OUR BEST EVER OFFER - SAVE £100/$100

JOIN THE WORLD'S LEADING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME

- 12 months membership of Elite Soccer

- Print copy of Elite Player & Coach Development

- Print copy of The Training Ground

Relationism in theory and practice

Jamie Hamilton explains how he came to define relationism, and how he coaches it with his under-16s academy team

Interview: Ben Bartlett Words: Steph Fairbairn

Jamie Hamilton took up coaching in 2013, a year after Pep Guardiola left Barcelona.

The four years Guardiola spent leading La Masia are lauded by coaches, players, fans and critics alike as a seminal time in soccer. In the modern era, there is arguably no other team that has had the cultural and tactical impact of Guardiola’s Barcelona.

Hamilton certainly believes so. “One of the main references and inspirations for me when I got into coaching, having been a football fan all my life, was Guardiola’s Barcelona,” he said.

“The impact of Guardiola’s Barcelona cannot be overstated. That team was absolutely incredible. It caught the imagination of the world, really.”

The team was known for what the globe calls ‘tiki-taka’ or ‘juego de posición’ (positional play).

Whether or not Guardiola aligns with the names placed on his style of play by others – Guardiola famously told Catalan journalist Martí Perarnau, “I loathe all that passing for the sake of it … Barça didn’t do tiki-taka! … You have to pass the ball with a clear intention, with the aim of making it into the opposition’s goal” – the concepts captivated coaches.

Hamilton was one of them.

“I spent some years coaching grassroots, local clubs, then moving into more independent academies, in various situations and environments, but I would always primarily be looking to implement and study and learn about positional play,” he said.

“I went quite deep with it, like a lot of people. I began to work out ways of practising it, with positive results. And that’s one of the reasons why positional play is so popular; it works, you can get good situations on the pitch.”

But for Hamilton, there was always what he calls a ‘nagging tension’, due to his interest in other schools of thought, such as ecological dynamics and constraints-based coaching.

“I was always interested in those kinds of discussions,” he explains. “And that, of course, has a lot to do with opening the field of affordances and not being too instructive or prescriptive. And one of the things I found when I was coaching positional players was that I had to be prescriptive.

“That’s not to say that there are coaches that can’t do it. Of course, they can do it way better than I could, but I had to tell players quite clearly what to do in a lot of situations. There was always a tension there but, to be honest, I just thought ‘if you want to play possession football, controlling football, this is just what you have to do, this is just the way it is’.”

Hamilton’s interest in new developments in the game and continued learning then led him to Italian manager Roberto De Zerbi (currently with Marseille in Ligue 1), also famed for a positional style of play. It was the close proximity of the players on his teams that caught Hamilton’s interest in particular, something which he says “is not typical of a lot of positional play, where teams usually spread the players out on the pitch”.

“I’d also always liked Red Bull football,” he shares. “I’d always liked this kind of proximity aspect. I was always interested in transitions. I’d always liked it when the players were close together.”

De Zerbi, Hamilton says, almost acted as a ‘gateway’ to his next find, his moment of clarity: Fernando Diniz’s Fluminese.

“That was the moment for me,” he says. “It fried my brain, to be honest, because I was watching football that clearly worked.

“The team was punching above its weight at that point [in 2019]. They were top three in Brasileiro [Campeonato Brasileiro Série A, the highest level of the Brazilian football league system] with a brown budget that should have seen them eighth or, ninth in the league.

“They were overachieving and playing football that I didn’t understand. They kept the ball, they dominated possession, but they were not doing positional play. And not only were they not doing it, they were doing something quite radically different.

“To me, it looked like complete off-the-cuff intuition and spontaneity of the players.”

Hamilton’s interest in the way Fluminense were playing led him to connect with others also interested in the style and delve deeper, watching, he says “every minute of that Fluminense team, analysing everything so closely”.

In doing so, he found common patterns and motifs in the play, and began cataloguing and collecting them, while continuing to speak to and learn from others invested in the style.

The next step was to begin to define some aspects of the style with the goal, Hamilton says, of “crystallising my understanding to get something I could grab hold of because the implementation was so mysterious to me”.

This process of ongoing research, learning and experimentation then led him to what he termed ‘relationism’.

What is relationism?

