OUR BEST EVER OFFER - SAVE £100/$100

JOIN THE WORLD'S LEADING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME

- 12 months membership of Elite Soccer

- Print copy of Elite Player & Coach Development

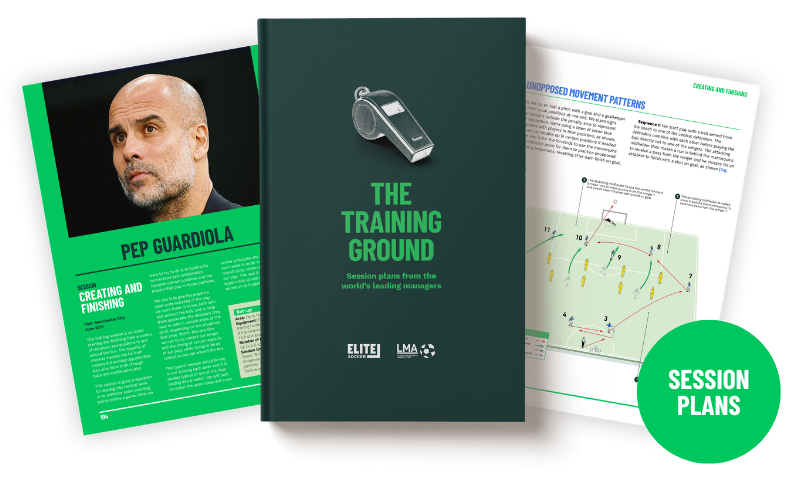

- Print copy of The Training Ground

You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Gareth Taylor: Where the magic happens

Gareth Taylor’s coaching journey so far has taken him from academy to Champions League. On a recent Elite Soccer Coaching Award webinar with Ben Bartlett, he shared his thoughts on everything from the transition from playing to coaching to the similarities and differences between the men’s and the women’s game.

Gareth Taylor’s career in football has taken him to the very top of the game – as a player, starring as an international for Wales, and as a coach, leading Manchester City in the UEFA Women’s Champions League.

But he also knows some of the game’s lowest points, having been released from Southampton as a youth player.

“The biggest thing I took from my playing career was how to deal with setbacks,” he says now.

He bounced back from that knock, signing for Bristol Rovers, before playing for teams including Crystal Palace, Sheffield United, Manchester City, Burnley, Nottingham Forest, Tranmere Rovers, Doncaster Rovers and finally Wrexham, working with coaches including Howard Kendall, Joe Royle and Steve Bruce.

Taylor arrived at Tranmere at the age of 32, and found himself in a squad with several other senior players who wanted to pursue their coaching badges.

“We knew that we couldn’t play forever, much as we’d like to,” he smiles.

That led to him eventually joining fellow Welsh international Dean Saunders as a player-coach at Wrexham, where he got the chance to work with various teams including the reserves.

After hanging up his boots, he returned to Manchester City, beginning with what he calls “a hybrid role” working across the boys’ academy age groups. However, he found himself on a sharp learning curve as he made the transition from player to full-time coach.

“I spent a lot of my time observing, and working with a lot of talented players,” he says. “Being a coach in that environment, I think it was priceless for me to have that experience with so many good people there.”

Initially working at Platt Lane before the new City Football Academy complex developed, Taylor was in a prime position to see the club’s progress to become one of the biggest entities in the global game.

“One of the biggest gamechangers for me at City was the St Bede’s project, putting all of the young players we had at various age groups into a private school. It allowed us to get access to the players every single day. You could just see we were stepping so far ahead of other clubs. It took a huge amount of investment and operations and a lot of work by a lot of people. You could really see a difference in our players.”

City’s game model at the time produced specific specialist players in some positions; Taylor highlights the midfielders such as Phil Foden and Cole Palmer. However, he also points to the fact that youth development is all about players’ individual pathways, and others may thrive with a different set-up – with Jeremie Frimpong a perfect example.

“All of our players were very good, but we had to identify the real performance players who were potentially of a high value in in various ways, and Jeremie was one that certainly was overlooked massively.

“When the big games came, he never wilted at all. He had so much energy on and off the pitch. [But] he wasn’t the fancied horse in the race, Jeremie, and no one really realised how good he could be. And before you know it, he was off playing for Celtic, doing really well, and goes on to become a top international.”

Taylor’s role was pivotal in supporting these young players at a crucial time in their youth career – the year the club made a decision on whether to retain or release them.

“When you got to Christmas time, you were doing your meetings with the players, and your squad effectively in the second half of the season just really broke up. You had lads who were going off on trial elsewhere, and City were really good, doing a lot of work to make sure that these lads who were being released had the necessary support to try and get a career elsewhere.

“You didn’t want these lads to lose any part of their development.”

Another challenge for Taylor working across these junior age groups was identifying how to use players who were still physically developing. Foden, he says, had the skillset of a central midfielder, but had been used on the wing as he was thought to be too small to play in the middle. Of course, Foden then went on a rapid rise to Pep Guardiola’s first team – where his versatility made him invaluable.

“Matchdays were tough for him, but even training days were tough because he was working with more physically developed players. He was the only player in my time there who skipped under 21s.”

Taylor took over as head coach of Manchester City Women in 2020, feeling he needed a slightly different challenge. He won a trophy in each of his first two seasons, winning the Women’s FA Cup followed by the Women’s League Cup (then the FA Women’s Continental Tyres League Cup), and narrowly missed out on the Women’s Super League trophy twice.

Related Files

The gap between girls’ academy football and the women’s first team was significant when Taylor took over; there was no equivalent to the boys’ St Bede’s project. It meant recruitment at all levels had to be considered carefully.

