ZOOM Q&A WITH KEITH ANDREWS - FEB 25 - DETAILS HERE

You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The coach’s path

John Allpress reflects on his life in football and the importance of continuing to develop as a coach.

No matter who you coach and at whatever level of the game, if you are any good, learning the subtle art of moving players from not knowing to knowing stuff and the soft skills that bind that process together never stops.

I had passed my FA Full Badge course in 1977 (later converting it to the UEFA A Licence), which was certainly too young as I had very little experience at 25 of either teaching (I was a teacher by profession then) or coaching in general. The courses in those days were held over a fortnight at Lilleshall. Candidates played and coached every day - except the middle Sunday – for two weeks. It was tough on the body and the mind, like pre-season with brains.

My group coach was Colin Murphy, with the course culminating in final coaching sessions of 30 minutes. My topic was ‘coach players to create and exploit space in midfield’ in front of the director of coaching Charles Hughes: no pressure then. Two out of thirty in my group passed. We didn’t find out straightaway in those days, but a couple of weeks later a letter arrived from Lancaster Gate confirming my status had changed.

I was still playing and coaching the school and district teams, with the boys doing quite well, winning the occasional cup competition. During this time, I dabbled with the professional youth game, working with the schoolboys at Charlton Athletic and Tottenham Hotspur with their under-15 squads training on a Tuesday and a Thursday evening; this was part-time and very similar to my district team’s level.

I left teaching and worked full time for the FA as a football development officer and then, after returning to teaching part-time, as an FA monitor, visiting and supporting coaches at various centres of excellence. During this time, I staffed FA courses including the FA Teachers and Leaders Awards, the FA Preliminary Award, the newly devised UEFA B Licence and UEFA A Licence preparatory courses. All these experiences helped me hone my coach educator skill set and they were very valuable, but they were nothing compared to what was to come.

The Old Aloysians AFA Cup Winning team 1976. John is front left

A steep learning curve

In 1997, when the FA football academy programme replaced the centres of excellence, I joined the fledgling Ipswich Town academy. The club already had a well-respected youth development programme, but the academy took this to a whole new level with schoolboy players ranging from eight to 16 years old and scholars and young professionals from 17 to 21.

My learning curve at Ipswich was steep, but luckily for me I was surrounded by good people like Bryan Klug and Paul Goddard, in a stable environment which helped me learn the ropes. I had never been full-time at a professional club before and found that I had a lot to learn. Less than 2% of academy players end up with a job as a full-time player and I had to adjust to life in that world and do it quickly if I wanted to survive and then flourish.

Ipswich were known as a passing club. My first discovery was that on a day-to-day basis my library of practices was well short of what was required and the standard of what I was prepared to accept was not good enough. I was yet to learn what good looked like at those levels.

I set about watching and finding out what I needed to know from the experienced staff that worked there and asked a lot of questions. The biggest lesson was to always teach to the top rather than community coach or teach like I was still a PE teacher. The best players always had to be challenged, and the peloton had to keep up. The boys were told that if they made a mistake to try to get back into credit with the next thing they did.

Out of the comfort zone

In 2000, with Ipswich promoted into the Premier League and the academy now established, I rejoined the FA, firstly as a regional director and then as the national coach for young player development working alongside the late great Craig Simmons. Together we developed the FA Youth Coaches Courses for staff working in the academies with young players in the under-11 and 12 to 16 age ranges. These courses later evolved into the FA Youth and Advanced Youth Awards.

I was also involved with the national youth teams at under-16 and under-17 level. If my learning curve at Ipswich had been steep, it now became even steeper. Now I was staffing national courses, regularly visiting academies based at professional football clubs, scouting for the national youth under-16 team, and travelling with national teams on international duty. I was definitely out of my comfort zone, but again I was lucky to be surrounded by very good people and top practitioners like Les Reed, Dick Bate and John McDermott as well as my mentor Craig Simmons.

Travelling with England and staffing national courses was nothing like anything I had experienced before. It was 24/7 and tested me, a natural introvert (which I know will surprise some people), to the core, physically, mentally and emotionally. But every trip and event was an opportunity to learn, and, once they were over, there could be a period of self-reflection and a chance to work out if I had improved as a coach and a person.

Related Files

Coaching is not supposed to be simple

What I quickly worked out was that working at this level wasn’t supposed to be a walk in the park. Every job was different because the personnel involved (players, staff or course candidates) were different, and that while nailing this national coach job wouldn’t be easy, there were routines and habits that could be adopted that would help me grow into it. I had to be both humble and confident: humble, because I had a lot to learn, and confident that I could rise to the challenges the environment presented.

The first thing that became apparent was that details matter. At that level, you can’t just wing it. The minutiae have to be nailed down. Just knowing your job isn’t enough. You have to do it regularly, on demand, under pressure and then 50% more because you’re in a team and it’s teamwork that gets you through the tough bits.