Hamilton first introduced the term in November 2022. He calls it ‘a paradigm of football,’ a translated twist on the term ‘jogo functional’, a style which has characterised Brazilian football since the 1940s, but which was first named as such by writer and football analyst Jozsef ‘Hungaro’ Bozsik in 2018.

As he details in a 2023 Medium post, relationism is ‘a lens through which the game can be theorised, practised and developed’.

Rather than using abstracted flattened space as a primary reference for player organisation, as in positional play, relationist players move together while communicating through signals and cues often undetectable by those schooled in various other strains of football thinking.

Hamilton says: “If we talk about it in terms of reference points, what are the reference points that are popping up in the player’s perceptual field that can be useful for a coach to amplify if you want to try and achieve some coherent, effective, functional relationist attack?”

In the Medium article, he goes on to list seven (by no means an extensive list) ‘tactical patterns and motifs commonly found in relationist play’, some new, others already established, including:

- Toco y me voy: the immediate movement of the player following the release of the pass.

- Tabela: a player who wants to ‘toco y me voy’ needs a team-mate to ‘tabela’ with. Referred to in English as a ‘one-two’.

- Escadinha: forming diagonal lines to facilitate the movement of the ball from one place to the next, increasing in height.

- Corta luz: similar to a ‘dummy’ or a ‘feint’, using deception to fool a defender.

- Tilting: side orientation to the ball, approximating around it on one side.

- Defensive diagonal: a byproduct of tilting, an inward movement performed by the opposite side fullback to mark the opponent’s ball-far winger or simply close the inside space.

- The yo-yo: when an inside player receives the ball during a tilt, they turn back to where the ball came from and return the ball to the side of the original tilt.

Relationism vs positional play

Hamilton is careful to stress he isn’t claiming relationism to be the antithesis to positional play, rather another idea of a way to play.

“It was never designed as a dichotomy, or I never ever meant it like that,” he says.

“But the thing is, when you do, there is value in putting things in opposition, but just because they’re in opposition doesn’t mean it has to be black and white between those two things.

“For me, it’s more about the perceptual field of the players. That’s what I’m interested in primarily.

“What are the information sources that are being amplified, and which are being dampened? A mixing desk is the metaphor that I would probably use for that.

“A certain style of settings would be a more positional game, tweak them a little bit and you get more of a relational game. But there can be crossover, there can be cross pollinations, there can be hybrid systems, which is also a very interesting domain that’s come out of all this.

“But of course, to have a hybrid system, you need at least two distinctly different ingredients because you can’t actually mix things without difference.

“The whole public aspect of the discussion [about positional play and relationism] has been really interesting to me.”

Related Files

Coaching relationism

Hamilton says the question of how he coaches the style is the ‘million-dollar question’ and, by far, the most common one he gets.

While wary of positioning himself as a ‘guru’, Hamilton is keen to share more about the concept he has spent so much time researching, practising, developing, and experimenting with, and is clearly incredibly passionate about.

His ground for experimentation? The academy of Scottish Championship side Ayr United, where he coaches the under-16 boys’ team. It’s an environment where, Hamilton says, coaches are allowed to “develop and express themselves in their coaching”.

Hamilton’s Ayr United under-16s team displaying relationist principles in a game against Dundee

First things first, when working with his players, Hamilton doesn’t “use the terms positional play or relationism”.

Much like any other coaching style or approach, he simply builds his principles and what he believes into his practices.

He gives an example of a ‘starting block’: the pass and move (tabela).

“I used to do a 4v4+3 positional play exercise fairly regularly, or variations of them. It’s probably one of the most widely used exercises, I would say, among anyone who’s interested in positional play or possession football. We use these kinds of directional games.

“Of course, what you’re doing when you’re coaching that style of exercise, is you

say to your assistant coaches or your coaching team, you draw on the board in the office before you go out, you draw the dots where the players are, because you’re actually coaching a structure in that game.

“You’re not just coaching passing or receiving, but you’re coaching all those things within a structure, and you know the structure in your head before that exercise has started.

“If you do it with players who have never done it before, they run all over the place, and you tell them they need to understand space, they need to occupy the corners of the zone and so on.

“What you’re doing there is on the mixing desk, you’re really raising this idea of what distance am I from my teammate, what angle am I from my teammate, and that spatial aspect of the game and the player’s perception is at the forefront.

