OUR BEST EVER OFFER - SAVE £100/$100

JOIN THE WORLD'S LEADING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME

- 12 months membership of Elite Soccer

- Print copy of Elite Player & Coach Development

- Print copy of The Training Ground

You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The power of coaching

Arsenal’s academy coach developer Matthew Joseph spoke to Ben Bartlett in a recent webinar for the Elite Soccer Coaching Award

Matthew Joseph likes to list key ideas in threes – and he has a trio of behaviours that coaches do regularly.

“We teach, we coach, we manage,” the Arsenal academy coach developer says. “We teach people things that they don’t know have limited understanding of, we coach players how to use their attributes and their capabilities, and we manage behaviour.”

Matthew himself was a promising youngster, spending time at the National Football School at Lilleshall where they focused heavily on player development, before being released from Arsenal without making the breakthrough into the first team. Looking back on that experience, he wonders if he lacked self-belief, and that idea now shapes how he works with coaches and players.

“What do they believe about themselves? What do they believe to be true? What do they believe that they can instill in others?

“When I was a young pro and we were asked to go over and support the first team and [first-team manager] George Graham, I was so fearful of going there and making a mistake. Some of the other players, someone like Ray Parlour, he had no care about going over and playing. He was able to take the opportunity because he believed that he was good enough to be in that arena.

“You can be very good, but sometimes there are people who are better or more trusted than you. It might not be your time at that moment.”

Building trust

That has played a major part in his work now as academy coach developer – going full circle back to Arsenal, where he wants coaches and players to be aligned in their work and objectives.

“How do players build trust for you as a coach? Do we know what those things are? What are the things that we look for when we are working with young players for them to be able to build trust? Then we want to make sure the players have an understanding of what that might look like, but also speak to players and find out what they believe to be true of how they build trust, how they build a career, because it’s really easy to say, ‘I think I’m better than someone else,’ or ‘Someone else is better than me’.”

He adds: “As much as it’s difficult and it hurts, sometimes you’re not ready for an environment, but you just don’t know you’re not ready. Someone else who has more experience realises you’re not ready for that yet, and so you have to come out of an environment, and you have to leave it until you are ready.”

Matthew carved out a career in the English Football League, most notably at Cambridge United and Leyton Orient. He reflects that it took resilience for him to be able to do that.

“From the point of being released to the point of getting a professional contract was 20 months and 21 trials at different clubs,” he says.

It’s no wonder that he has such a breadth of knowledge of coaching styles and structures. He spent the best part of a decade and a half at the FA, firstly as a skills coach. He describes his grassroots work as “a real big privilege”.

“Something which I’d always recommend people to do is to go and work in the grassroots game and work with young people who have got loads of intent and loads of enthusiasm,” he says.

As much as it’s difficult and it hurts, sometimes you’re not ready for an environment, but you just don’t know you’re not ready

What it takes to win

Moving on to work as a regional coach, he worked in the boys’ game as well as the women’s and girls’ game, supporting clubs across London, and then became an FA coach developer.

“I learned a lot about how people learn, sometimes how boys and girls learn differently, and the power and the art of communication,” he says.

His own experiences mean that he encourages coaches to measure success in different ways; ‘winning’ does not necessarily mean winning matches. He points to the Arsenal academy, where he sees education as the first priority, followed by the behaviours the coaches want the players to exhibit.

“Whether we win the game or not, what are the behaviours that we want the players to exhibit and understand and be able to understand and recognise and apply? Those behaviours need to be built and refined, used in every moment of the game when they become adults. At a younger age, your players may not have the cognitive processes to deal with winning. They might not have the physical capabilities. They might not have the technical execution.

“But actually, I can have the winning behaviours even if I can’t put all the pieces of jigsaw together yet.”

He uses a concept that British Gymnastics have used: “What it takes to win”. For coaches, Matthew suggests, this means breaking down behaviour into two areas: accountability and responsibility.

“I’m accountable for my actions and my behaviours, but can I be responsible for the behaviours and the actions of other people?

“Bear in mind, it’s a team game, I can’t win the game on my own. But what I can do is work with other people, making sure we have a clear objective, and we can demonstrate the required behaviours to go and win the game.”

Related Files

Identifying winning behaviours

Once a team begins to win matches, opponents are more and more driven to stop them, and Matthew says that coaches then need to consider what players need to do to continue their run.