You also have to plan for every contingency. Things go wrong in football a lot, so you have to plan for failure and the what ifs. The work we did with the players was simple stuff, but it had to be done to the highest standards. Meetings had to start on time and be short and sweet so as not to overload everyone. When planning for a matchday we worked it back from the kick-off before going on to nail down things until the boys were back at their hotel.

All the staff knew their jobs and various scenarios were planned for. We knew where the nearest hospital was if a player was badly injured and which staff member went to the hospital (usually the doctor). If a second player needed to go to the hospital, who went then? Who managed a sent-off player? The devil was in the detail so that whatever occurred everyone knew their job and there was no panic. A calm bench is an efficient bench.

My job was the set plays as well as helping the head coach with the technical preparation. I led the set play workshop during the week and did the practical run through on matchday, compiled the set play book for the bench and briefed the subs going on. Because of the way we did it, the players not only knew their job but everybody else’s too. I knew the job off by heart and can remember the England set plays we used at the time to this day. On matchday I also took the warm-up with the sport scientist.

Because these trips and events were so full on, it was important to grab some rest time when it was available. The mantra was when there’s nothing to do, do nothing. Go to your room and put your feet up, even if it was just for half an hour. Grabbing some time to myself was very important as I found it put me in the right frame of mind for the next job.

A stratospheric challenge

Working with the FA was a great job and it gave me the opportunity to meet some terrific people both inside and outside the industry. This set me up beautifully for my next challenge. In 2013 I left and joined the Tottenham Hotspur Academy, staying there nearly a decade until 2022.

If my learning curves at Ipswich and the FA had been steep, at Tottenham they were stratospheric, a real challenge, and once again I found myself in a stable environment stacked with dedicated and talented people ambitious to improve and have a career in football.

Regularly producing footballers good enough to get a career playing professionally in the hardest league in the world which is full of elite players from around the globe is a tough assignment. At the time, the Tottenham academy, under the leadership of John McDermott, was achieving just that. At Spurs, like the FA, brilliant basics had to be performed to an elite level by both staff and players for them to have a fighting chance of staying the course. The standards were high, but everyone was expected to get even better.

Youngsters were expected to play with courage, to have a go at new things, to get out of their comfort zone and the staff would rather they made a mistake than didn’t try anything. This message didn’t just come from John McDermott but from the manager himself. Both were on the same page which was a tremendous help.

Standards were set high for the staff too; standing still wasn’t an option for them either. If we wanted to produce elite footballers, the staff had to model the elite behaviour required to lead the players, and like the players they had to be on a path of constant improvement as well.

This level of challenge wasn’t for everyone, and some people (both staff and players) fell short. Others survived and thrived, moving forward significantly in their careers to senior jobs in the game both internationally and at club level. The philosophy was players first and I loved it.

Supporting coach development

Part of my role at Tottenham was to support the development of our academy coaches: helping them to enhance and add to the skills they needed to keep our players on track during what is a very long audition. To this point, as you would expect, the coaches’ journeys had all been different. Some had been full-time professional players with varying degrees of success, others, like me, were part-time professionals alongside a teaching career and some had worked their way up from the club’s community programme. Some had been coaching a long time, others not very long at all. The task was to get them all to buy in to the way we did things and become custodians of our culture. To do this effectively they had to know what to expect if they worked with us trying to produce elite players for Tottenham and what was expected of them in the way they worked and behaved.

It was crucial for staff to keep in sharp focus why they were there. First and foremost, their job was to help the players get better and stay on a path of constant improvement as footballers and as people. An academy coach has to learn not to treat small hiccups, like losing a football match, as a disaster, as all sorts of little variables have the potential to throw a spanner in the works of players’ development pathways.

My aim was to train our coaches to keep focused on the long-term objective, even on a matchday, where coaching has the potential to become reactive. The questions were always the same. Did we have the best players on the pitch? Did we have the courage to try the things out we had been learning and practising? Did we find out something new about the players? Did we have any leaders when things went wrong?

To help me set about this part of my job I divided my approach into four different areas depending on who the coach was, what we agreed was needed for individual progress to be made and how I thought I could best help them.

These four categories were:

1 – Personal: How could I help an individual add to what they already knew and could do and support their improvement to regularly produce work to the standards required to help our players get better and flourish within the academy culture?

2 – Mandatory: How could I help and support individual coaches gain the qualifications they needed to work at the academy and advance their careers in the game?

3 – Inspirational: How could I best support our most talented and senior staff and expose them to elite practice and environments, both inside and outside the football industry, so that they could fulfil their potential and flourish within the game either at Tottenham or elsewhere?

4 – Continued Professional Development events: These focused on particular development needs and general topics for the whole staff, which included weekend workshops after training and shorter lunchtime seminars.

The truth about coaching is that it is for the most part a chancy affair, often complex and random in nature. It is subtle and multifaceted, depending on what you are working on with the players, the age and proficiency of those taking part, the size and mood of the group, the weather, the culture of the club, the personality and beliefs of the coach and the aims of the teaching. How you coach depends on who you are coaching and what you are coaching them for.