“It’s common to hear things like, from, let’s say, the Catalan school, people I’ve worked with, that the players go to their positions first, and they play from there, and then we relate, then we combine.

“Space is first, let’s occupy correct[ly], then let’s go and play. Those are your common references, this is the language that allows the players to interact.

“Take that away, now, what are you going to do? How are you going to achieve a kind of commonality?”

Enter: relationist principles.

“One way to do it, one of the first things I tried to do, and it’s something I actually still do, is use a directional possession game, but change the reference points,” Hamilton shares.

“So I’ll award a point for a successful one-two. It’s simple, so now the players are not necessarily thinking about, ‘oh, well, the ball carrier’s there, I should be positioned here, and my teammate’s over in the other corner, that’s good, we’re all set to make our triangles and progress the ball.’

“Rather, they’re thinking, ‘If I’m the ball carrier, where’s a teammate? If I’m not the ball carrier, is it a good moment for me to approach the ball carrier? Maybe I can catch them after they played that one-two. Maybe I can be the player who makes the next one-two.’

“You clearly get a lot of different dynamics happening, because players are immediately passing and moving, which is very different to teams that run a positional style. When you watch an exercise like these positional exercises, with these teams there aren’t that many pass-and-move actions.”

It is these pass-and-move actions that lead to what some call players ‘bunching together’ on one side of the pitch.

“Players bunching is one of the common aspects of this style of play but, interestingly, it’s not something I coach explicitly,” Hamilton explains.

“I’m not telling the players to bunch on the side, but because the players are attuned to perceptual references, such as give-and-goes where you need to be close, because it’s very difficult to complete give-and-goes across large distances, the tilting, or the bunching together is a result of the interactions that the players are looking for.

“In relationism, position of a function of the interactions and relationships between the players. So the position is actually secondary, rather than those more orthodox positional coaches that will put the position first.”