With the talent pool in the women’s game shallower than in the men’s, as the professional global game is in its infancy, Taylor needed to find recruitment tools for the best players.

“There’s certainly a lot of things that we did there that were attractive to bring players to the club, which would be our identity and our game model and the way we play and how we improve individuals. We did a lot of work in the in the IDP phase, preparing individual development plans for each player, and we used to use it as a recruitment tool as well. We weren’t saying that other teams weren’t doing that either, but we felt we put a lot of time and effort into that, and I had experience of running those programs in the boys’ academy.”

One of the issues in his final season in the role was a lengthening injury list, and he thinks that his experience in the academy game helped him develop his players and adapt to the constraints under which they were working.

“The situations overlap to a certain degree. You’re asking a player, as an example, a midfielder to go and play right back for you. [But] it’s not like we’re looking at you in this position because we’re looking at it for your future development. I’ve always kept development in my mind even as a first-team head coach because you’re always constantly looking to improve players on a daily basis to help the team.”

“I’ve always kept development in my mind even as a first-team head coach because you’re always constantly looking to improve players on a daily basis to help the team”

Taylor used a ‘what it takes to win’ model with the women, using the data to design a template, which also fed into the individual development plans. Of course, this approach also meant building a coaching staff that bought into the same principles.

“There were such big changes in the women’s game and Manchester City as an organisation. In the first season we had one physio and one sports scientist; this season, there were three sports scientists, three physios, a head of performance, which we didn’t have previously. We had enhanced analysis support, player care and welfare support. We had a specific person who would drive female athlete health. These are some of the things as a male head coach that you need to be aware of when you come into the women’s game.

“In most clubs, the performance team has grown, and what’s been neglected is the coaching staff. It’s important you don’t over-saturate them. The balance was good at City; they really built our performance staff and the support the girls had off the pitch.”

Taylor discovered that it was key to make his players feel part of the process.

“The biggest thing that I’ve taken over the last few years is understanding that they’re people, understanding that they all have motivators that drive them, they all need to be treated differently.”

That principle applies to male and female players – but he did notice a big difference between the boys and the women when it came to feedback in their analysis meetings.

“With the lads on analysis, they just wanted to know what you wanted them to do, and they’d go and do it. Feedback sessions were important as well. They didn’t want to see too much of the stuff that they did really well, they wanted to know what they didn’t do well, whereas the balance was really different with the girls. You had to sandwich it a little bit more.

“The lads were interactive, and you’d have some who were really keen on it as well, and they would be really eager to be the one to answer, whereas it was tumbleweed with the girls.”

It took some consultation with a sports psychologist for Taylor to understand and adjust his approach.

“The most powerful meetings we had were where we broke the girls off into groups of four or five. It was a hive of activity of feedback. Then when you asked them at the end for feedback, it was massive. When you feel like you’re involved in the process and you feel like you’re being heard, I think that’s when it’s just such a magical place to be in because everybody feels a lot more aligned to what you’re doing.”

Taylor says he has enjoyed a short break from the taxing “hamster-wheel” of being a head coach and all the support and input that requires. He’s also been reviewing his achievements at Manchester City, in the same way as he and his squads reviewed their training and their performances on a daily basis – a process that he says has been invaluable.

“There’s some real honesty in there from each other on what we could have done better. That’s going to help us so much going into what comes next. If you can gain as much clarity as you can, that’s going to help you and stop the frustration. There’s nothing worse than being frustrated on a daily basis as a head coach. The review process, for me, as I’ve got more experienced, is something that’s really helpful for me as a coach. How do you know if you’re improving or not if you never review?”

Editor's Picks

Attacking transitions

Deep runs in the final third

Using the goalkeeper in build-up play

Intensive boxes drill with goals

Penetrating the final third

Creating and finishing

My philosophy

Pressing initiation

Compact team movement

Coaches' Testimonials

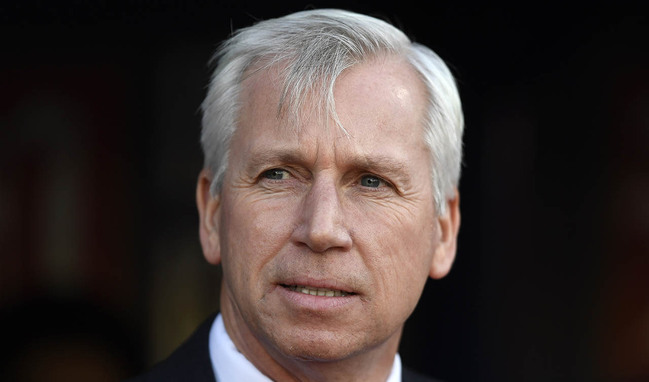

Alan Pardew

Arsène Wenger

Brendan Rodgers

Carlos Carvalhal

José Mourinho

Jürgen Klopp

Pep Guardiola

Roy Hodgson

Sir Alex Ferguson

Steven Gerrard

Coaches' Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Join the world's leading coaches and managers and discover for yourself one of the best kept secrets in coaching. No other training tool on the planet is written or read by the calibre of names you’ll find in Elite Soccer.

In a recent survey 92% of subscribers said Elite Soccer makes them more confident, 89% said it makes them a more effective coach and 91% said it makes them more inspired.

Get Monthly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Since 2010 Elite Soccer has given subscribers exclusive insight into the training ground practices of the world’s best coaches. Published in partnership with the League Managers Association we have unparalleled access to the leading lights in the English leagues, as well as a host of international managers.

Elite Soccer exclusively features sessions written by the coaches themselves. There are no observed sessions and no sessions “in the style of”, just first-hand advice delivered direct to you from the coach.