to constantly adapt the basic technique by making small adjustments, such as positioning the leg forward or backward to precisely intercept balls of different speeds.

This method is often confused with the analytical one, but the main objective is to promote the adaptability of movement, which is fundamental in a match, rather than perfecting the mechanics of the gesture.

Tactical skills – situational training

The goalkeeper’s individual tactics encompass the actions and decisions made to achieve specific objectives within a team strategy. This requires the ability to assess the context in real time, identify opportunities or threats, and adapt one’s behaviour to optimise performance. For goalkeepers, these tactics include movements, positioning, timing choices, consideration of other players, and the execution of specific techniques, all aimed at gaining a tactical advantage and contributing to the team’s success.

Just as with technical skills, individual tactical skills develop through theory, practice, and feedback. Consequently, it is important to perform specific exercises in predefined scenarios to provide the opportunity to quickly analyse the context and make effective decisions. In team drills, opportunities to make crucial decisions might be limited—for example, in exercises where attackers intercept crosses, the goalkeeper rarely has to decide whether to come out or stay in goal.

So it’s possible to design activities in the form of situational exercises to stimulate the goalkeeper’s ability to choose the right moment to act, but in a more specific context. To this end, exercises with crosses are performed, varying the difficulty through the shooting distance, the introduction of mannequins, and an assistant to simulate the presence of other players (Figure 3).

[Figure 3]

Note that the mannequins are inflatable and the assistant coach simulates volleys and headers using a shield designed to alter ball trajectories

This configuration recreates a scenario where the ball has a speed similar to that in a match, training the goalkeeper to make choices based on the trajectory of the ball and the movement of the assistant, with timing closer to that of real play.

Simultaneously, it refines the technical skills already acquired and improves the ability to predict the ball’s trajectory.

Through repetition, in addition to obtaining the mentioned benefits, the goalkeeper has the opportunity to reflect on their own responsibility in case of errors, promoting the emergence of desired behaviours.

Related Files

Editor's Picks

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

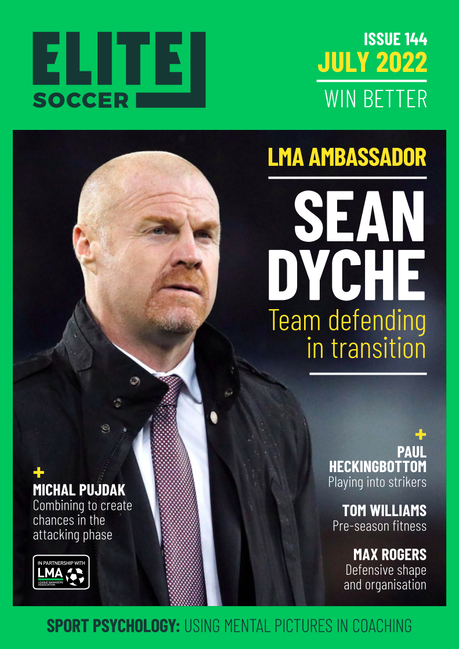

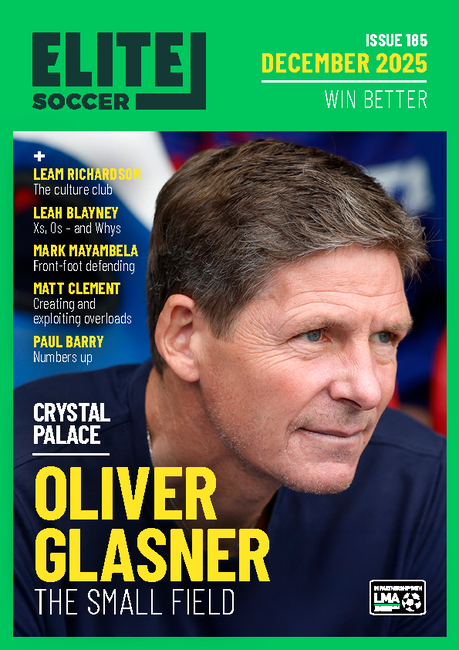

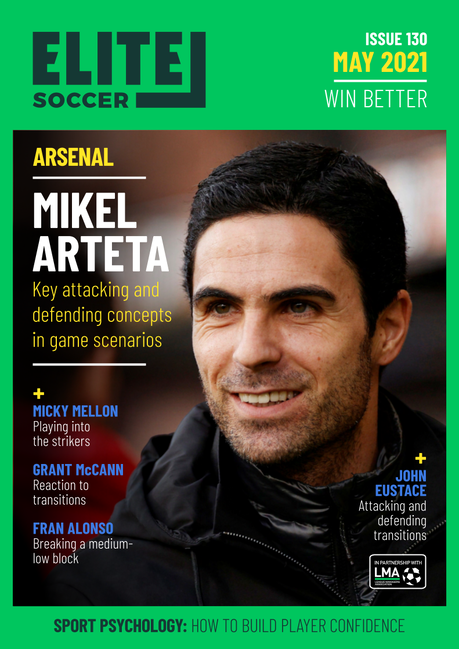

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.