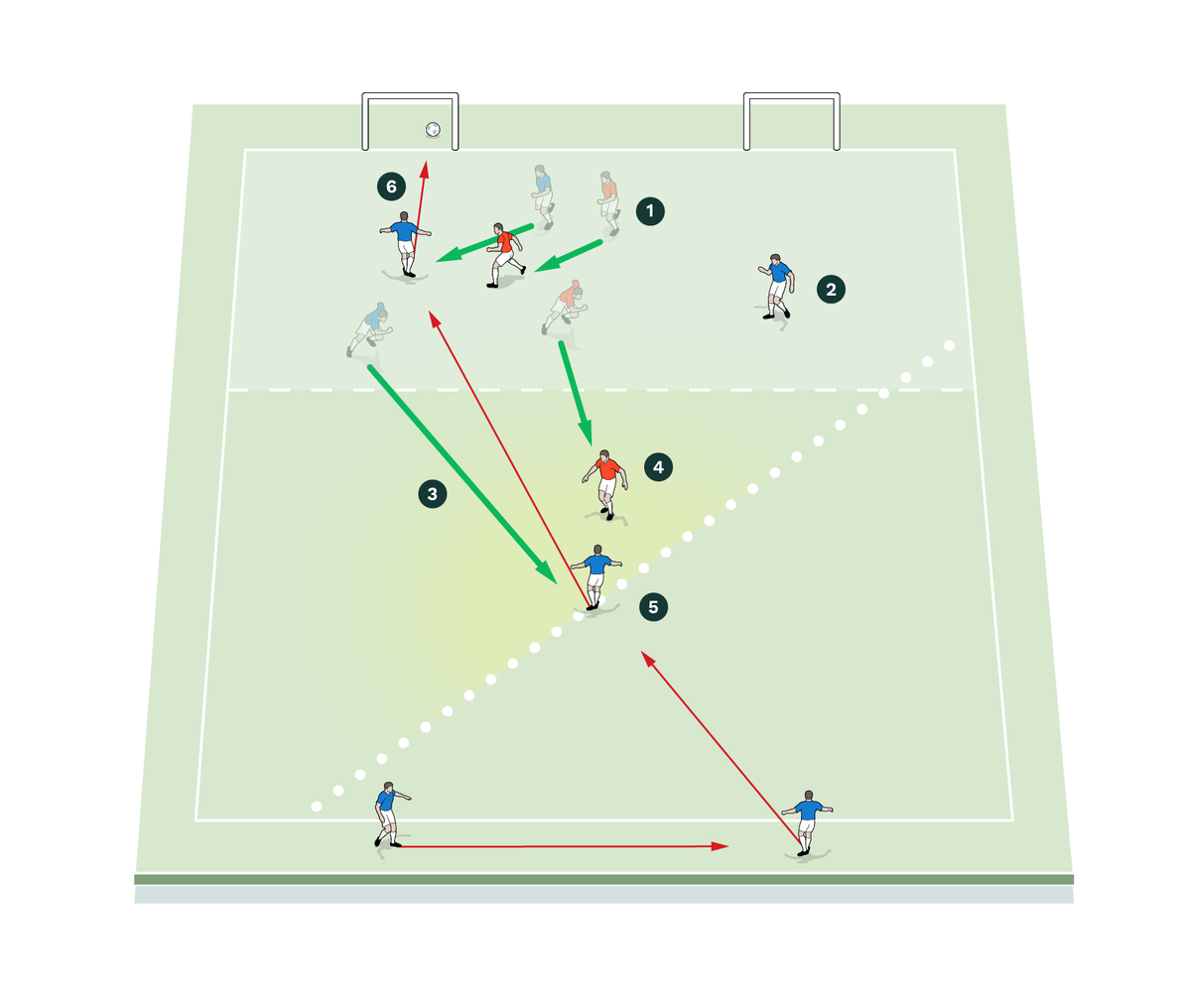

Another example Hamilton talks through is diagonals (escadinhas), making reference to two games he designed and uses. In the first practice (figure 1):

- A team of five and a team of two compete in a square area with two zones (the bottom slightly bigger than the top) and two mini goals

- The two defenders and three of the attackers start in the top zone, while two attackers are end players outside of the area

- Play starts with the outside players. One attacker must drop into the bottom zone to receive a pass from either end player, a defender must follow them as they do so

- The receiving attacker must outplay the defender 1v1 to progress the ball into the top zone, in which the attacking team can score in one of the mini goals

- Double points are given for a goal following a successful dummy, or a one-touch pass or flick connecting with an attacker outside the passer’s 180-degree field of vision.

Within this practice, Hamilton places emphasis on diagonality to increase the receiver’s field of connectivity.

[Figure 1]

- The defending team start in the top zone

- Three players from the attacking team start in the top zone, the two others are outside of the area

- An attacker drops into the bottom zone to receive the ball on a diagonal pass

- A defender follows the attacker

- The attacker outplays the defender 1v1, playing a shadow pass to a teammate who has made a run