Attitude, though, is a decision. The academy coach, like their players, can decide how they are going to turn up. The players need the coach to be on it from the word go. Outside factors sometimes play a part but throughout the season the coach should remind themselves of their overarching objective, to help the players get better and the academy philosophy, in Tottenham’s case – players first.

Simplicity like this helps clarity and stops people getting bogged down in the minutiae of the job like winning and losing, unnecessary focus on tactics or poor refereeing decisions. If you feel yourself getting bogged down, take a beat, remember where you are and why you are there; don’t jump in and say or do something you’ll regret. You never know who’s watching, but you can be sure that the players and their parents are.

It’s important to build good habits and routines, like good time keeping and players being responsible for looking after their kit and equipment, as well as keeping dressing rooms clean and tidy, and leaving rooms as you find them. Things like this go a long way to building character and discipline in a squad. Never leave undone any little jobs that need to be done, even when nobody is watching or even when it’s not your direct responsibility.

During my development journey I have tried to deal with the people I’ve met honestly, aimed to be myself and not promised what I couldn’t deliver. I have met some really top people and some excellent coaches and coach educators and made some really good friends. I hope you do the same and enjoy the challenges as much as I did during your own development as a football coach and teacher of the game.

Editor's Picks

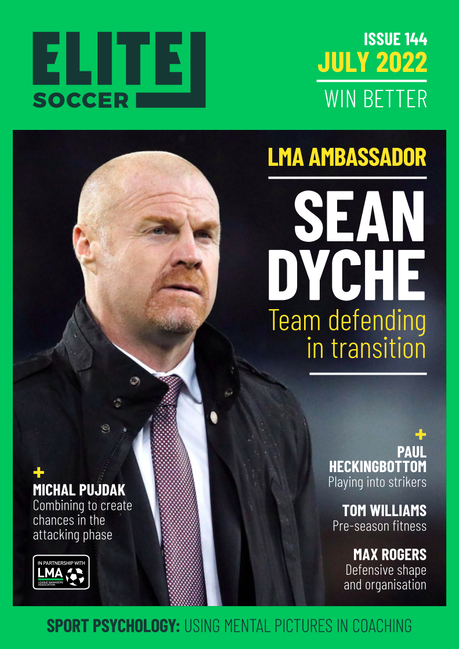

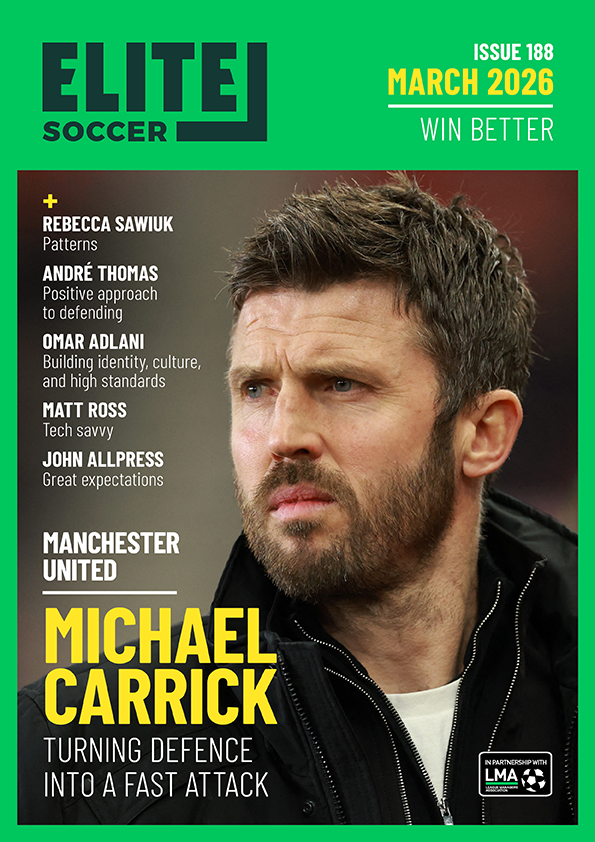

Turning defence into a fast attack

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

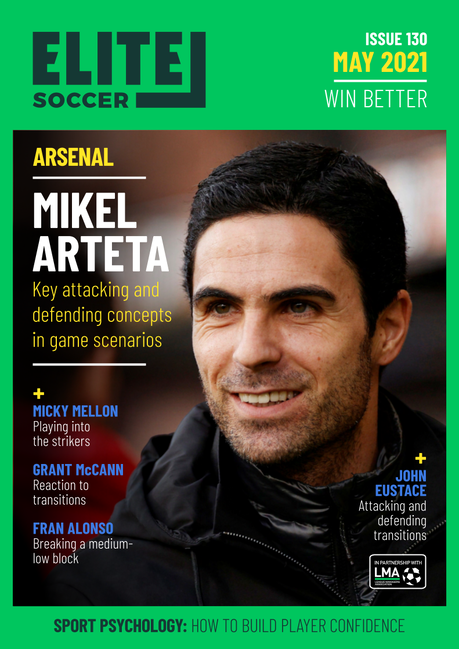

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.