“Can we influence, dominate, manage, take the moment? Then if we’re clear on that, then how can we help those moments to become a collection of moments? That collection of moments will turn into momentum, so how can we keep momentum?

“On the flip side, how do we break it? Winning might be that we’re really good at breaking momentum. Football goes through different stages, and there was a stage where everyone wanted the holding midfield player who could break the game up.

“Your winning behaviours will depend on what you want. Somebody in your team is going to have to stop the ball from going in the goal, somebody’s going to have to find ways of creating chances to score, and someone’s got to put it in the back of the net.

“In the modern game, at the highest level, players can do all three things, but they might have a preference or priority for one, but they’ve got an ability to do all three. If you have eleven players in your group that can stop goals, create goals, and score goals, you’ve probably got more chance of winning!”

Coaching towards that win should also be differentiated according to the qualities of the individual players a coach is working with. Matthew gives himself as an example: a full back who was relatively small, standing five foot six.

“The chances are people are going to send it forwards. If they’re bigger, they’re going to try and pull on to me. What are my coping strategies? How do I preempt that? How do I make sure that doesn’t happen, and if it does happen, how do I make the best use of it?”

He compares the different attributes of England full backs Kieran Trippier, Kyle Walker, Trent Alexander-Arnold and Reece James.

“What does that mean for the person that plays alongside them as the right-sided centre half?

It means your role is slightly different with all of them. You probably don’t need to cover Kyle Walker as much because he’s got blistering pace, but you might need to cover Kieran Trippier; although he’s quick enough, you might have to help him or be more concerned about crosses going into the back post.

“You can’t just look at what you’re going to do and deal with the person you’re marking, although that’s your priority, and you’re accountable for your role.”

And that applies to coaches just as much: “What’s your responsibility to those on the pitch and those on the side of the pitch? You’re trying to help all of them achieve a goal.”

On the journey

For youth and academy coaches, it’s important to remember that players’ attributes may change; he recommends evaluating them on consistency, effectiveness and efficiency.

“We’re always trying to look at what we think the players could be, so we’re looking at their potential in two years, four years, six years, but we can’t forget about them now,” he says.

And coaches too are on their own individual journeys regardless of their specialisms and ambitions: “Sometimes you don’t realise the things that you’ve been through and the things that have shaped you,” he says.

And he invokes a quote that might surprise some, but that he thinks is very pertinent to any football coach.

“I remember watching [the film] Nanny McPhee with my kids, and she says to the parents, ‘When the kids need me but don’t want me, I’m staying. When they want me but don’t need me, I’m going.’ That’s the point of being a coach. When they need us, you have to show up, and you have to be there. When they need you, do they need you to teach? Do they need you to coach? Do they need you to manage?

“But then they need to be self-directed and do things on their own. I’ll always be there when they need me, but I’m not going to be there just because they want me to be there.

“You need to be ready, you need to be prepared every time, and within that, you need to be consistent.

“You have to be the best version that you can be as a coach to help the players. That’s non-negotiable.”

Editor's Picks

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

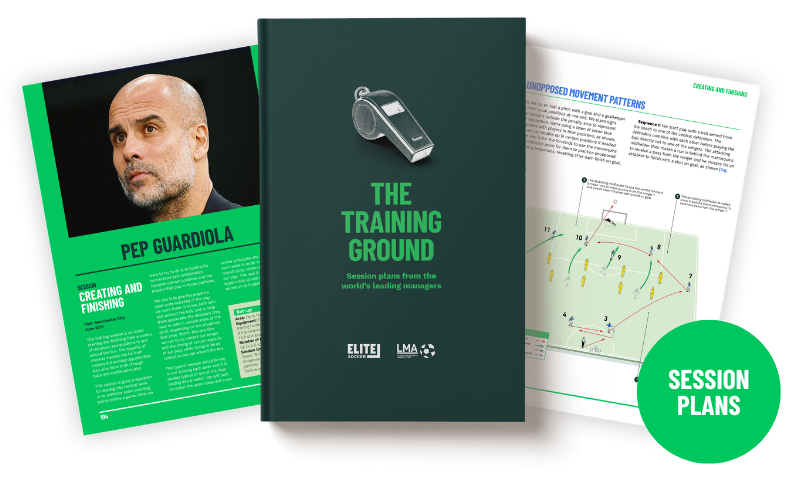

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.