- The attackers score a goal

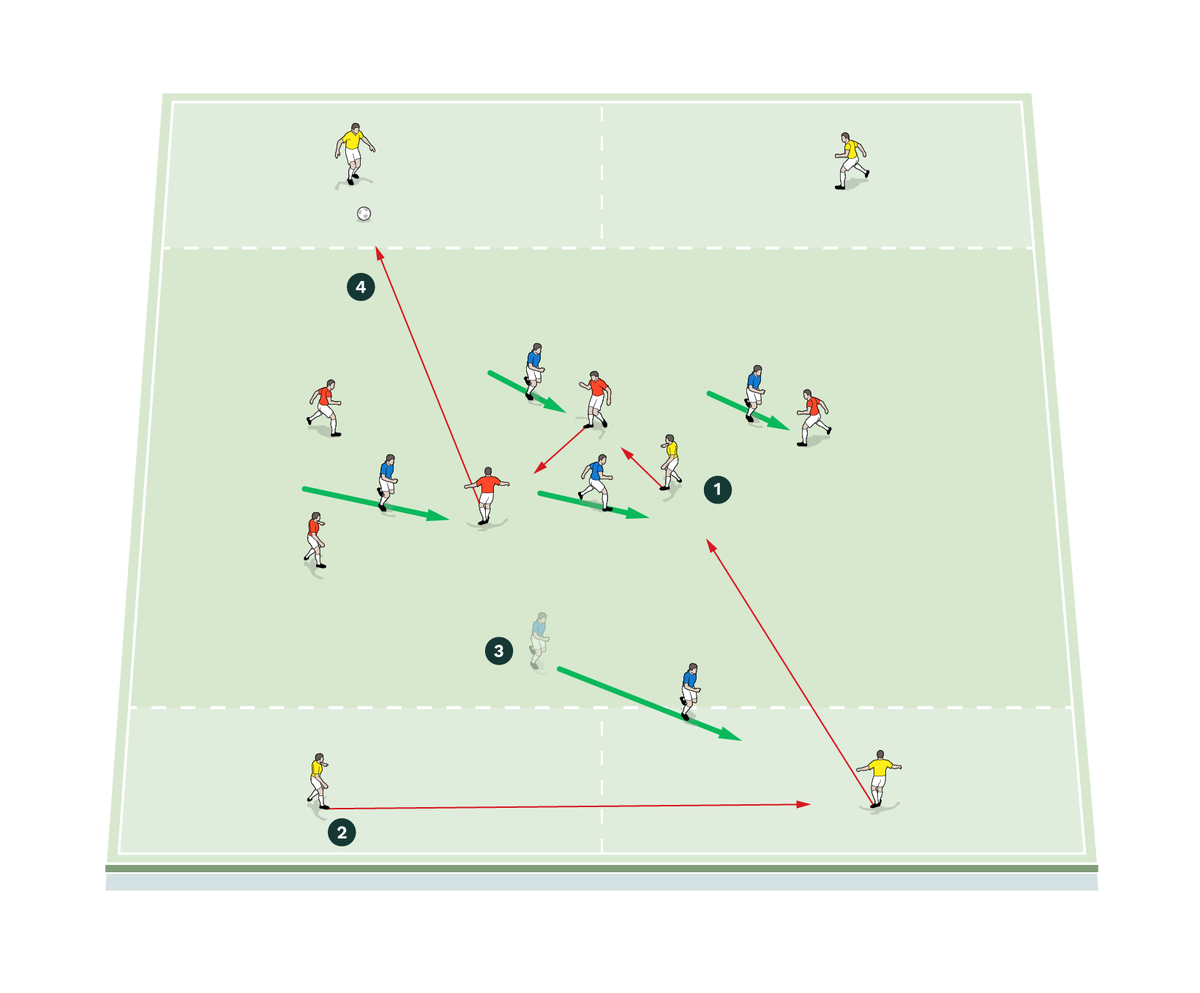

In the second practice (figure 2):

- Three teams of five are positioned in a square area with four corner zones

- Two teams compete 5v5 in the middle while the other team are jokers (magic players) with one player occupying each of the corner zones and one in the middle zone

- One defender is allowed in the corner zones to pressure the corner players

- A point is scored by completing a diagonal play from corner to corner with a maximum of three or four touches.

Within this practice, Hamilton places emphasis on:

- Diagonal perception of corner players

- The strength, angle and style of the diagonal pass to communicate possible actions to the receiver

- Orbiting the receiver

- Shadow passes, flicks and layoffs from the receiver

- Playing the diagonal pass immediately after a horizontal switch to go against the momentum of defenders.

[Figure 2]

- Two teams compete 5v5 in the middle zone while a joker team is spread out with one player in each part of the area

-

Play starts with a joker in a corner zone, the jokers play with the team in possession

-

A defender presses the joker on the ball

-

The attacking team combine with the central joker to complete a diagonal play from corner to corner

“These are very messy exercises,” Hamilton explains. “The players try and find patterns and they eventually emerge.

“You start to see that because of the diagonal orientation the players find themselves in all the time, they start to be able to do things like making dummies, which is very useful. For me, a dummy is not just a dummy. It’s not just an aesthetic thing. It’s very effective for training scanning.

“People talk about scanning all the time. Sometimes you see exercises like an unopposed passing drill and the coach is shouting ‘scan’. And you’re like, ‘Scan for what? A cone?’

“Scanning is not simply moving your neck. It’s interpreting information, and that information has meaning. If you want a player to interpret 360 degrees, incentivise actions that require 360 perception; a dummy requires 360 perception.

“If it’s incentivised, the player’s going to do it. And they’re going to become way better at seeing what’s all around them. And I don’t know if there’s many better things for a footballer to be able to do than know what’s all around them and to be able to interpret it.

“So again, this isn’t just, ‘Oh, I want them to make escadinhas,’ there’s a bigger purpose to all of this.”

Hamilton’s second escadinhas game in action with Ayr United under-16s

The future of relationism

While Hamilton continues to develop, refine and practise the idea of relationism from the southwest coast of Scotland, you could say somewhat of a relationist movement is growing across the game worldwide.

Professional teams that Hamilton has collaborated with include Malmö FF of the Allsvenskan (Sweden’s top tier), where head coach Henrik Rydström is, Hamilton says, somewhat of an ‘early adopter in the higher level professional game’ and Toulouse FC in France’s Ligue 1, where he was invited to give a presentation on relationism to the first team staff early last year.

Another team he’s collaborated with is Real Racing Club de Santander, who compete in the Spanish second league.

“If we’re looking for an example of club that this tactical paradigm or school of thinking is really adding a significant value to, then I think Santander is really interesting,” Hamilton says.

“There are 22 teams in the Segunda División. It’s a tough league. It’s got the vibe of the English Championship; a really long gruelling season, teams can beat everyone, a lot of strong teams.

“Santander have something like the 11th [biggest] budget in that league. They only came up a couple of years ago. They were in the fourth division not too long ago.

“Now they’re challenging for the title and promotion this year while playing – not all the time, but in many of the games when things go well and circumstances are good – some really, really nice football.”

Hamilton also makes reference to some Premier League teams that, he says, are “moving away from this more positional paradigm that has been quite dominant,” referencing some of the tactical evolutions the British game has seen in recent years.

“I think it’s interesting, because if you look back to the 2000s, early 2010s, Swansea City would probably be an example of a team who really leveraged positional advantages at a time when teams weren’t really able to defend that well against a positional team,” he says.

“It was new. It tracks with the Guardiola moment around 2009. The idea with the positional attack is you can locate occupy the spaces within the opponent’s block and use those spatial occupations to generate various advantages.

“A lot of teams weren’t able to defend that. They simply were like, ‘Oh, there’s a player between the lines… just leave them then because we don’t know how to defend them. How do we defend when there’s a player pinning us and their full-back can’t jump onto them?

“The defensive systems weren’t sophisticated enough to deal with very well implemented positional games. Someone like Swansea, who weren’t a big club in the Premier League, would destroy a lot of teams. They played really nice football.

“I don’t think you really get a team now of Swansea’s level in the Premier League getting that kind of advantage from playing positionally because all the coaches know how to play positionally and they all know how to defend it. So that kind of leverage, that niche, isn’t really there to exploit anymore.

“You hear people like Guardiola saying that defences have changed. Man-marking is something that comes up a lot. More teams are going more player-to-player or to more of a hybrid style where the players are free to go and pick up players between lines.

“Defensive systems in general, Bournemouth are a good example. Areola makes this kind of mixed pressing system, sometimes it’s zonal, sometimes it’s jumping into man to man.

“An orthodox positional structure game just isn’t going to have the same effect against that as it would have had against a classic 4-4-2 from back in 2011.

“I think that’s led to people thinking, ‘Okay, well, if these defensive systems are a little bit more sophisticated, a little bit more fluid, there are different avenues we can go down’

“One of the potential solutions is to say, ‘Okay, well, our players need to move around more because we’re being man-marked, we need to try and lose our markers.

“Of course, then the concern is if you allow your players to move around more, you lose organisation. And this is the big concern: you’re going to become a mess.

“How do the players communicate? What language are they speaking? If they’re all just moving away, moving around, what are the common references? How are they interpreting the game in a communal, cohesive way?

“I think that’s something that relationism addresses fairly directly. How are players cohering in a non-positional, non-zonal attack? How are they organized? Because it’s not a disorganised attack, it’s organized, but it’s organised in a different way.

“There are different references, different levels on the mixing desk are being amplified, different information sources are being interpreted.

“What are those information sources? How do the players achieve collective coherence?

“That’s something that is generally of interest to the coaches I speak to, because they’re up against these defences now and they need to be more fluid and more dynamic, but don’t want to sacrifice team cohesion.”

Again, it’s the mixing desk metaphor. What do you need to amplify? What do you need to tweak? How do you adjust your settings to get the outcome you need? Whether relationism is one setting, or the whole deck, it seems it is garnering interest and has a place in the game as it continues to develop.

Editor's Picks

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.